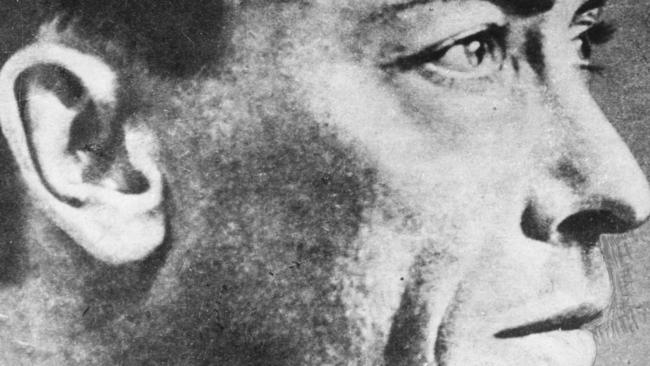

Colin Ross was hanged for the murder of a child, and pardoned 86 years too late

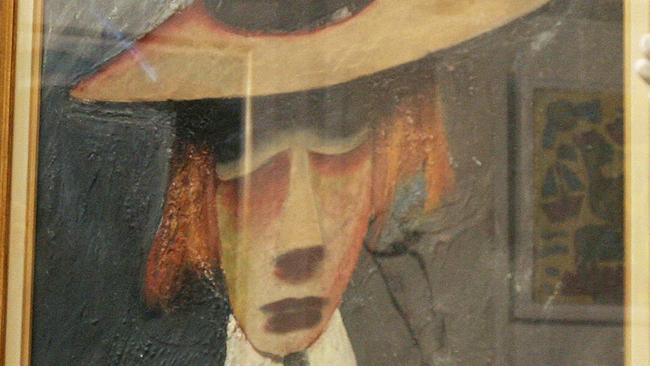

The gruesome murder of Melbourne schoolgirl Alma Tirtschke inspired a famous Charles Blackman painting series, but the man hanged for her death, was innocent.

Andrew Rule

Don't miss out on the headlines from Andrew Rule. Followed categories will be added to My News.

On the morning that Colin Campbell Ross was hanged in Melbourne 99 years ago, his lawyer stayed home and wept.

Thomas Brennan would never forget the monstrous injustice done to his client, or forgive those that had sent him to the gallows, wrongly convicted of a shocking crime.

Brennan started writing The Gun Alley Tragedy, a cool analysis of the evidence as compelling today as it was in 1922, about events that were equally tragic for two families — that of a murdered child and of the man accused of killing her.

For almost a century, the Brennan family believed that the legal establishment — to which they belong, ironically — effectively turned a blind eye to a monstrous injustice created by corrupt police, a baying public and a gullible jury.

Public opinion was as irrational as a lynch mob. Ross protested his innocence to the end, writing notes and marking passages in his prison bible. Failing justice, he needed a miracle, and didn’t get it.

Incredibly, the unthinkable got worse. The hangman put a faulty noose around Ross’s neck, condemning him to dangle and strangle, convulsing terribly, for up to 20 minutes.

It was an unspeakable end to an appalling chain of events that began four months earlier with the rape and murder of 12 year-old Alma Tirtschke.

Alma was a shy girl, small for her age but near the top of her Year 7 class at Hawthorn West Central school. She and her younger sister Viola lived with their grandmother because their parents had died several years earlier.

They were a respectable family. When Alma was asked to run an errand to the city for her Aunt Maie on December 30, 1921, she wore her pressed school uniform. She was to fetch a parcel from a Swanston St butcher.

She picked up the parcel at 1.30pm. Her aunt’s city apartment was barely a 10-minute walk away but for some reason Alma did not go there. She was seen dawdling near the entrance of the Eastern Arcade off Little Collins St more than an hour later.

It was no place for a child. If not actually part of the city’s red light district, it was close. In the arcade was a “fortune teller” run by the notorious and feared Russian woman who traded as “Madame Gurkha”. There were seedy shops and a bar — a dive named Australian Wine Saloon, managed by Colin Ross.

Reliable witnesses, none of whom were let testify at Ross’s later trial, saw Alma near the arcade entrance between 2.30 and 3pm.

May and Stanley Young saw her walk out of the arcade and cross Little Collins St to stand outside the Adam and Eve Hotel, a shady boarding house used by prostitutes. She looked wary, glancing behind as if scared of being followed.

Another passer-by, George Crilley, had earlier seen a man apparently following a girl matching Alma’s description. Crilley was about to intervene when the man seemed to move past the girl. But when he looked back, he saw she was talking to the man as if she knew him, clearly nervous.

Just after 3pm, a cab driver, Joseph Graham, heard a bloodcurdling scream near the Adam and Eve Hotel.

At dawn the next day, a bottle collector found Alma’s naked body in Gun Alley, a dead-end lane near where the Youngs had seen her. She had been strangled.

The crime inflamed huge public outrage, fanned by huge press coverage. Crowds gathered; many people left flowers.

The artist Charles Blackman wasn’t born until six years later but the lingering effect of the murder hung over Melbourne and later inspired his powerful series, the ‘schoolgirl’ paintings. And those, a lifetime later, would inspire a Melbourne researcher to take up the case to clear Colin Ross’s name.

Ross was arrested on January 12, two weeks after the murder. It seemed a convenient arrest to hose down public outrage and fears of a political backlash. Then, of course, there was the reward.

The state government at first put up a reward of £250, which was criticised as miserly until The Herald newspaper matched the amount. Within days, after The Argus criticised the government over its inadequate police force, the state boosted its reward to £1000.

The new total of £1250 was a life-changing sum for the time — enough to buy a good house or a couple of small ones. The lure of big money and the malign influence of certain police produced some strange “new” witnesses.

As proprietor of the “saloon” in the arcade, Ross was one of many people to be questioned. He willingly told police he had noticed the girl in the arcade because she stood out in the seedy area. His ability to describe her uniform accurately was held against him as “proof” he had plied her with alcohol in the saloon for three hours then raped and killed her.

Ross was no angel. He ran a rough bar and had come to police attention a few months earlier, when acquitted of charges of conspiring to rob a drunken customer. He had also been fined over a dispute with his girlfriend and for carrying a revolver, not a crime in 1921.

Worst of all, perhaps, his neighbour Madame Gurkha didn’t like him and his bar. But at age 28, Ross had no serious criminal “form”, certainly none of a sexual nature.

Ross’s problem was that he was close by when the police and their political masters were desperate to silence growing public and press criticism. Detectives arrested him and then, clearly, began shopping for witnesses to fit their theory.

They produced a convicted prostitute, a sacked barmaid with a grudge against Ross, and a career criminal who claimed Ross “confessed” to him in his holding cell.

These three, aided by the sinister Madame Gurkha, contrived a patchy story that ignored at least six more credible witnesses whose testimony showed that Ross hadn’t left the saloon all afternoon. Not to mention the taxi driver who’d heard screams just after 3pm — not at 6pm, the time when police claimed Ross killed the child.

The fix was in. Dodgy police witnesses apart, Ross was convicted mainly on the evidence of an “expert” Government chemist who tentatively agreed with the prosecution’s brazen assertion that hairs found on blankets from Ross’s bar matched hairs taken from the dead girl’s head.

Even by the crude scientific standards of the time, this was wrong. But no one would prove that beyond doubt until the end of the century.

The quiet hero of the story is a librarian, Kevin Morgan, the man inspired to research the case after viewing Blackman’s “schoolgirl” paintings in the early 1990s. The diligent Morgan won access to the court archives, and uncovered hair samples accidentally left in a dusty 73 year-old file.

In 1998, simple microscopic examination proved that the hairs used to convict Ross were not Alma Tirtschke’s. Ross should never have been convicted. Relatives of both families petitioned the State Government for a review of the evidence.

And so, in 2008, Ross was pardoned … 86 years too late.

As for the real killer? There is a candidate, but that is a story for another day.