Andrew Rule: Why is the Whiskey Au Go Go fire case still too hot to handle?

How high or wide the conspiracy surrounding one of Australia’s worst mass killings goes is still unknown. And certain old guard cops seem determined to keep it that way.

Andrew Rule

Don't miss out on the headlines from Andrew Rule. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Until a crazed cretin acting alone shot 35 people dead at Port Arthur for no reason in 1996, the worst mass killing in 20th Century Australia was in Queensland 23 years earlier.

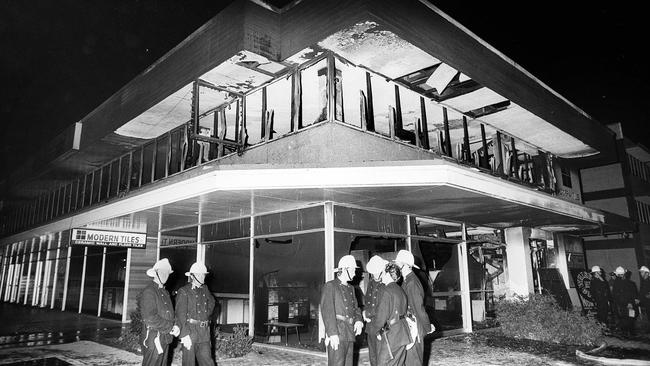

That was the Whiskey Au Go Go arson, when 15 innocent people died as fire exploded through the upper storey of a packed nightclub in the Brisbane suburb of Fortitude Valley.

The most evil thing about the crime was that it wasn’t committed by one insane person; it was a conspiracy fuelled by greed.

How high or wide that conspiracy went is still unknown, given the rats’ nest of police racketeering in Brisbane and Sydney at the time.

The Whiskey Au Go Go atrocity happened just after 2am on March 8, 1973, at the height of the corruption that flourished under the wilfully blind gaze of the Bjelke-Petersen government, later exposed in the Fitzgerald inquiry into the “Moonlight State.”

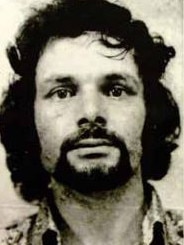

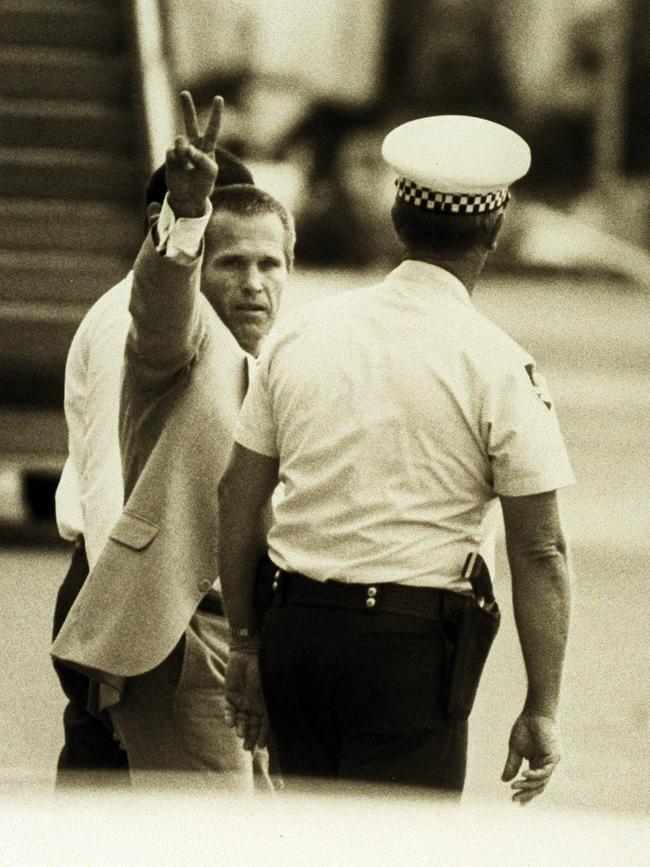

For decades, the firebombing was blamed on two criminals arrested within three days by the best police force money could buy — apart from their bent Sydney counterparts, that is. The embers, reeking of fuel, were barely cold when the police dragged in James Finch and John Andrew Stuart, violent men with bad records.

The erratic Stuart would die in Boggo Road jail in 1979 after several elaborate stunts, hunger strikes and self-harming done to publicise his assertion that he and Finch were “verballed” by investigators.

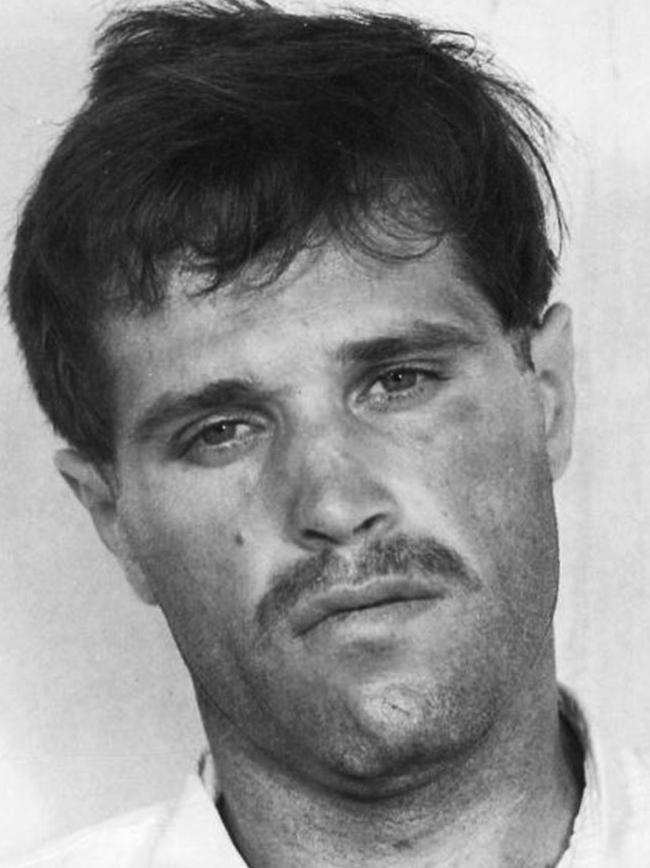

Finch, a less troublesome prisoner than Stuart, was known as the Birdman of Boggo Road because he was allowed to keep a pair of budgerigars in the exercise yard, where he trained by running around the tiny space for hours at a time.

The privilege of keeping birds was not the only favour granted to Finch, according to those who did jail time with him.

He was allowed to marry a wheelchair-bound woman while still in jail, and prisoner gossip was that the officers let the couple have sex in the prison dispensary. But once he’d used the marriage to help get parole, he treated the woman cruelly.

A former prison officer met the unfortunate woman later, and she told him how Finch would put her in a bath full of cold water to frighten her.

“He was a bad man, a psychopath,” he told me this week. “One of those prisoners who never laughed or cracked a joke.”

Finch was deported to Britain in 1988.

When an Australian film crew found him in a humble council house last year, he was just a pot-bellied old reptile with a dreadful past — and some secrets that have been buried with him.

Finch’s recent death has swung attention back to one of the worst crimes of Australia’s history.

The news that he had died earlier this year did not break in Australia until last week, when Queensland officials setting up a new investigation of the nightclub firebombing found that their potential star witness would now be silent forever.

No one has yet alleged that the wheels of justice were allowed to turn extra slow so that Finch would die before he could testify, but it’s only a matter of time before someone does.

The easy accusation that some Queensland authorities are in no hurry might not be correct but some critics will find it hard to resist.

For every honest young police officer trying to throw light on the scandal, there could still be older ones with skeletons they want to keep buried. Every old-time corrupt cop has “dirt” on others and so mouths stay shut and the silence continues. Or will it?

The relatives and friends of the dead already have a long list of questions and grievances over the peculiar handling of the case from the start.

It is true that Stuart and Finch were murderous criminals and that one or both were surely involved in the fire plot, in which men dressed in black were seen rolling two drums of fuel out of a car and emptying them into the nightclub foyer before lighting it.

But, for nearly five decades, sceptics have wondered if the pair’s swift arrest, trials and sentencing in 1973 conveniently blocked an inquest that year, shielding others from being implicated in a conspiracy that got out of hand, as fires so easily can.

The parallels between the Whiskey Au Go Go firebombing and the suspected arson of the Luna Park ghost train in Sydney in 1979 are striking.

Seven innocent people (six of them children) died in the ghost train fire, but the Sydney cover-up was so quickly co-ordinated that no-one was charged despite witnesses whose original statements clearly indicated arson — rather than the weak finding of “not sure but it wasn’t deliberate” made by a heroically uninterested coroner.

No coroner or police chief, even in Bjelke-Petersen’s Brisbane, could argue that the Whiskey nightclub fire was an accident. But who was in on it? Who stood to benefit from certain clubs being destroyed?

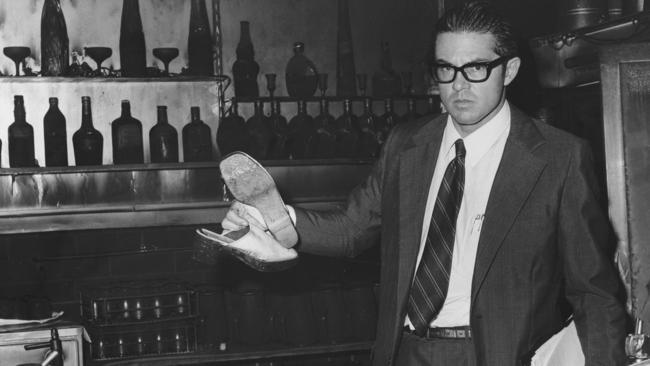

If it wasn’t Sydney club king Abe Saffron, an arson specialist, then why did his best bent cops Roger Rogerson and Noel Morey arrive in Brisbane the day after the fire?

The idea that Stuart and Finch were designated fall-guys hit the headlines three years ago.

That was when an old-but-deadly Brisbane criminal being sentenced for the ghastly murder of young mother Barbara McCulkin and her two school-age daughters drew attention by volunteering a denial so pointedly it put him squarely in the frame.

It happened in the Queensland Supreme Court on June 1, 2017 when convicted killer Vincent O’Dempsey, asked to make a statement before the judge passed sentence on him and co-accused Garry “Shorty” Dubois for the McCulkin killings of 1974, 10 months after the fire.

Anyone wanting to know all about this case should read the extraordinary book The Night Dragon, by our Brisbane newspaper colleague Matt Condon, who has peeled back the layers hiding O’Dempsey’s long life of cold-blooded murder.

Condon argues that Barbara McCulkin was silenced because she knew details about the nightclub fire from her husband Billy McCulkin, an associate of O’Dempsey. The daughters, aged 13 and 11, were collateral damage. That didn’t stop them being raped by the depraved killers.

A hush fell over the court as O’Dempsey made a statement claiming he was the victim of a “prejudicial smokescreen” implicating him in the Whiskey Au Go Go fire and the arson of another nightclub 10 days earlier.

He claimed he had nothing to do with either fire and had been convicted of the McCulkin murder on false testimony.

No one believed him. Worse, for O’Dempsey, his statement from the dock allowed the judge to release previously suppressed evidence from a fellow criminal who testified that O’Dempsey had boasted to him about his involvement in other crimes.

The day after the courtroom scene over O’Dempsey’s strange denial of the nightclub atrocity, Queensland’s Courier-Mail demanded the inquest be reopened. The editorial said: “While the truth behind the Whiskey has always remained blurred, this twist has the potential to rewrite our history and correct the past.”

Within hours, the state government announced the new inquest, which was entrusted to the clean hands of Det. Sen. Sgt Virginia Gray, who had worked with gun homicide detectives to crack the McCulkin cold case.

For those who’d got out alive that night in 1973, and for the families of the victims, the promised new inquest gave hope of justice at last.

But, after another four years, they are now entitled to wonder if the Whiskey fire is still too hot to handle and that someone, somewhere, would rather see the investigation fade away again.

Among the survivors of the fire are Kath Potter, Hunter Nicol and Donna Phillips, all prepared to testify at the new inquest. Their stories highlight striking parallels with the brazen suppression of evidence in the Luna Park fire in Sydney.

Shortly after the bombing, Kath Potter made a statement to police about what she’d witnessed from a nearby phone box just before the nightclub erupted in flame: she clearly saw three men get out of a black car and roll two fuel drums into the foyer of the building.

But, weeks later (she says), she was visited by police who had another story they wanted her to tell.

They produced her original statement. When she said “Yeah, that’s right” they told her that her statement was wrong and that she was lying.

As she later told reporter Condon: “I said, ‘I’m not lying. That’s exactly what I saw and I’ve told you what I saw and that’s what it is’.”

Potter says they continued to accuse her of lying and demanded she change her statement.

She is still troubled by the fact that the police were adamant only two suspects were in the frame, and by their insistence that she agree to make the change.

It is possible that a fresh inquest in each case, the Luna Park ghost fire and the Whiskey nightclub firebombing, will finally expose the truth about two crimes that are a stain on Australian society.

But you wouldn’t bet on it until it happens.