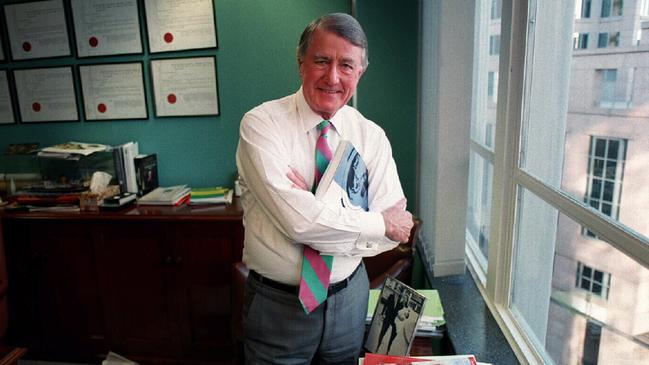

Former NSW premier Neville Wran was loved by many but he laid down with dirty dogs and lied

Former NSW premier Neville Wran orchestrated a closed circle of intrigue, influence, cronyism and veiled blackmail and knew how to milk the system.

Andrew Rule

Don't miss out on the headlines from Andrew Rule. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Lie down with dogs, you get fleas.

The late Neville Wran, much lauded former NSW premier, laid with and lied about some dirty dogs in his time. He picked up plenty of parasites – and a fortune that is hard to reconcile with an honest politician.

But the Teflon-coated politician, that the vice king Abe Saffron’s pet lawyer Morgan Ryan nicknamed “Nifty”, also raked in more than money and property.

He also gathered admirers: some being devoted groupies; others still with skin in the game.

Both groups stand to lose face if Nifty falls off his pedestal.

This was made clear last weekend when The Australian newspaper published a lengthy defence of Wran in response to mounting allegations he was linked through mutual friendships with the notorious Sydney crime boss, Abe Saffron.

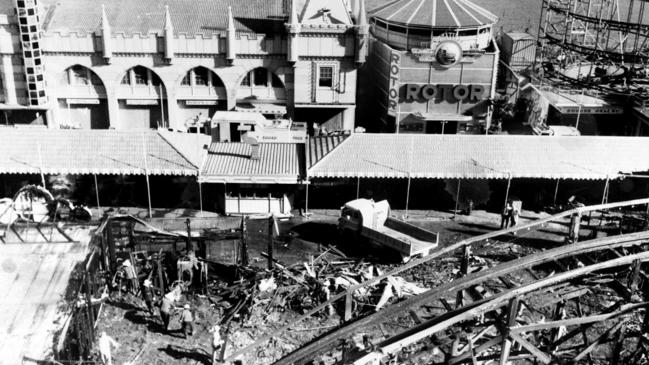

Saffron was named (not for the first time) as a prime arson suspect in a recent ABC documentary reinvestigating the tragic Sydney Luna Park ghost train fire that killed six children and one adult in 1979.

The ABC’s detailed and powerful case against Saffron and his links with Wran and other powerful figures follows several other stories published with the same theme since Saffron’s death in 2006.

I wrote one of those stories, a tough obituary, when Wran died in 2014 and so no longer protected by the lopsided defamation laws that choke fair comment and investigation in Australia.

A pro-Wran response has been a long time coming: almost seven years after that obituary and several weeks after a flurry of publicity sparked by the ABC series, Exposed: The Ghost Train Fire.

Time has not improved the argument in favour of Wran. Nor the writing.

First among equals in the Wran club is his executor, Malcolm Turnbull, who enjoyed a father-son relationship with the man who was friendly with his mother at university.

The failed prime minister’s fingerprints would seem to be all over the lame defence of Wran scrambled together in The Australian last weekend. It had all the finesse and judgment of Turnbull’s Godwin Grech debacle in 2009.

Hero worship has risks attached: if worshippers drop the rose-coloured glasses, heroes are mostly as flawed as the rest of us.

The reverse is also true: study a monster long enough and you’ll find some good points. Hitler was kind to dogs and small children and was a mesmerising public speaker but it’s hardly a reason to forgive the Third Reich’s atrocities.

Neville Wran was a hugely successful premier, still revered (mostly in Sydney) as a Labor hero after two “Wranslide elections” despite evidence suggesting he was as bent as a three-dollar note.

The rules say play the ball and not the man. Don’t sledge and punch: point to the scoreboard. But there’s a temptation here to do a Mark Latham and point to “the conga line of suckholes” that Wran defenders like to quote.

The retort to any of those clunky character references is: “They would say that, wouldn’t they?”

They have no choice but to boost Wran. Otherwise, it looks too much as if they were either in on the Wran rorts or too dumb to realise that shifty Nifty had fooled them along with the voters.

Any defence of Wran has to get past some extremely damaging own goals.

Wran was embarrassingly close to “Big Bill” Waterhouse, the ruthless and corrupt bookmaker and illegal gambling racketeer who did business with killers and robbers and standover men like Bert Kidd but also consorted with Sydney’s legal, political and business establishment.

Like Saffron, his contemporary crime king in Sydney, Waterhouse and his dodgy pub-owning family had been involved in the wartime black market, SP bookmaking, illegal gaming and receiving stolen goods.

Wran met Waterhouse at university in the mid-1940s and they became friends for life. Wran worked for Waterhouse at the races as a “runner”, making and collecting cash bets to square the book or to manipulate the market.

As a barrister in the 1960s and as a politician who rose to premier in 1976, and as a mysteriously successful “investor” after suddenly retiring from politics in 1986, Wran was always entwined with Waterhouse, who was at the centre of the three worst crimes in Australian racing history.

Waterhouse was behind the criminal nobbling of Big Philou minutes before the start of the 1969 Melbourne Cup.

Waterhouse was also involved in the “ring-in” race-fixing conspiracies that led to the murder of Sydney trainer George Brown in 1984, and to the closely-linked Fine Cotton ring-in scandal later the same year. He was outed for life over Fine Cotton with his son Robbie, although both managed to stare down the disgrace and connive their way back to the track.

Despite Waterhouse’s increasingly toxic reputation, the street smart Wran saw him as a useful ally. Shortly before the 1976 state election (in which Wran scraped up a one-seat win by a few dozen votes), Wran visited Waterhouse at his office at 158 Pacific Hwy, North Sydney. Also present were Bill’s son, David, then a teenager, and another bookmaker relative.

Wran asked Waterhouse for $5000 cash, big money at a time when a small suburban house brought $25,000. Waterhouse went to his upstairs safe and fetched ten bundles of $500 each and handed them over.

Wran did not say why he needed the cash to help his campaign or who was to get. But to solicit it from a man who ran SP books on the side and backed illegal casinos would be terminally compromising anywhere but in 1970s Sydney, arguably the most corrupt city in the English-speaking world since Prohibition Chicago.

Wran, of course, inherited Sin City from a Liberal premier regarded by all but eccentrics as the most brazenly corrupt politician in Australian history, Sir Robert Askin. To be fair, it’s a strong field, as it includes Brian Burke of WA Inc, Russ Hinze in the Moonlight State and Wran’s mafia-apologist mate, Al Grassby.

It was the sleazy Grassby that Wran helped in 1977 corruptly to let Italian-born gangster Domenico Barbaro back into Australia so he could join his murdering mafia mates in Griffith.

Wran’s toughest critics would not have considered him naive or foolish, even if some of his fans are. He was street-smart, savvy, charming, polished and applied his good looks and amateur actor flair to the way he sold himself and his government to a mostly malleable media.

It is inconceivable it was accidental or just bad luck that he appointed a notoriously corrupt cop, Bill Allen, ahead of huge field of more senior candidates, to be deputy police commissioner in 1981.

Allen, of course, had played a key (and sinister) role in the outrageous cover-up of the Luna Park fire in which seven innocents died. A cover-up that shielded not only Abe “Mr Sin” Saffron from being implicated but anyone else involved with Saffron in a long-range plan to develop the site – which was crown land controlled by the state government.

Allen was let retire from the force with his pension intact after Saffron blackmailed prosecuting barrister Roger Maxwell Court with a secret film of him indulging in sex with an underage youth. Allen’s sharp lawyer Philip Pollack was also, incidentally, Waterhouse’s lawyer for many years.

It was Allen who put another bent cop, Doug Knight, in charge of the Luna Park fire to ensure the crime scene was destroyed. And to sell the preposterous lie the fire had ignited from “electrical wiring” when the evidence was clearly otherwise.

Even a docile Sydney coroner would not swallow the “electrical wiring” story, which was allowed to die quietly once it had made the front page in the days after the tragedy. Not that the coroner could safely assert the obvious inference that the fire was suspicious, given that the evidence of arson was methodically sabotaged by puppet detectives under Allen’s direction.

Yet, staggeringly, Allen was earmarked as a desirable appointment. Two people are in the frame for influencing Wran on this: one is Wran’s confidant Bill Waterhouse; the other is Saffron, who had Allen on his bribery payroll. Saffron bought many police and politicians.

A now-retired Sydney businessman who knew Wran well socially and knew Saffron by sight told me this week he clearly recalls a small incident at the Bayswater Brasserie in Bayswater Rd, Kings Cross, shortly after Wran became premier.

The businessman noticed Saffron sitting alone at a table, as if waiting for someone. Then a large chauffeur-driven car pulled up outside and the familiar figure of Premier Wran stepped inside – but as soon as he glanced around, he spun on his heel and left.

What the businessman could not tell is if Wran saw Saffron and didn’t want the gangster to speak to him – or whether he recognised the businessman and didn’t want him to witness a meeting with Saffron. Either way, it was clear that the idea of being seen mixing publicly with Saffron spooked Premier Wran.

The same businessman also knew Wran’s first wife, Marcia, very well. Marcia Wran was a former Tivoli theatre “showgirl” whose fellow performers would have worked in Saffron’s glitzy clubs in Kings Cross, a scene she had frequented with Wran in their young days.

The businessman recalls visiting Marcia at home around the time Wran left her to take up with the much younger Jill Hickson. It was a time when the first cordless home telephones were being imported. Marcia showed the phone to the businessman but complained “it doesn’t work properly, like everything else Abe Saffron gives us.”

So the telephone was a gift from Saffron. It wasn’t worth much. But a connection to the rising political star was worth plenty to the gangster, whose bank manager had introduced him to Wran’s mate Bill Waterhouse. And whose crooked lawyer, Morgan Ryan, was the “little mate” of High Court judge (and former federal lawyer general) Lionel Murphy, Wran’s bosom buddy.

It was a closed circle of intrigue, influence, cronyism and veiled blackmail. But Saffron, the man who put the sin into Sin City, was not the only beneficiary.

Wran was good at sledging opponents from safe spots: at court, in parliament and from behind powerful allies. But he also knew how to milk the system.

The broadcaster Philip Adams tells of being approached by their mutual “mate” Kerry Packer to deliberately “defame” Wran in Packer’s magazine The Bulletin so Packer could safely pay him a cash “settlement”. A trick which bought many a politician or union leader a pool or tennis court – didn’t it, Bob Hawke?

The Balmain boy boxed more cleverly than his crooked Liberal predecessor, Askin. Like Askin, Wran insisted on being police minister as well as premier, and would later switch portfolios to include the one controlling mineral licences.

Like the grotesque Russell Hinze in Queensland, Nifty fancied being minister for anything with financial potential, but to “own” the notoriously corrupt police hierarchy was a goldmine because the routine tribute payments by SP bookies and illegal casinos flowed upwards.

As his old friend Bill Waterhouse said when Wran grabbed the police portfolio as well as the premier’s chair, “the police minister is the minister for corruption.”

That might explain why, when Wran died in 2014, besides a notionally modest estate, he left behind a web of property assets worth around $40m. We are supposed to believe he made it legitimately after retiring from politics at 60 and before he started losing his mind in his 70s. Go figure.

Shifty Askin, too, had started out poor and died very rich – although not quite as rich as Nifty. Funny about that.

But underneath the smooth façade, the spectre of the past worried Wran as he grew old. In his last interview, with a pet member of the fan club, he confided that when he died, people would continue to accuse him of corruption.

Towards the end, Wran was as haunted as his evil mate Morgan Ryan, who actually asked his executor not to publish death or funeral notices in case it led to more shame for his family. Ryan died in disgrace but left a $33m estate.

Wran loyalists might wonder why two men with links to Saffron were so worried about corruption allegations following them to the grave. Would anyone imagine that John Howard, for instance, is haunted by such thoughts?

The odds against that are a thousand to one and drifting.