Podcast companion: Another Walsh St suspect dead but it’s no loss

The anguished mother of murdered police officer Steven Tynan, killed in the Walsh St ambush, once said of the accused: “Everyone pays for their deeds and now time will tell. We think in a higher justice they will get what they deserved.” And based on the fates of the men accused of the crime, perhaps she was right. NEW PODCAST - LISTEN NOW.

It was the day after a big night and Damian Eyre had not long got home to his parents’ house in Shepparton, tired but happy.

He had been celebrating after being accepted into the police force.

His father Frank and older brother were in “the Job” and all the 18-year-old wanted to do was follow them into the uniform.

RELATED CONTENT:

LOCKWOOD ACQUITTAL: ONE LIFE TAKEN, ANOTHER RUINED

JANE THURGOOD-DOVE: MURDER BY MISTAKE?

PRUE BIRD’S DEATH AND RUSSELL ST BOMBER LINK

He was a wiry youngster in T-shirt and jeans, hardly more than a schoolboy but friendly and polite. He chatted with the reporter there to see his father about a notorious double murder committed 21 years before, in 1966. I was that reporter.

Frank Eyre recalled the night shift when he found the abandoned FJ Holden belonging to a local lad, Garry Heywood, who had gone missing from a concert with 16-year-old Abina Madill. It had been Frank’s job to break the bad news to anguished parents.

The abandoned car was the key to a crime that shook Australia. The teenagers’ bodies were found in a bush paddock two weeks later. It hid a fingerprint that would eventually betray the killer, Raymond Edmunds.

Frank Eyre could never have imagined he would be involved in another double murder that would resonate nationwide. But this time he and his wife would be the grief stricken ones, poleaxed by the news every parent dreads.

Only months after Damian left the police academy he and another young constable, Steven Tynan, were murdered in a crime of gut-wrenching savagery, revenge for the killing of a robber by detectives hours earlier.

The two young officers made easy targets, set up at random by killers who dumped a stolen car in the middle of a quiet street as a trap.

It happened at 4.47am on October 12, 1988, in South Yarra’s Walsh St, a name still freighted with grief and anger 30 years later.

Investigators concluded that five known offenders were directly involved in the shooting, although witnesses saw only four people fleeing the scene.

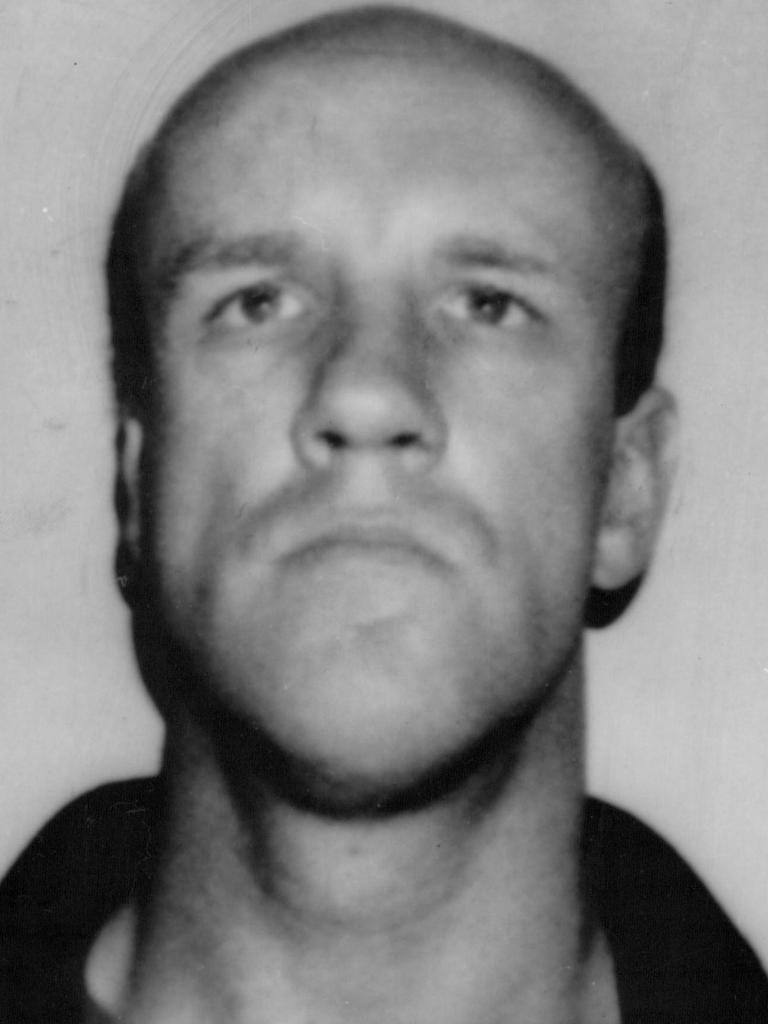

The presumed “fifth man” was as young as the murdered Damian Eyre. His name was Anthony Farrell. When he died this month of cancer after years of drug abuse and alcoholism, it raked up memories of the dirty war between callous career criminals and trigger-happy detectives.

At the time, police command vowed the killings would be treated like any other. But clearly this was not any other homicide: it was the first multiple murder of police since the Kelly Gang shot down three officers at Stringybark Creek in October 1878.

It was war, and Farrell and his teenage friend Jason Ryan were caught in the crossfire between their ruthless associates and “old school” police.

The 2009 film Animal Kingdom, inspired by Tom Noble’s book Walsh Street, captures the malice and treachery that led eventually to a huge murder trial that turned into a debacle.

At 20, Farrell was well-known to police, mostly for driving unlicensed, petty theft and the like. His father, Tony “Mushie” Farrell, had boxed under the ring name “Young Yank” but 13 pro bouts was as close as he got to steady work.

The old fighter was an underworld bit player and his namesake son was brought up breaking the law.

Anthony learned thieving and drug use and how to lie to police. His early criminal record suggests he always denied everything unless faced with overwhelming evidence.

After the Walsh St horror catapulted the underworld into a siege mounted by taskforce detectives, Farrell was seen as a “weak link” close to a core group of hardened suspects — Victor Peirce, Peter McEvoy, Jedd Houghton, Trevor Pettingill and Gary Abdallah.

Farrell was familiar with these serious criminals but he was young and (some former police think) not “hard” enough to commit premeditated murder, let alone be taken along by those who were.

Still, against the possibility Farrell was not present that night was the possibility that the older and more evil perpetrators like Peirce and McEvoy could manipulate youngsters like him along with provably violent bank robber Jedd Houghton.

Whether Farrell was at the murder scene or not, everyone associated with the case believes Houghton was, including his girlfriend’s father, who once told me Houghton was “used” by the gang leaders.

A stolen shotgun Houghton had used in armed robberies was the primary murder weapon. And he acted as if he was Australia’s most wanted man, fleeing Melbourne and arming himself with several handguns ready for a shootout with police.

It didn’t help him: Special Operations Group police shot Houghton dead in a caravan near Bendigo on November 17, five weeks after Walsh St.

Another suspect, Gary Abdallah, who’d reputedly supplied a getaway car, was shot by maverick detective Cliff Lockwood in a Carlton flat the following April.

Farrell’s role in all this is unclear. He clearly knew far more about the murders than an outsider would, but in his world such knowledge did not necessarily make him a killer.

Victor Peirce was widely held to be the Walsh St “organiser”. His claim to have been asleep in a Tullamarine motel with his wife Wendy that night was undermined when Wendy promised to testify against him and the others.

But Wendy “flipped” her keepers at the last minute and was declared a hostile witness. This crippled the prosecution case so badly that the jury was not sure that the case against the surviving accused — Peirce, McEvoy, Pettingill and Farrell — was beyond reasonable doubt.

Without Wendy’s collaboration, the prosecution case was reduced to relying on the evidence of Peirce and Pettingill’s unreliable nephew, Jason Ryan.

The trouble with Ryan, 17 at the time of the murders, was that he gave police several versions of the “facts”, even doing more than one re-enactment.

Without Wendy Peirce’s evidence, the effect of Jason Ryan’s changing story was to muddy the waters just enough to worry a jury. It might not have been a deliberate tactic, but it effectively sabotaged the police case.

On Tuesday March 26, 1991, after six days of deliberation and 895 days after the shootings, the jury returned a “Not Guilty” verdict. It was a victory for blind justice and the rule of law — and a massive blow to the police and prosecution.

Afterwards, the joint head of the Ty-Eyre taskforce, John Noonan, admitted “disbelief and total disappointment” and made the point that finding the four men not guilty did not make them innocent.

Damian Eyre’s parents did not attend court. Steven Tynan’s did. His anguished mother told reporters: “Everyone pays for their deeds and now time will tell. We think in a higher justice they will get what they deserved.” Perhaps she was right.

In 2002, Victor Peirce was shot dead at the wheel of a car, a casualty of the gangland war.

A shambling Peter McEvoy was last heard of in a NSW prison.

And now Anthony Farrell has died after years of self-destruction. No great loss.

As for Trevor Pettingill, he keeps a low profile.