Andrew Rule: Sinister duct tape clue in Kath Bergamin case

KATH Bergamin sacrificed her life for the sake of her three children, staying in a loveless and terrifying marriage. A decade after the coroner’s finding that she was abducted and unlawfully killed, an appalling silence still lingers over the contemptible crime. NEW PODCAST — LISTEN NOW.

Andrew Rule

Don't miss out on the headlines from Andrew Rule. Followed categories will be added to My News.

THE month before Kath Bergamin was abducted and killed, her estranged husband John and a shooting mate went to a Wangaratta store and warned a man there not to see her.

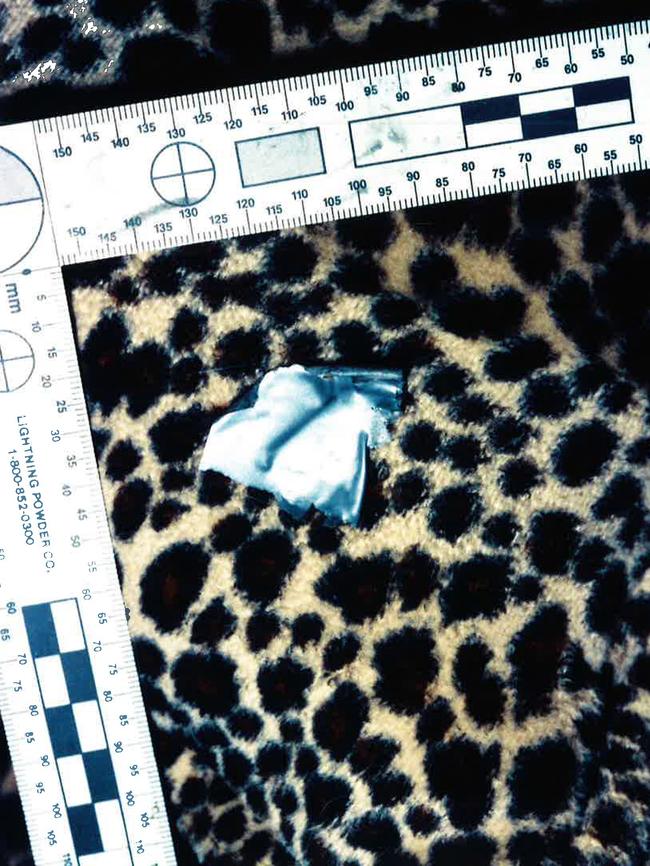

While in the store they bought a roll of Nitto brand silver duct tape that would become an intriguing part of a police investigation a few weeks later.

Ten days after Kath Bergamin disappeared from her rented house, police did a full search. They found silver duct tape similar to the Nitto roll sold to the shooters.

MORE ANDREW RULE: HOW THESE MELBOURNE CRIMINALS GOT THEIR NICKNAMES

STILL HAUNTED BY A LITTLE GIRL LOST

A small piece was in the living room. More sinister was the long piece rolled into two linked loops apparently used as bindings to tie wrists or ankles. This was lying outside as if lost in a struggle.

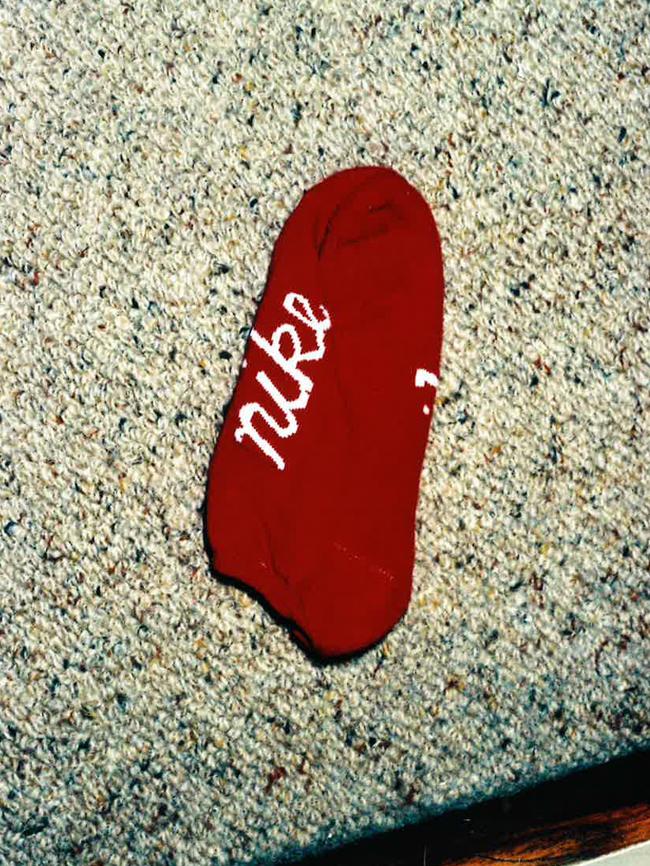

Stuck to the tape were red fibres of interest to forensic experts. The fibres matched red socks Kath Bergamin was wearing the night she vanished.

One red sock was found lying inside the house. The other, like its owner, was never seen again.

The ugly loops of duct tape are the best evidence police have. They look like a pair of nooses of the sort once used to hang murderers.

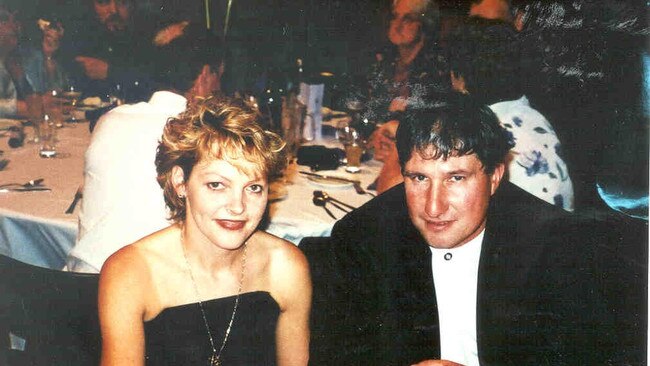

Kath Bergamin sacrificed her life for the sake of her three children, staying in a loveless and terrifying marriage nearly 20 years because she loved them. But when she disappeared that night in 2002, none of them wanted to know who had taken their mother.

They repeated a garbled story she had run away with another man or that she had been wanting a passport for “a holiday”. Neither was true. As became clear in the witness box at the inquest into their mother’s fate, they had nothing useful to add.

A decade after the coroner’s finding that Kath Bergamin was abducted and unlawfully killed, this appalling silence lingers over a contemptible crime that still causes stares and whispers between the King Valley and Wangaratta.

TRAPPED IN A SHOTGUN MARRIAGE

What was once Kelly country has become “chop chop” country where farmland nestles in ranges that the Kelly Gang roamed a century before a pretty schoolgirl named Kath Russell arrived in the district.

Within three years of her parents taking over a shop in the tiny town of Moyhu, Kath was trapped by a shotgun marriage that destroyed her self-worth long before she vanished, victim of a crime locals are still frightened to talk about.

Kath’s brother Roger Russell and her best friend Caroline Cuthbert and investigators probing her disappearance all remark on the sinister silence and wonder why her adult children studiously ignore what happened under their noses.

In the 1990s, some local police turned a blind eye to black market “chop chop” tobacco rackets. Mick Harvey wasn’t one of them.

The one-time drug squad detective manned the station at Whitfield in the King Valley and got to know the Bergamins at nearby Cheshunt. Many locals disliked John Bergamin and his older son Steven and Harvey saw why. He especially didn’t like the way they treated Kath. He sensed trouble, and made notes of his conversations with and about the Bergamins.

That precaution paid off when Harvey gave evidence at the inquest into Kath’s disappearance years later.

“I knew John Bergamin well,” Harvey recalls. “I was introduced to him by another cop and took a dislike to him. He was a standover man who tried to stand over me. Kath was a nice lady but she was petrified.”

Harvey confronted Bergamin over shooting protected wildlife. He also watchful with Steven Bergamin, 19 the year his mother disappeared. He says Steven was more intelligent and better educated than his father but had a disturbing attitude.

“Steven told me they had grand plans to get out of the tobacco business and branch out into a boutique winery. He was hell bent on it. Then he told me his mother was thinking of leaving ‘but she can’t because we’d lose half the farm’.”

When Harvey pointed out that it was her right to leave if she wanted, Steven retorted heatedly that they couldn’t “let her go”.

“I wrote that down after he left,” Harvey recalls. “It left me with an uneasy feeling.” So uneasy that when he got the D24 call in early 2002 saying there had been a shooting at the Bergamin farm, he assumed the worst.

He knew John Bergamin had a bad temper and an arsenal of guns so he asked for back-up to approach the farmhouse, in case of ambush.

When he and another officer got to the farmhouse, they found Kath bleeding from a head wound. She had attempted suicide with one of her husband’s rifles — shooting herself through the roof of the mouth and, miraculously, surviving.

Harvey held her hand until an ambulance arrived. His fears for her were mixed with his anger at Bergamin’s chilling behaviour at the scene: the farmer was more concerned for his guns than his wife.

“He was worried they (the authorities) would take his guns away.”

Harvey would later seize Bergamin’s guns after Kath got court orders against her husband to try to stop him stalking her when she finally got the nerve to leave the farm three months later.

But the policeman’s precaution did not save her. Only a decision to move to a secret location interstate might have done that — and Kath loved her children too much to go that far, despite the urging of her closest friend Caroline Cuthbert, who had moved to Adelaide years earlier. Caroline had feared for Kath’s safety ever since Kath confided she’d been told the only way she would leave the farm was “in a box”.

She did escape the farm in May 2002 but Wangaratta was no safe haven. She vanished on August 18, 2002, a Sunday evening. It was clear she had been abducted, although her mother, her brother Roger and her friends prayed their instincts were wrong.

As the 16th anniversary of Kath Bergamin’s disappearance passed last month, her husband and adult children still seem strangely uncurious about what happened to her. But other people are very interested — including detectives and experts working on sophisticated tests of the duct tape bindings.

CORONER’S BLEAK FINDING

NO matter how often he changes his name and works to distance himself from the evil forces that destroyed his mother, the smooth agribusiness marketing consultant now calling himself “Steven Zanin” can’t escape the coroner’s bleak finding she was unlawfully killed.

Neither can he duck the fact he and his father were excused from questioned at the inquest on grounds it might incriminate them. The coroner granted their application not to be examined about their police statements, which had internal inconsistencies.

John Bergamin and Steven have both denied being involved in Mrs Bergamin’s disappearance.

The Sunday Herald Sun is not suggesting they are guilty of murder, only that they were the subject of police investigations into Mrs Bergamin’s disappearance.

The coroner discounted the evidence of Bergamin’s shooting mate Pat Primerano and several other witnesses, including Steven’s brother and sister Renee and Dylan Bergamin.

It meant that lawyers could not quiz either John or Steven Bergamin about what a coroner accepted as the “torching” of Kath’s old Toyota Camry in a farm shed the morning after she vanished.

John Bergamin did not get asked why, when he telephoned ostensibly to find out where Kath was the morning after she disappeared, he did not call her mobile phone but her flatmate Sandie Riley’s phone. It struck Sandie then that he may have known Kath could not answer her phone.

As for Steven Zanin, the former Steven Bergamin adopted his grandmother’s family name after damaging publicity when he was charged in 2006 over a bizarre conspiracy to blow up a rival winery. He pleaded guilty to one count of incitement to commit criminal damage.

Police investigating Kath Bergamin’s abduction had picked up the alleged bombing conspiracy during surveillance. They were intrigued at the offer to pay someone to bomb the Gapsted winery near Myrtleford in retaliation for a price cut that would cost the Bergamin business around $90,000.

The “bomber” was offered $5000 expenses and a year’s wages to blow up Gapsted “lock, stock and barrel” and make it look like a terrorist attack.

Steven Bergamin allegedly said: “I want to be there when it happens … so I can watch it explode”. The plot was later abandoned but he was charged over the bomb conspiracy around the time his father was charged with murdering his mother.

The murder charges against John Bergamin were dropped in 2006. The prosecution decided not risk him beating the charges at trial. Instead, police pulled together evidence for the inquest, which took until 2008.

The coroner stopped short of spelling out what investigators and Kath Bergamin’s friends and her brother Roger have always believed: that whoever helped abduct her knew her.

They came for her after dark — between 7.26pm and 11.15pm. Only a few people would know she was home alone because her flatmate, Sandie, was working a late shift.

There was no sign of forced entry, suggesting Kath probably let abductors in because she knew them. Her address was hardly secret: Sandie Riley’s then boyfriend Pat Primerano was both friend and neighbour of John Bergamin.

Once the abductors were inside, it would have been easy enough to overpower her. But in the rush, they left those telltale pieces of duct tape.

Then, investigators believe, she was bundled into the boot of a car — most likely the anonymous Toyota Camry registered in Kath’s name, regularly used by Steven and often seen at the house.

Later, the coroner concluded, an unknown person killed Kath. Perhaps only one or two people know exactly how and where the body is buried or whether it was placed in remote bush for wild pigs and wild dogs to eat. But it is inevitable others know more than they have admitted so far.

One person haunted by inside knowledge has sent an anonymous letter containing inside information — a fact recently revealed by police to encourage the writer to step up.

Meanwhile, the letter writer faces the possibility someone else will get in first to strike a deal for indemnity. Anyone who knows the truth has a rare chance to unburden their conscience, clear themselves and have the killers arrested, all in one hit. And then collect the $1 million reward before someone else does.

Because the minute the scientific experts refine the DNA tests of the evidence, the reward will be off the table and everyone who can be charged will be charged, no matter who pulled the trigger.