Andrew Rule: Murder victim Salvatore Rotiroti’s family gagged by code of silence as potent as mafia’s

The strangest of many strange things in the murder of Salvatore Rotiroti — found beaten to death in his Geelong driveway — is that only one of the dead man’s extended family seems willing to find the killer.

Andrew Rule

Don't miss out on the headlines from Andrew Rule. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Keith Moor broke big stories in his time as a crime reporter for this newspaper. He once traced a mafia “supergrass” from Australia to his hide-out in Italy to ask him about the Donald Mackay murder for his outstanding book, Crims in Grass Castles.

But it’s a murder mystery closer to home that has tantalised Moor since he left full-time reporting in 2019.

This murder does not involve organised crime families like the Calabrian ’Ndrangheta. But it does involve a Calabrian family haunted by a devastating crime — and gagged by a code of silence as potent as the mafia’s omerta.

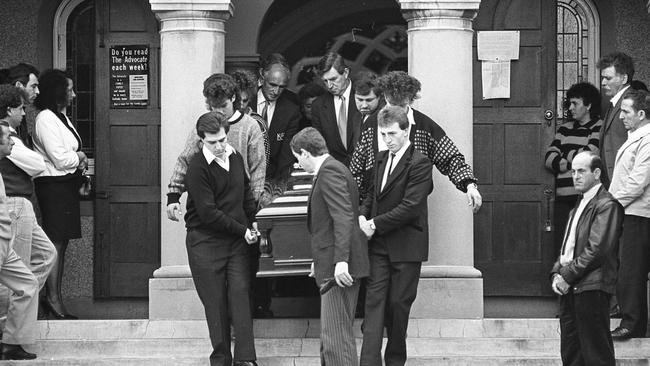

In 2018, on the 30th anniversary of the killing of Geelong concreter Salvatore “Sam” Rotiroti, Moor wrote a story detailing what had happened and breaking news of a million-dollar reward aimed at loosening lips.

Late on the night of September 5, 1988, Vince Rotiroti, then 22, returned home from visiting his future wife, Anna. He had stayed late, watching a film at Anna’s family house at Inverleigh, a chance decision he often ponders because of what might have happened if he’d got home earlier.

Around midnight his headlights lit up the drive of the Rotiroti house at 2 Purrumbete Ave, Manifold Heights. He instantly saw his father’s body in a pool of blood.

Sam, 46, had been beaten to death with a metal stake. Inside the house, Vince recalls, his mother and his older brother Joe, teenage brother Tony and two younger sisters were still awake, but none had checked why Sam had not come inside after opening the noisy garage door around 10.30pm.

Vince has never forgotten that detail. Nor that the back gate was unlocked. Nor that his mother told police she had sat on her bed and prayed that night. It was as if they were all frightened, he says.

Now, as the 35th anniversary of the Rotiroti murder approaches, police seem no closer to jailing the killer or killers than they were in 1988. Which is not their fault.

The strangest of many strange things in the Rotiroti murder is that only one of the dead man’s extended family seems willing to find the killer.

That lone crusader is Vince, who has never got over his father’s death.

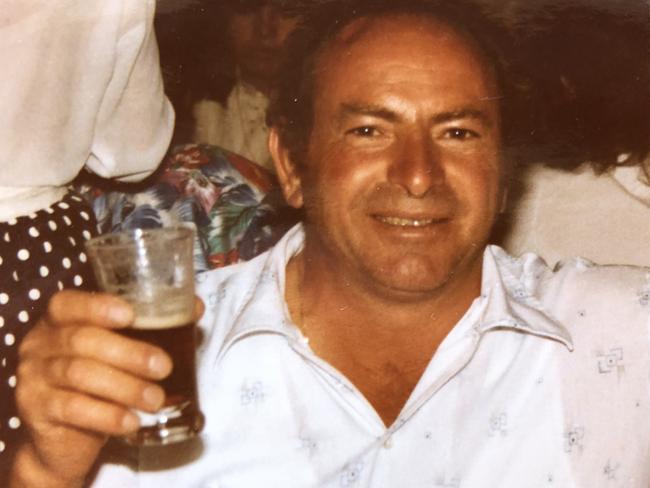

If anyone wonders if Sam Rotiroti somehow deserved to die, bringing it on himself with family violence, criminal behaviour or bad company: truth is, he didn’t.

In the months after the killing, detectives uncovered nothing suspicious about the hardworking contractor. The nearest he got to crime, it seems, was sharing a little homemade grappa with friends and sometimes working for cash in hand.

The father of five was quiet, well-behaved, and devoted to friends and family in the tightknit clan he’d married into.

His wife Giuseppina had two sisters also married to men from the same region of Calabria and the three lived close to each other in Geelong’s western suburbs.

Most homicide victims are killed by someone they know, often intimately. Investigators soon ruled out a random attack on Sam Rotiroti by a stranger or a dispute with an outsider.

From the start, they believed the killer was not only known to the victim but related by blood or marriage.

Nothing has changed that opinion in 35 years.

When Sam Rotiroti was killed, it seemed more of a shock than a surprise to his family. Dark, disturbing things had rocked the wider family circle for two years.

The week before the murder, two german shepherd dogs Sam kept to guard his trucks and work gear had vanished from the yard.

A back gate always kept locked had mysteriously been opened. Neither dog had got out before and neither was seen again.

Vince Rotiroti, who worked with his father, said then it must have been a family member who took the dogs. No one else could get the gate key — or safely get near the dogs.

Context makes the dogs’ disappearance sinister. Not only because of the murder a few days later but because of a shooting 16 months earlier.

Just before sunrise on the morning of May 13, 1987, Sam Rotiroti’s brother-in-law, Bruno Iannuzzi, was outside his back door when he was shot in the shoulder from behind.

He later told police: “I swung around and saw a male … about ten feet behind me wearing a multi-coloured jumper but I couldn’t see very well. I said something like ‘Why do you try to shoot me?’ but he didn’t reply.”

The shooter ran. Iannuzzi was at first fairly sure it was a close relative of his wife’s, a young man he initially named to police but later clammed up about.

Bruno Iannuzzi’s wife Teresa was a sister of Rotiroti’s wife Giuseppina; a third sister named Serafina was married to Dominic Zangari and also lived in Geelong.

The Rotirotis, Iannuzzis and Zangaris were big families who socialised and went to church together, as tightly connected as if they were hardscrabble peasants living in the Calabrian hills, generations earlier.

Although some of the Australian-born youngsters had grasped higher education and broader horizons, Sam’s migrant generation still obeyed the old world’s narrow religious and social customs — and held superstitious fears that opportunists could exploit.

According to Vince Rotiroti, his parents’ generation were targets for anyone who knew how to manipulate them.

A year before Bruno Iannuzzi was shot, the Iannuzzis and the Rotirotis started to get disturbing telephone calls from young-sounding males.

Sometimes, the caller would stay silent. Sometimes, he would make strange noises. Sometimes he would threaten to kill family members.

When Bruno Iannuzzi heard the calls he was sure he recognised the voice as his wife’s nephew, Vince Zangari. Bruno had known young Zangari all his life but had fallen out with him when he resisted Zangari’s efforts to persuade his cousins he had “special powers” to predict the future.

Bruno, like his brother-in-law Sam Rotiroti, didn’t like the fact that Vince Zangari held sway over their teenage daughters and often went into their bedrooms, supposedly to pray.

Sometimes, the nuisance caller was not Vince Zangari. It was another relative, one whose voice was also easily recognised. Both threatened sexual violence towards Bruno’s daughter.

Bruno knew Vince hung out with a pro boxer, Mirko Ecimovic, who lived in Geelong and would later be called as an inquest witness after making three contradictory statements to police.

Family members hardly needed proof to know who the nuisance callers were. But police and a coroner later heard that after the targets of the calls got silent numbers, the calls continued, proving the callers were family “insiders” with access to the new numbers.

To Bruno Iannuzzi, Zangari’s “tough guy” attitude was loaded with implied menace. A coroner would later hear that Zangari’s erratic and hostile behaviour had got worse after he’d suffered an injury at the Ford factory where he worked until 1986.

Meanwhile, Sam Rotiroti suffered not just ugly nuisance calls but extortion.

About a month before Rotiroti was murdered, he confided to Iannuzzis he’d been forced to pay $100,000 ransom to have his younger son Tony released from what he initially thought was a genuine abduction.

As a coroner would hear in evidence, Rotitori told Bruno Iannuzzi he’d also paid Vince Zangari $7000 to “fix” Tony after he had “gone crazy” but that he now believed two of his sons were part of a scheme to take money from him.

Police soon identified Vince Zangari, then 21, as the prime suspect for the murder and extortion. Within three weeks, they charged him with murder.

Zangari made five statements, each differing from the previous, as investigators picked up inconsistencies and falsehoods. His friend Ecimovic the boxer made three different statements regarding alibis for the time of the killing.

But what looked like a walkover for the homicide squad fell apart. Police were forced to drop the murder charge a year later because most witnesses who’d at first implicated Zangari now withdrew their statements, unwilling to testify. Police believed they were intimidated.

A car owned by Vince Rotiroti’s older brother Giuseppe (Joe) was firebombed in the family’s driveway five weeks after the murder. The family got menacing telephone calls and letters written in Italian. Someone wrote in crayon in the yard: “Your next Jaspepi.”

If it was a deliberate campaign, it worked.

In December 1989, Geelong coroner Ian Von Einem returned an open finding on the death of Sam Rotiroti.

The coroner noted that police had charged Vince Zangari with the murder, and that Zangari had “given an untruthful account of his whereabouts on the night of the murder.” Still, the charges had been dropped and there was “no direct evidence” to prove he was at the murder scene.

Zangari was entitled to stay silent to avoid incriminating himself. The coroner pointed out that he accepted the evidence of the victim’s second son, Vince Rotiroti, adding: “I am not convinced that other members of the deceased’s immediate family have been as honest and frank as this person (Vince) has been.”

Half a lifetime later, Vince Rotiroti still runs the Geelong concreting business his father started. He and his wife Anna and their daughters have made their own way.

Vince cut off his mother, brothers and sisters when they withdrew their statements. They, it seems, have stuck to the other Vince — the one they knew as Vince Zangari, but who has since changed his name nearly as often as his address.

Zangari first moved to Melbourne then to Sydney. His cousins Maria and Giuseppe (Joe) Rotiroti, adult children of the murdered man, followed. They, too, have changed their names.

It appears, curiously, that the three live together in an expensive Sydney suburb, and regularly attend a local Catholic church, where they are popular with older, Italian-speaking parishioners.

Meanwhile, Victoria’s cold-case investigators are waiting for someone to cash the million-dollar reward for naming Sam Rotiroti’s killer. Keith Moor will make a comeback to write the exclusive story.