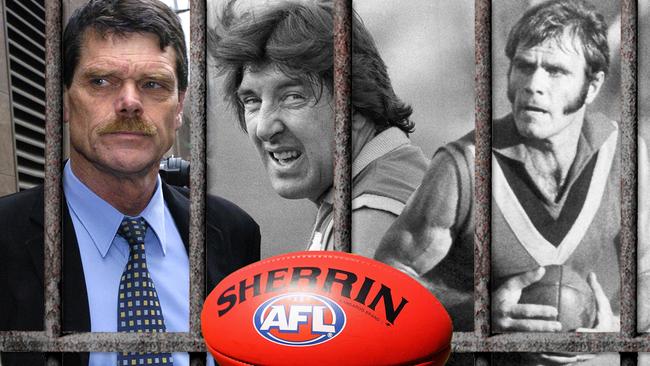

Andrew Rule: When star footballers turn bad

Aussie Rules attracts people from every level of society, so it’s hardly surprising that among the hundreds of players at the top level there have been some serious rogues.

Andrew Rule

Don't miss out on the headlines from Andrew Rule. Followed categories will be added to My News.

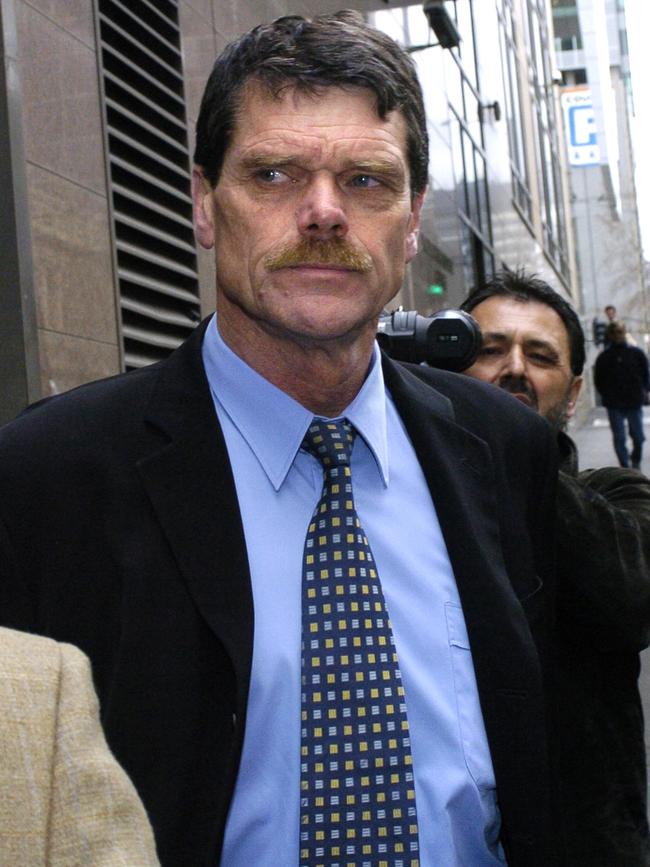

In the split second it took his killer to pull the trigger, Robert “Jack” Richardson must have realised the truth: every wrong turn in the long and winding road since the sweaty glory of his playing days had brought him to this.

The former footballer had turned into a crook and crooks always think the bad ending is for someone else, right up until it isn’t. For the sometime ruckman, it ended with a bullet in the brain beside a bush backroad in a bermuda triangle of unmarked graves and unsolved homicides an hour north of Melbourne.

Forty years later, the old footballer’s death is still a blot on the homicide squad’s records. A new generation of detectives know Richardson was in a St Kilda ice cream shop late at night with two men he apparently trusted.

The word was out back then that Richardson’s co-offender Alan Williams was a dead man walking, that bent cops from Sydney wanted him killed.

It all tied in with the botched execution of undercover policeman Michael Drury at his kitchen sink in Sydney’s Chatswood in June, 1984. And the subsequent disappearance, as in abduction-murder, of the presumed Drury trigger man, Christopher Dale Flannery. This was a crew who killed witnesses, and corrupt police were up to their Rolex watches in it.

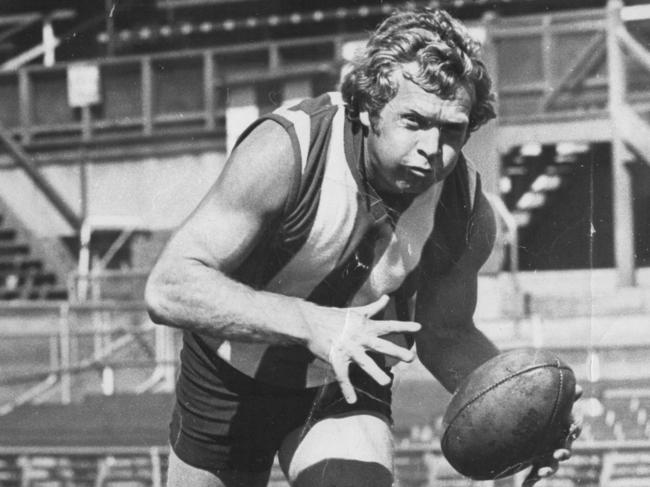

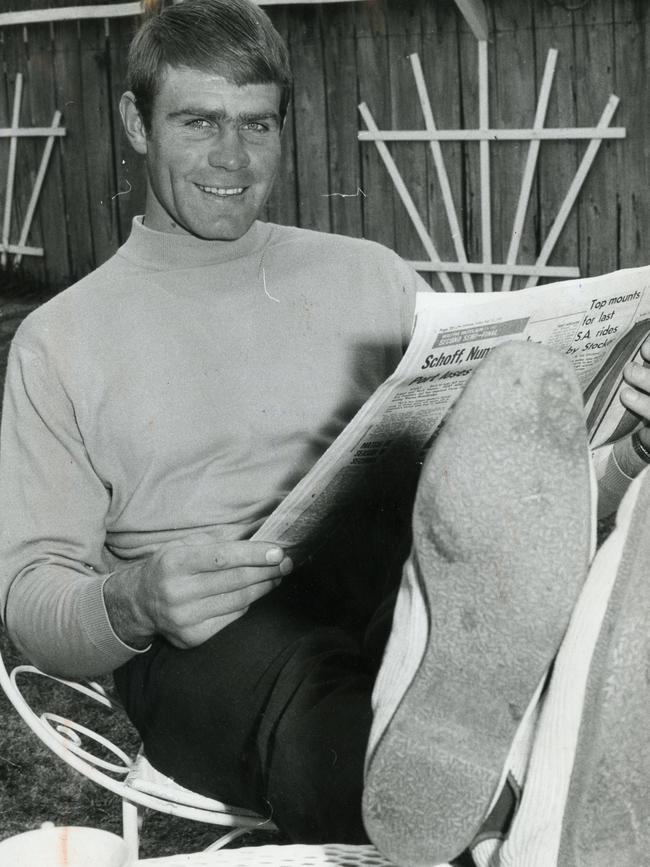

At 49, Richardson was the father of a young daughter, and son of parents who had set him on his journey through junior sport to professional footy. He played 103 games as a ruckman with West Adelaide in the SANFL before he became a player in a more dangerous game.

Once he’d hung up the boots, Richardson moved to Melbourne and ended up in the notorious Federated Painters and Dockers Union, which in the 1970s effectively ran the underworld from the waterfront.

As a “dockie”, Richardson moved in heavy criminal circles and eventually linked up with a crew that imported the big money maker, heroin, through the docks. His ties with another heroin trafficker, Alan Williams, proved fatal.

Both men were due to testify in a trafficking case, which might have implicated bent police in drug rackets and other crimes. So there was a price on their heads.

The desperate Williams dodged the killers and the cops, though not the effects of his own addiction. Richardson the lumbering ex-ruckman was less nimble.

He was spotted by an off-duty policeman in an ice cream shop in St Kilda between 1.20am and 2am on the morning of the day he disappeared, August 4, 1984. He was due in court the next day but never seen alive again.

Four weeks later, two fishermen found his body beside King Parrot Creek Rd in the farming district of Strath Creek.

The killing stayed dormant for 39 years. Then, last month, investigators combing old cases for clues announced they now have a DNA sample from the crime scene that could identify the killer. They have dangled a $1m reward to tempt someone to blow the whistle.

Jack Richardson is just one “dirty player” who switched from football to crime.

Regardless of what cynics say about racing and boxing, no single sport has a mortgage on criminality.

A feature of Australian Rules is that it attracts people from every level of society, and has always been a stepping stone for knockabouts to match all comers. It’s hardly surprising that among the hundreds of players at the top level there have been some serious rogues.

Not all get caught. For every bit of scuttlebutt about this former star stealing tyres and that one nicking his teammates’ golf clubs to pawn, and a dominating finals player robbing friends to buy drugs, there are people who get away with much more.

Such as, for instance, the budding businessman known to keep a pistol in his pants in the change rooms of North Melbourne’s Arden St ground.

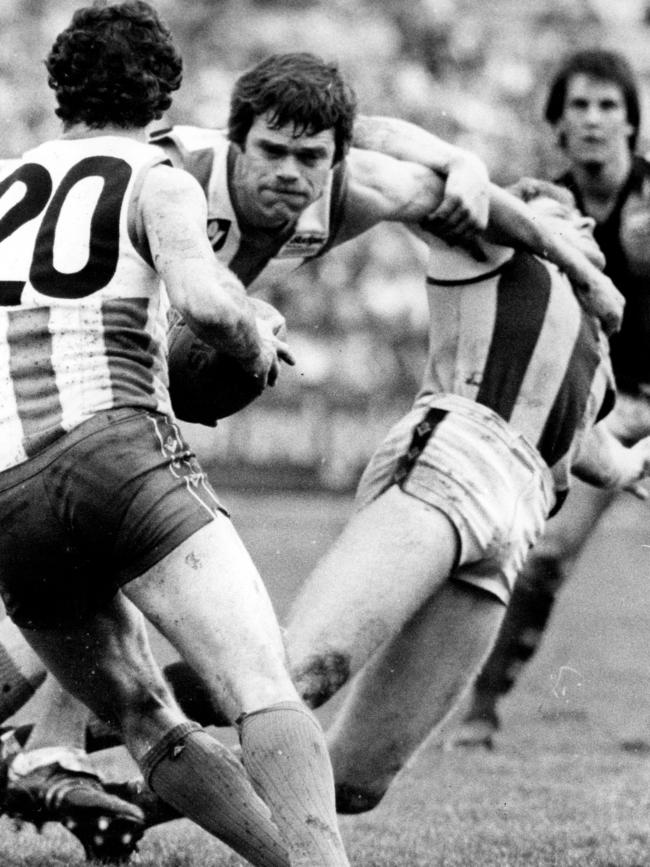

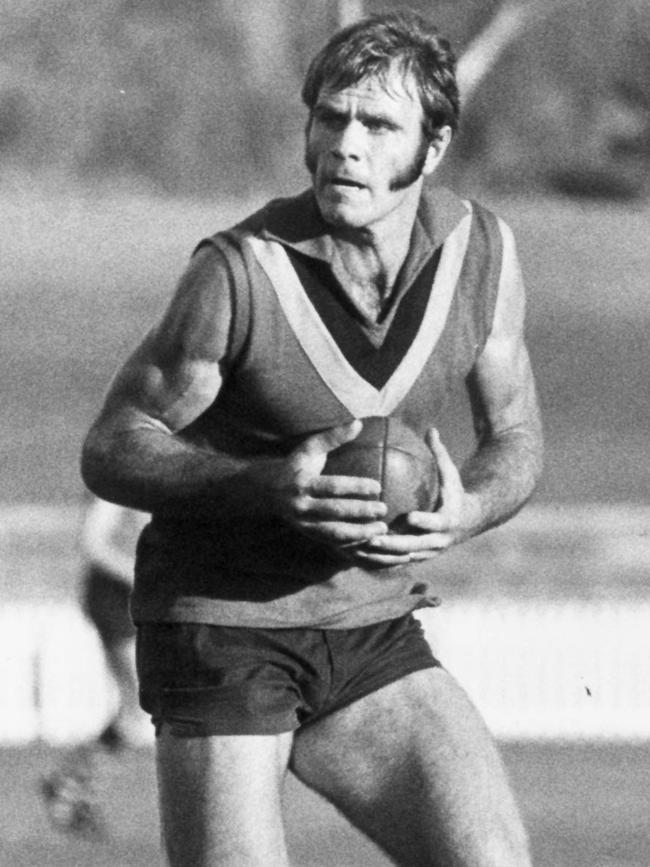

The player with the pistol dummied around the law and became a property millionaire. Not so lucky was another Kangaroos stalwart, famed fullback David Dench, who was lured into a fraud racket by a cunning racing identity named John Capellin.

It ended badly for all concerned, especially for the education system and taxpayers ripped off for tens of millions of dollars.

Dench, Capellin and others went to jail in 2008, convicted of fraud and bribery over the huge scam centred on Victoria University.

Capellin, then a prominent racehorse owner (with the star galloper Testa Rossa), set up the rort at least four years before Dench came along in 1999. Capellin and his cronies were syphoning huge amounts of money from Victoria University for maintenance work not done, using a complex web of false invoices and receipts approved by corrupt university staff. The conspiracy reached high into the university’s administration.

Capellin’s web snared Dench and led to a total of 20 people being charged over what a prosecutor described as “pigs at the trough making themselves sick at the expense of the university.”

Dench would serve only a few months in jail, but the fall from grace was crushing for a champion who had captained his club at 21, led a premiership team in 1977, and was honoured in the Australian Football Hall of Fame.

Ironically, the coach who sacked Dench from the senior side in 1984, Barry Cable, has ended up in deeper disgrace than Dench.

Cable, fabled 1960s and 1970s rover, has been stripped of football awards after being named, blamed and shamed by a judge in a civil action for repeated sexual abuse of a young teenage girl in the 1960s.

The victim was notionally awarded more than $800,000 but the cagey old rover slipped the tackle, declaring himself bankrupt. Cable hasn’t been charged with a criminal offence but he’s a pariah in the game that defined him.

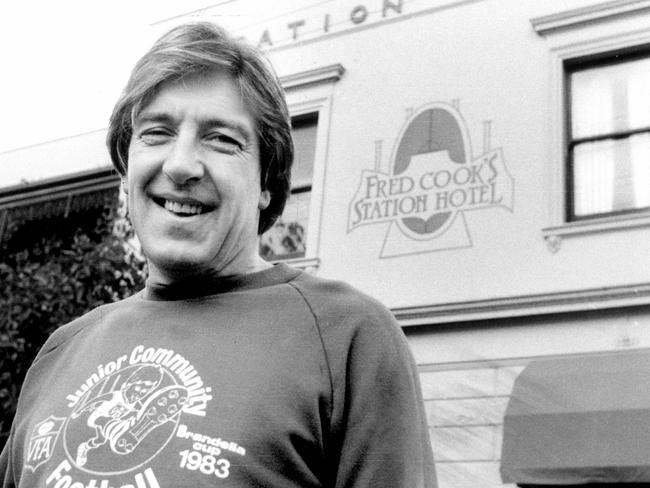

There are those, like Richardson, who pay a terrible price because of their addiction to easy money and bad company. Fred Cook was lucky to die in bed last year at 74 after a life of living dangerously.

Cook, who switched from Footscray to become the most prodigious VFA goalkicker of all time, scored heavily in all ways. Apart from a record 300 VFA games (plus 33 with the Bulldogs), he kicked 1300 goals and fathered “11 or 12” children with a number of wives and partners.

Although essentially harmless, Cook hung with violent crooks and became a slave to amphetamines, which led to crimes of dishonesty and three spells in jail.

Others dodged jail. A former Carlton and Richmond heavyweight, a victim of “the punt”, got away with pulling on a balaclava and robbing an SP bookmaker near Flemington. Everyone there knew the armed man behind the mask but politely pretended not to.

That old rogue is still out there, an honorary associate of the “Carlton crew” occasionally seen at underworld funerals. He was a fearless player and a fearless punter who never ducked a drink, a bet or a fight.

We won’t name him because he was never convicted of anything serious. But one of his contemporaries, also with a celebrated football surname, wasn’t so lucky.

His name is Dean Lynton Ottens, a South Australian state player in his own right — and father of Geelong triple premiership star Brad Ottens, who also played 129 games for Richmond after crossing from Glenelg in 1998.

It is 30 years this month since police and National Crime Authority officers gathered to raid a huge (10,553 plant) cannabis crop on remote Hidden Valley cattle station in the Northern Territory.

The raid followed months of investigation, and crushed a conspiracy between members of the Calabrian organised crime group ’Ndrangheta and Dean Ottens, who owned the station.

The Calabrian conspirators, mostly from Adelaide, had approached Ottens because he was in financial trouble. The mafiosi baited a hook for the footballer-turned-cattleman: if he provided a patch of land near a bore to grow cannabis, he’d get one eighth of the profits.

Ottens’ wife had left. Their young teenage son, Brad, had to leave boarding school to help work the property. Prices were low and costs high and Ottens couldn’t meet payments on $700,000 debt. He gambled that the mob could pull off a big crop that might help save the business.

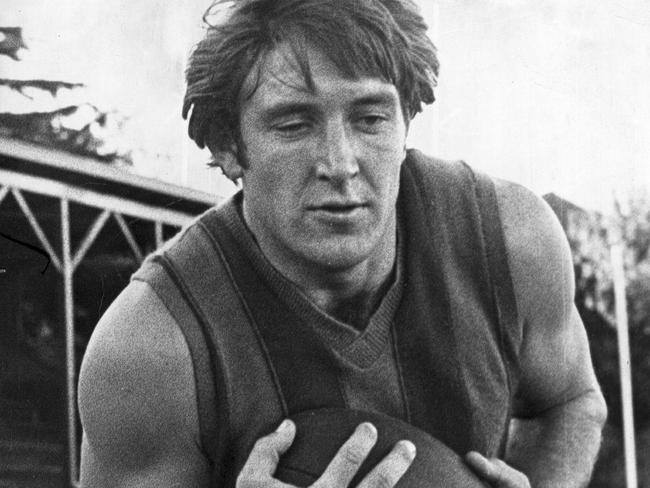

As a player with Sturt, Dean Ottens had been renowned for toughness, playing for South Australia seven times before going north to try his hand in the beef game.

The NCA and police had been monitoring the cannabis conspiracy for months. Investigators knew that the Adelaide-based Perre mafia family was behind it, notably Dominic Perre and his brother Frank.

Dominic’s uncle, Antonio Perre, had arrived from Italy on a visitors’ visa in early August, 1993, going straight to Hidden Valley from Darwin. Antonio, a convicted murderer, was a senior ’Ndrangeta man. When he was arrested at the station later that month with 10 others, including Ottens, his nephew took it badly.

Dominic Perre would end up beating the cannabis crop conspiracy charges himself, but he never forgave the NCA investigators for humiliating him, his family and the “Honoured Society.”

The target of Perre’s hatred was Det. Sgt. Geoffrey Bowen, seconded to Adelaide to investigate the Calabrians.

The Hidden Valley arrests angered the volatile Perre. He was incensed after Bowen’s investigators trashed his house during a search, leaving pornographic videos (found in a drawer) on a bed to embarrass him.

Grievances festered when Perre family members in custody were not allowed to attend Dominic’s mother’s funeral.

These events led to one of the worst crimes in Australian history: the bombing of the NCA building on March 2, 1994.

When Geoffrey Bowen picked up a parcel he joked it could be a bomb but opened it. The explosion killed the father-of-two, permanently injured his workmate, lawyer Peter Wallis, and showered central Adelaide in broken glass and debris. It was Bowen’s ninth wedding anniversary. He was 36.

The bombing was clearly Dominic Perre’s work, although it would take almost 30 years to convict him. He died in custody early this year.

Dean Ottens had absolutely nothing to do with the bombing. He was sentenced soon after to seven years with a minimum of two-and-a half for the cannabis charges.

Despite the trauma of his teenage years, or perhaps because of it, Dean’s son Brad helped keep the station going. He became one of the finest South Australian footballers ever to play the game. A deocrated champion of the AFL, Brad Ottens was not involved in any of the crimes of his father and has never been accused of wrongdoing.