Andrew Rule: Lives, money saved if police use specialist tracking dogs for missing persons’ cases

Scent hounds are phenomenal trailing machines used to great effect in the US to find missing people and save lives. So why aren’t they here?

Andrew Rule

Don't miss out on the headlines from Andrew Rule. Followed categories will be added to My News.

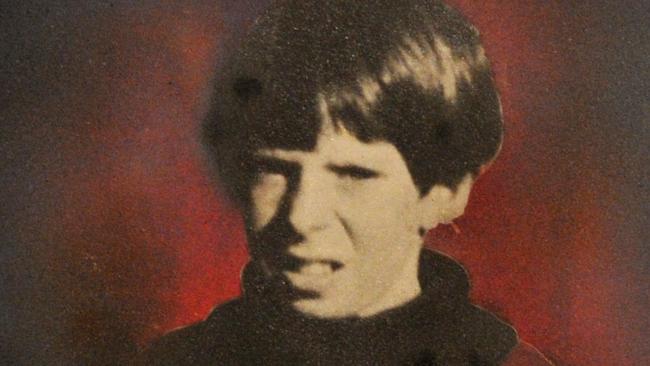

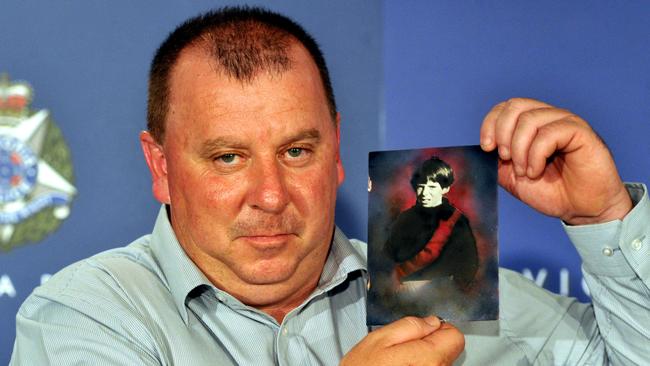

Specialist tracker dogs have come 47 years too late to help catch Terry Floyd’s killer, though they might still offer some solace to the boy’s grieving relatives.

If the two dogs brought to Avoca this weekend by a volunteer search dog group do trace Terry’s remains, it will give his surviving siblings some peace their parents never had.

Terry was 12 when he vanished in 1975 while waiting at Avoca for a lift to his family’s Maryborough home.

Australian police then, and now, don’t use specialist scent hounds the way some American states and most European countries do. Such a dog could hardly have saved Terry’s life.

But it might have led investigators to his body and then to a killer — who, instead, is still at large.

Police dogs are much admired. But, in Australia, their effective use is mostly limited to routine law enforcement because they are general purpose dogs, not honed trackers or trailers.

In abduction and missing persons cases, police dogs get photographed but rarely get results. “What police dogs are very good at,” says one search dog expert drily, “is catching car thieves after they dump a stolen car and run away.”

Some police dogs are great at locating money and drugs — popular in Sydney — and others tackle aggressive offenders who resist arrest.

But when it comes to lost people, they aren’t in the hunt. That’s a pity in a big country where people often go missing. Some are found alive. Some are found dead. Some, like poor Terry Floyd (so far), are never found.

Just last spring, two young aboriginal men almost perished in the Northern Territory after bogging their vehicle, walking in the wrong direction then becoming separated.

By good luck, teenager Mahesh Patrick hit a fence line and followed it to safety, and alerted searchers to his 21-year-old mate Shaun Emitja, saving Shaun’s life.

Police said the rescue was a “miracle”.

But why should it take a miracle? What if a trained scent hound had been available to be flown to the pair’s abandoned car? The sort of hound that Americans call a “man trailer”.

In America and Europe, scent hounds routinely find missing people — often children and old people. There are dozens of examples but one touches a parent’s heart. When a toddler went missing on a Minnesota farm, a bloodhound brought from Florida found the child had fallen deep into a haystack, where no one would have found her alive.

A happy ending — for the price of a man and a dog hired by the hour.

It takes four hours of training a week for up to two years to make a suitable hound “bombproof” enough to follow a cooling scent a long distance. Not a big investment to save lives, but still not done in Australia.

It’s not only the very young and very old who get lost. People who should know better sometimes take on nature and lose.

The then state government minister Tim Holding was lost on a hike at Mt Feathertop in 2009.

At least 80 searchers, including many police, spent two days in the mountains before he was spotted from a chopper. He had fallen 100m down a slope. A broken leg or concussion could easily have ended in tragedy.

Another intelligent, fit adult wasn’t so lucky: Stephen Crean, brother of Cabinet Minister Simon Crean, got lost and died of exposure near Thredbo in August 1985. His disappearance led to an intensive search involving two helicopters and 50 people — but no dogs able to track through snow.

Search and rescue police are skilled at accessing difficult spots to retrieve people. But it’s fair to say that although most emergency services people have specific skills, they are as unfamiliar with actual “man trailing” as the rest of us.

In June 2020, a 14-year-old autistic boy, William Callaghan, was lost at Mt Disappointment, half an hour’s drive from Melbourne’s outer suburbs.

It was cold overnight, William wasn’t warmly dressed and, being non-verbal, unlikely to answer searchers’ calls.

It was a big story within easy reach of city newsrooms. There were platoons of searchers on foot, on horseback, on motorbikes and 4WDs, joining police and SES members and anyone else who could get their high-vis on the news.

This army of 450 searchers was filmed mostly patrolling the road, calling to a boy who wouldn’t answer. Marquees, lighting plants, communications and satellite phones were trucked in and set up at huge cost.

Senior police did nice interviews about the innovation of playing the Thomas The Tank Engine sound track through a PA in the hope William would respond. People cooked sausages and onions, hoping the smell would attract him.

Meanwhile, the sort of hi-tech thermal imaging gear used in war zones was flown back and forth in helicopters. And rightly so. A human life is worth every effort.

But it didn’t work.

The whole costly, clumsy, complicated exercise made warm and fuzzy police public relations. But it was useless. On the third day, with hopes of a happy outcome fading, a lone bushwalker not linked to the official search went slightly deeper into the bush, further from the beaten track, and found the boy.

A miracle?

It was — a miracle of common sense and practicality that had nothing to do with the Dads’ Army of emergency services tooled up for a small war.

A day after William was rescued, people were still praising police for adapting search methods to suit an autistic child. As if those methods had worked when, in truth, they had failed spectacularly.

Question: if there were police dogs there at all, why couldn’t they track a boy who’d gone only a few hundred metres from the road? Or is it that once hundreds of searchers crowd a scene, normal police dogs get confused?

Another example. In April 2015, a younger boy, Luke Shambrook, also autistic, went missing from a campsite near Lake Eildon.

The search was huge and got bigger by the day but hopes were dying when a helicopter crewman finally spotted Luke in the undergrowth on the fifth day. He, too, didn’t answer searchers’ calls. If the chopper crew had missed him, Luke would have died.

When anyone is lost for more than 24 hours, it can so easily turn into a tragedy.

When someone is found, or “walks out” after days and nights, it is seen as a sort of miracle, because thirst and cold (or heat) kill people.

The common factor in these high-profile cases and far too many others is that if police dogs are used at all, they do not actually find the missing.

This is not knocking conventional police dogs. They are magnificent animals, trained to a high pitch by expert handlers to do specific tasks. But they are multi-purpose dogs, mostly german shepherds, selected for trainability, strength, bravery, intelligence and loyalty. They are an offshoot of the military’s wartime use of protective dogs, very different from hounds bred for centuries purely to trail living creatures by scent alone.

The charismatic all-rounders in police K-9 units can do the things the police require week in, week out: searching buildings or small suburban spaces for potentially dangerous suspects, grabbing aggressive offenders on cue, intimidating hostile people that outnumber police, and sniffing out drugs, cash or weapons in or around houses. All close range stuff.

Yes, some can track (and “trail”) by scent to a degree. But, in practice, it seems they are not called in early enough to find lost people in Australia — either that, or these “General Purpose Dogs”, as police rightly call them, are simply unsuited to long searches in rough country when there are too many distracting scents.

This is no criticism. It’s stating the bleeding obvious. So what’s the fix?

Our police forces have long looked to America and Britain for better methods. We send officers to study the latest FBI and Scotland Yard techniques. But, for some reason, Aussie police have never bothered with the sort of scent hounds used to find lost people and fugitives in many overseas jurisdictions.

The original bloodhounds, whose genes are in most hound breeds today, have been bred for one task since the seventh century. These specialist hounds are different from the working and pet breeds we are used to. Bloodhounds, especially, are hard work to train and maintain, which is why most Australians never see one.

They are stubborn, resist commands, slobber continually, they “bell” (between a woof and a howl) a lot, they dig deep and jump high to escape and they are so fixated on following scents that they’re hard to control.

This helps explain why police departments favour tractable all-purpose dogs, if not german shepherds then their cousin, the belgian malinois.

But cranky, slobbering bloodhounds are phenomenal trailing machines, often described as “a nose with a dog attached”.

The bloodhound and its relatives — beagles, foxhounds, harriers and coonhounds — have millions of scent receptors. Their instinct to follow scent can be harnessed to perform extraordinary feats.

Top hounds can be put on a scent that is hours or days old and follow it relentlessly.

The record (in America) is 200km, and good “man trailers” can follow a scent to the spot where their target got into a vehicle — and then the hound can point which direction the vehicle went.

Contrary to popular belief, they can follow a scent through or across water. Marine scientists use them on boats to locate specific varieties of whale manure for study.

In many American states, if someone is lost, trained hounds are on the job quickly. And save lives.

Here’s a hypothetical scenario, unprovable but thought provoking: what if a scent hound had been taken straight to the house where William Tyrrell vanished in 2014?

One sniff of the little boy’s clothes or bed and a search hound could have led to where William went. It would have narrowed the search to one direction — and indicated whether he had got into a car or was hidden nearby. For a trained hound, a routine task that might have saved millions of dollars and thousands of hours of useless searching.

If William was abducted and held, such a hound might even have saved his life.

Australian police chiefs make interesting choices. They spend millions on helicopters and changing uniforms and new pistols, but won’t spend peanuts on dogs that save lives.

It’s not as if some police dog handlers don’t know that.

One state K-9 unit (not Victoria) quietly approached Australia’s leading bloodhound breeder recently to order a pup to train for tracking.

But before the pup was delivered, senior police blocked the purchase because of “lack of funding”. Go figure.

Police can be pigheaded about change. Dog squads apparently refuse to put GPS trackers on their dogs’ collars (you can only speculate why) which has led to the sad case of Queensland’s most costly lost mutt: police dog Quizz, lost in bush near Ipswich last month, prompting a huge search.

A GPS tracker would have located Quizz quickly. So would a bloodhound or a beagle or any other hunting breed trained to follow one scent.

Instead, the Queensland coppers are talking rewards and appealing to the public.

It doesn’t inspire great confidence.

PAWNOTE: This column was inspired by Marg Moloney and her hungarian vizsla, Amber, who in half an hour last week traced the four-day-old scent of a lost Rule family cat. The cat was found in a distant backyard in exactly the direction Amber pointed.