Secrets in Calabrian mafia hit on Donald Mackay buried with cunning gun dealer George Joseph

Like a doctor or priest, George Joseph knew a lot of secrets. And to the end, he feared that one of them might get him killed.

Andrew Rule

Don't miss out on the headlines from Andrew Rule. Followed categories will be added to My News.

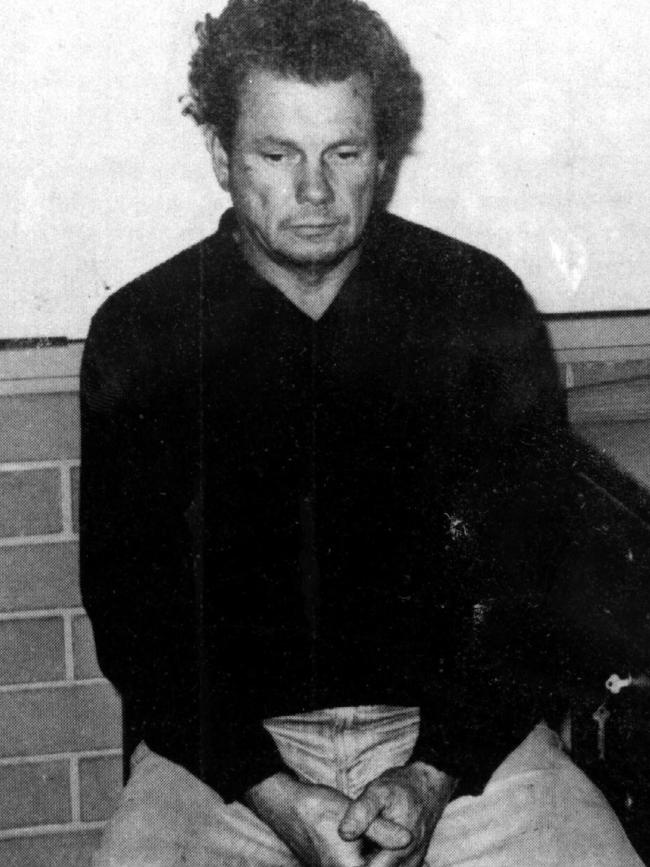

George Joseph had a soft voice, a deceptively gentle manner and some very dangerous contacts stretching back to the 1950s.

By the time he died last week, the cunning old gun dealer had outlived nearly all of them. But he never forgot the rules that kept him alive so long.

In recent years, he would call crime reporters regularly and talk as long as they let him, though never about certain aspects of his long and devious life.

That’s how it was in George Joseph’s business. Like a doctor or priest, he knew a lot of secrets. And to the end, he feared that one of them might get him killed.

In office hours, he was a legitimate gun shop owner, starting out in North Fitzroy in the 1960s then taking over a well-known shop in Victoria St, West Melbourne.

But the amiable Joseph had a dark side. He was a black market gun dealer who could source nearly anything for anyone if the price was right, including Uzi submachine guns and unregistered pistols. That’s how he got to pay for big American cars.

Dealing both above and below the counter, Joseph had a wide group of clients. They ranged from the legitimate — farmers, professional shooters, hunters, target shooters and police — to the illicit: armed robbers and organised crime bosses and, inevitably, the odd hit man.

His store was around the corner from the Vic Market near the Don Camillo coffee shop, known for its colourful clientele.

When the Griffith cell of the Calabrian “Honoured Society”, ’NDrangheta, voted to murder Donald Mackay because he was too straight to blackmail, middlemen reached out to Joseph to recruit an outside hit man.

The Calabrians didn’t want it to look like a mafia hit. The upstanding Mackay, a churchgoing father of four with a furniture store in Griffith, was aiming for parliament on an anti-corruption ticket.

Unlike many who admired him, Mackay was game to stand publicly against the bent cops and crooked Calabrians growing rich from cannabis crops on local irrigation blocks.

If Mackay got to win the seat for the Liberal Party, he would be able to expose the relationship between the Calabrian cannabis cartel and their longtime pet politician, Al Grassby, the local member who had been appointed Immigration Minister in the Whitlam Labor Government before losing the seat to the National Party in 1974.

Because Grassby had been given a prize Government job after losing in 1974, he still had enough “pull” in Canberra to help his mafia paymasters. Mackay was a threat to that. But the plot to kill him had to be executed by remote control so he disappeared in a way that could never provably be linked to the Calabrian “Honoured Society”.

Gianfranco “Frank” Tizzoni wasn’t one of the Griffith clan, whose members were related to each other by blood, marriage and birthplace. But as an Italian speaker with shady connections in Melbourne, he was a favourite helper of the Calabrians’ friendly fix-it man “Aussie Bob” Trimbole.

Trimbole was privy to a secret meeting of Calabrian bosses in Griffith in May 1977, in which they voted to kill Mackay. Trimbole flew to Melbourne and met Tizzoni in Balwyn. Tizzoni, a sometime private investigator who’d switched to running slot machines, said he knew who to ask … George Joseph.

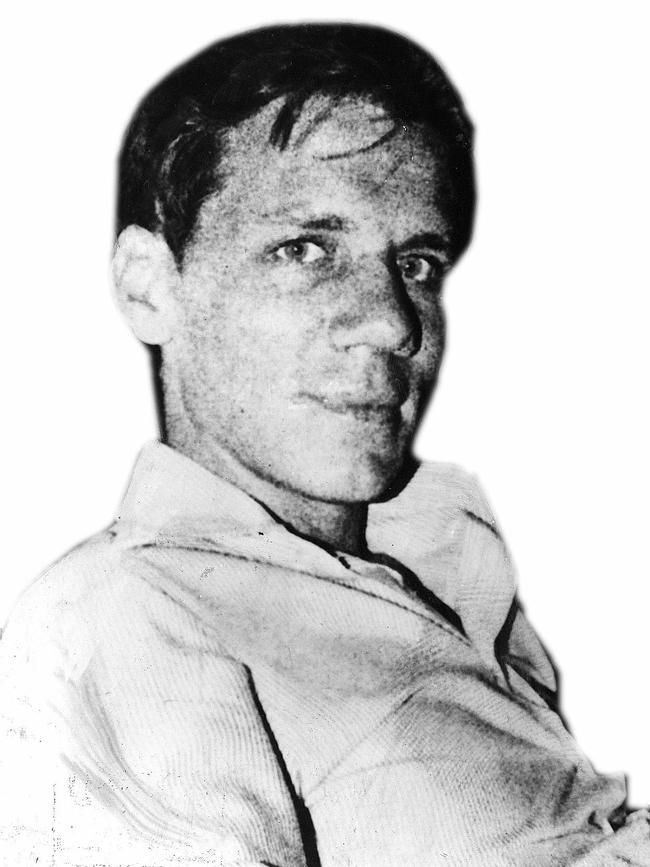

Tizzoni asked Joseph if he knew a contract killer. Joseph did: a deadly Australian-born gunman, Jim “Iceman” Bazley, survivor of the docks wars of the 1960s and 1970s and friend of another old “gunnie”, Billy “The Texan” Longley.

Bazley bred poodles with his wife Lillian, sister of another old-time gunman, Horatio Morris.

Joseph drove Bazley to meet Tizzoni in Parkhill Rd next to Kew cemetery near Belmont Ave, where Graham “Munster” Kinniburgh would be killed in his own driveway nearly three decades later.

The three sat in Tizzoni’s bronze Mercedes and clinched the deal. Bazley, introduced as “Fred”, said he wanted $10,000, a photograph of Mackay and a description and registration number of his car.

The instructions were that the hit man wasn’t to use a shotgun (because shotguns were traditional mafia weapons) and to guarantee the body would never be found. Bazley said in that case he would have to “rip the guts good”, implying he would dispose of the body in water and wanted to be sure it wouldn’t float.

After a false start in which Bazley failed to lure Mackay to a lonely spot at Jerilderie, he killed him in the carpark of a Griffith pub on July 15, 1977, most likely with Tizzoni’s help to shift the body.

The only clues were bloodstains — and three .22 shells ejected by a French-made Unique pistol, a small weapon easily hidden in a pocket, shoulder holster or belt. Joseph had supplied it.

It seems Bazley had a weakness for pistols as well as poodles. The old pro made the rookie error of keeping the Unique that Joseph had sold him. The weapon helped link him to the Mackay conspiracy long after a dog walker found the shallow grave containing New Zealand drug couriers Douglas and Isabel Wilson at Rye in 1979.

The Wilsons, also killed on Trimbole’s orders, were buried near a holiday house Bazley and his wife sometimes used. But the connection would not have been made if the middleman Frank Tizzoni hadn’t fallen into the web of deceit he’d helped weave.

In March 1982, a Victorian policeman, John Weel, pulled over two cars heading from the Riverina into Melbourne loaded with what Griffith locals called “Calabrese corn” — cannabis worth big money on the street.

We all knew exactly who he was following and why, but the arrest was staged as if it was a coincidence.

The Victorians wanted to arrest Tizzoni south of the border and pressure him to sell out his co-conspirators in the Mackay and Wilson murders.

They took him to his asparagus farm at Koo Wee Rup as a safe house, guarded him and worked on him.

Tizzoni, not related to the Calabrians so much as hired by them, flipped on his associates, including Joseph.

Faced with the same pressure, and desperate to get a lighter sentence, Joseph also gave some prosecution evidence in a conspiracy case against Bazley, who also faced murder charges over the Wilsons.

Joseph got out of jail years before Bazley did. But he lived in fear he would be killed for talking.

The truth was that with Tizzoni’s testimony, Bazley was headed for a long sentence in any case. But that was cold comfort for Joseph.

Although Tizzoni and Joseph had both held back some of what they knew in the witness box, it was natural they were nervous about crossing the mafia and its deadly old hit man.

Tizzoni quietly returned to his home region in Umbria in central Italy, where he ran a garage until (former Herald Sun crime editor) Keith Moor tracked him down in late 1987, six months before the fugitive died of natural causes.

Joseph, meanwhile, laid low. He lived in the northeastern suburbs around Templestowe, looking over his shoulder and being very careful on telephones. Like a priest who breaks the confessional seal, an underworld gun dealer who talks might be seen as a dangerously loose end by those who paid for Bazley to kill Mackay and the Wilsons.

For all Joseph’s caution, he still knew his way around the underground gun scene. That, of course, meant he was more useful alive than dead to certain people during the underworld war, which erupted in the late 1990s and was still raging in 2003.

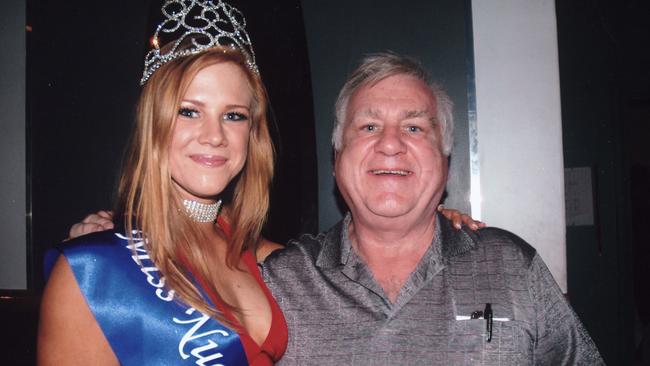

After a rash of shootings, Joseph secretly introduced an Adelaide sex shop and brothel owner, Bill Nash, to a treacherous associate of the equally treacherous Mario Condello, bent lawyer and member of the Carlton crew. Condello justifiably feared for his life and badly wanted firepower.

Condello’s offsider picked up a big cache of guns from Nash. It included an Uzi submachine gun, a .357 magnum revolver, a Bentley pump-action shotgun and several pistols with silencers.

It might have been coincidence, but there were several gangland murders in the months after Condello took the first batch of guns in early 2003. Unfortunately for Condello, Australian Crime Commission agents nailed his associate and persuaded him to “roll” on him and Nash. The agents set up a sting, luring Nash to sell a shipment of guns to an undercover officer.

The Adelaide guns didn’t save Condello. He was shot dead in the garage of his Brighton house in February 2006, exactly 16 years ago today.

Nash ended up doing time, of course. But, this time, Joseph stayed out of jail. It’s possible he might have been able to trade his way out of trouble with a few quiet words.

It seems he and Nash had more in common than gun dealing. They were both judges in the Miss Nude Australia competition.

Police and the occasional reporter stayed in touch with Bazley and Joseph to the end, hoping either veteran villain would drop a hint about where Donald Mackay’s body ended up.

In 2013, police acted on an anonymous tip-off and used machinery to dig up spots on a property at Hay in NSW. No result.

Bazley died at age 92 in 2018, still stating he didn’t kill Mackay. Trimbole the mafia puppet master had died as a fugitive in Spain in 1987, not long before Tizzoni.

Now that George Joseph has gone, there’s no one left who might have unravelled what happened to Donald Mackay’s body.

Joseph spent his last few years calling crime reporters to push a persistent claim he’d been rorted of a large sum by a lawyer handling his affairs while he was jailed.

His complaint sounded like the rambling of an addled old man, because lawyers rarely rob clients who might get them shot.

Rambling or not, George Joseph was never so addled that he talked about the Mackay case. He wanted to die in his sleep and he did.