Andrew Rule: $50m dilemma at heart of iCook slug saga

It’s hard to know who wants to cover up Slug Gate most. But some big players give the impression of trying to nobble effective investigation of who stood to gain from the saga.

Andrew Rule

Don't miss out on the headlines from Andrew Rule. Followed categories will be added to My News.

How high does the slug slime go?

That’s the $50 million question hanging over the State Government, Victoria Police, Dandenong Council and Knox City Council as “investigation” of the sleazy “Slug Gate” saga crawls along at snail’s pace.

It’s hard to know who wants to cover up Slug Gate most. But some senior police, who may well be named in a future court action, give the impression of trying to nobble effective investigation of who stood to gain from the plot to plant a garden slug in a Dandenong food processing plant on February 18, 2019.

That was the day that the wonderfully-named Elizabeth Garlick fronted at the I Cook Foods plant in Zenith Rd, wearing a coverall smock with tissues spilling from its front pockets.

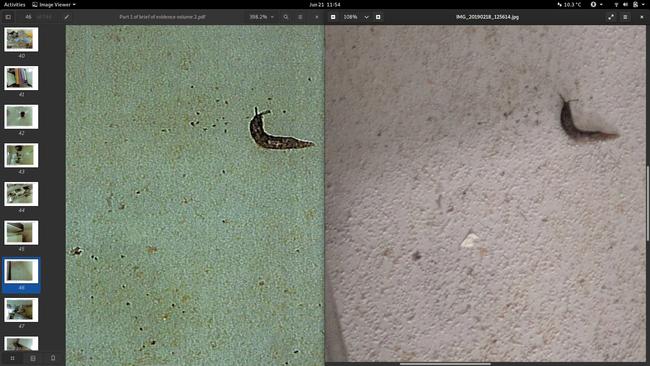

Garlick, a newly-hired health inspector with Dandenong Council, went to the back of the food-preparation area and squatted out of sight of security cameras for exactly 17 seconds.

Then she stood up, pointed theatrically towards the spot where she’d crouched and declared she’d “found” a slug.

This was a variety of the common garden slug — which, it turns out, isn’t that common. In fact, that particular subspecies isn’t found within many kilometres of Dandenong, according to experts, who say it’s hard to believe it appeared on a hot summer day, given that slugs are nocturnal and move around on cool, moist nights.

As luck had it, Garlick was being escorted by Michael Cook, brother of I Cook Foods principal Ian Cook, whose family business has grown steadily since it began 35 years ago. When Garlick photographed the slug, Michael Cook wisely also photographed the scene.

Which is lucky. Because when Garlick later produced a photograph of the pet slug, the picture did not include a piece of tissue that had been next to it at the time. We know this because Michael Cook’s virtually identical photograph has both slug and tissue. And that is the heart of a $50m dilemma for the plotters.

![Ian Cook with retired Detective Sergeant Paul Brady [left] and retired Detective Inspector Rod Porter [right], with evidence submitted to Victoria Police.. Picture: Alex Coppel.](https://content.api.news/v3/images/bin/4bfb64e4c29e42fcd45d34803f079e66?width=650)

The riddle of the vanishing tissue was answered later when an honest co-worker of Garlick’s at Dandenong Council, Kim Rogerson, blew the whistle — revealing that the Garlick slug picture had been “photoshopped”. It was shocking, but hardly a surprise in the increasingly murky circumstances surrounding Slug Gate.

What has been claimed to be orchestrated industrial sabotage has turned into what looks awfully like an orchestrated cover-up. One that affects people all the way up to the embarrassed health department chief Brett Sutton — who’s yet to explain how he came to be embroiled in an apparently barefaced attempt to run I Cook Foods out of business with a bogus health scare. There are signs, however, that he is prepared to throw a senior health department colleague under the karma bus.

The story behind the story is that I Cook Foods, which produces chilled pre-packaged meals, had a commanding market share among Melbourne aged-care homes and hospitals and meals-on-wheels until 2010, when a bunch of councils persuaded the State and Federal Government of the day to use taxpayer dollars to launch a competitor to grab some of the action.

This ambush was not exactly a fair fight but that has never stopped governments and bureaucracies from trampling small business. A key player in the birth of the new council-backed business, which they named Community Chef, was Dandenong Council.

Community Chef has done nothing but bleed taxpayers’ money since it started. It has bled so many millions, in fact, that it puzzles observers who can do sums without counting on their fingers.

But taxpayers’ loss is usually someone’s gain. Despite Community Chef’s relentless loss-making, it seems that someone, somewhere, must have decided that this golden goose was too valuable to let die merely because it couldn’t legitimately compete with the efficient I Cook Foods.

The logic was brutal: if I Cook Foods was killed off, then Community Chef would be the only supplier for local institutions and so would automatically be deemed an Essential Service — eligible for bottomless Government funding. The only thing standing between Community Chef and a taxpayer-funded bonanza was I Cook Foods.

The whistleblower Kim Rogerson makes it clear that the plot to slug iCook behind the play was cooked up at Dandenong Council. That’s bad enough, and at some point at least some of the allegedly guilty parties should have to answer for their actions.

But the really slimy part of Slug Gate is the cover up on top of cover up. The plotters who ruined the Cook family’s $25m business have compounded the offence by trying to hide tracks as obvious as the trail left by an elephant in snow.

The story goes back to when an elderly woman at Knox Private Hospital died in early 2019 after taking ill at a nearby aged care home.

The patient’s name was Jean Painter. Dandenong Council and the Health Department seized on her death as an excuse to use draconian powers to close down commercial kitchens in which food poisoning or contamination occurs.

But the truth, soon uncovered, was that Jean Painter had in fact died of a longstanding heart condition unrelated to her listeria symptoms of diarrhoea and headache — a temporary illness soon proven to have no link with I Cook Foods.

So far, so bad. It could have ended there — except that Brett Sutton, apparently briefed by senior department officers, insisted on calling a media conference conducted with all the subtlety of a drive-by shooting.

Despite the department’s own laboratory testing clearing the company of any breach of food safety rules, Sutton made inflammatory and false claims that publicly trashed the Cooks’ brand — and led to more than 10 tonnes of good food worth $700,000 to be sent to the tip.

Sutton claimed — wrongly, as his own experts might have to swear in court — that I Cook Foods was the source of a serious listeria outbreak which could kill “thousands” of people. He made a point of naming the business, which was totally unnecessary (even if his baseless claims were true), as no I Cook Foods products are sold directly to the public.

The department did not seem interested in whether there was a public health risk — which there wasn’t — so much as in finding an excuse to bash I Cook Foods. This is the guts of the case that Ian Cook’s lawyers are preparing against the State Government and Dandenong Council, if not Victoria Police.

When the Cooks get the case to court to claim damages, their lawyers will be alert to the possibility of arguing that the damage done to I Cook Foods was not just misguided but malicious.

Ian Cook is shocked by the treacherous treatment at the hands of people and institutions he had trusted all his life.

The ordeal of an honest health inspector, Ray Christie, underlines Cook’s point. Christie was working for the City of Knox in February 2019, when the health department seconded him to investigate the details of Jean Painter’s death at Knox Private Hospital a couple of weeks earlier.

Christie wrote a report on what he found: that Mrs Painter had been restricted to a “soft diet” prepared wholly in the hospital’s own kitchen. He made it clear that the ill woman had not eaten any pre-packaged sandwiches from I Cook Foods.

Christie was surprised and disturbed that his report was apparently ignored by the health department officers who briefed Brett Sutton before the media conference that ruined I Cook Foods.

When Ian Cook found Christie and spoke to him in March 2019, Christie was sympathetic and told him: “You need to get my report”. But when Cook later applied to Knox for Christie’s report under FOI, all 34 pages were redacted.

When Cook contacted the Knox City FOI officer, Damian Watson, the clearly uncomfortable Watson told him he had approved and signed the redaction letter at the direction of senior council figures.

Watson said the report had been totally blacked out using the baseless excuse that it was “irrelevant” but admitted his personal opinion was that it should be released uncensored “in the public interest”. It seemed to Cook that this relatively junior official smelt a rat above his pay grade and wanted no part of it.

As for Ray Christie, he told Ian Cook he was so disgusted that he resigned after allegedly being harassed and intimidated.

The bottom line, says Cook, is that the City of Knox effectively suppressed a report relevant to a case in which his company faced 96 charges that could have landed him in jail. Such suppression is a serious offence, which is why a Det. Sen. Const. Robert Baker was doing his job properly by taking a statement from Ray Christie — and arranging to take one from Cook.

The detective’s no-nonsense approach impressed Cook, who had been frustrated by months of suspiciously slow and ineffective police work on the slug-planting scandal.

On June 29, Det. Baker called Cook to invite him to Knox police station on Saturday, July 4, to make a full statement about Knox City’s hiding of evidence and whether it was linked to the Department of Health.

But on that Friday, just three days later, Det. Baker called Cook to say the interview was off. When the flabbergasted Cook asked why, the Detective said “his boss told him that the boss above him” directed that the complaint be “merged with” the slug investigation still supposedly under way with Casey police (where it had ended up after Dandenong police had passed it to Moorabbin because of a “conflict of interest”).

Ian Cook is learning a bit about politics, police and human nature. Something, he says, stinks in the state of Dandenong.

His challenge will come, of course, when a pinstriped lawyer offers him tens of millions of public money in a confidential settlement to avoid a huge civil action that could almost swing an election. Not that such a settlement should stop IBAC from peeling back several layers of slime.

To be continued …