Misfired ‘Chinese fire’ rockets and stampedes killed Parisian fireworks spectators in 1743

SPINNING displays of “Chinese fire” staged by Italy’s five Ruggieri brothers entranced Parisians in 1743. But when they and a competitor set off their works at the same time in 1749, misdirected explosions and a stampede as spectators attempted to flee killed 40 people and left 300 injured.

Today in History

Don't miss out on the headlines from Today in History. Followed categories will be added to My News.

BILLED as Gardens of Flowers, Magical Combat or The Palace of Fairies, theatrical dramas staged by Italy’s five Ruggieri brothers entranced Parisians in 1743.

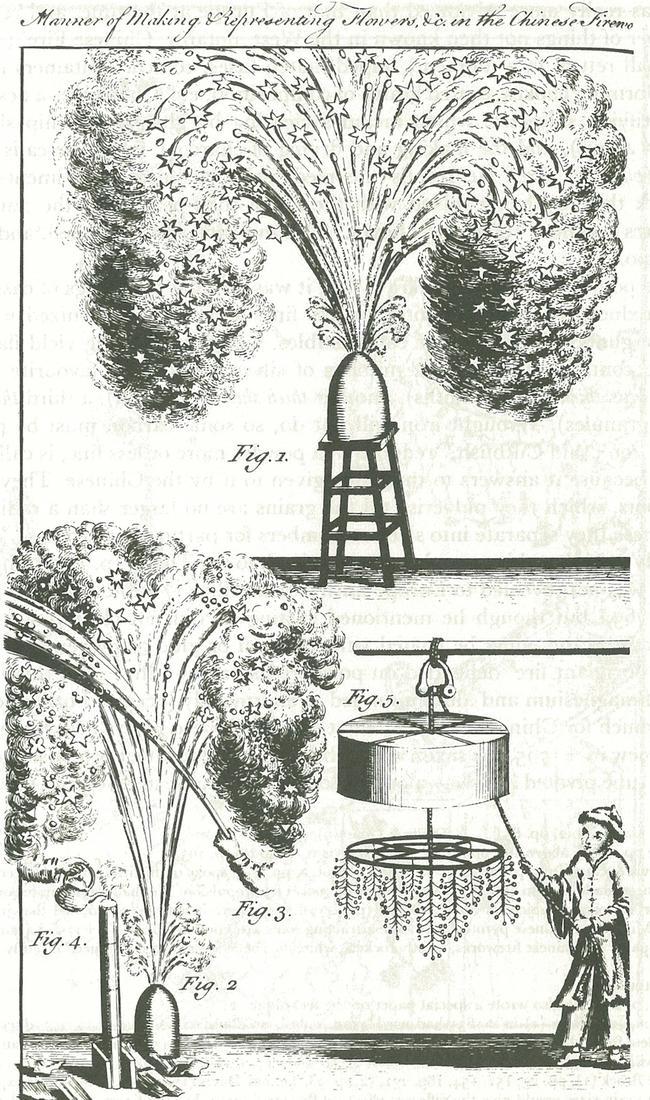

But tensions with competitors ignited six years after the Ruggieris brought their spinning displays of “Chinese fire” to the Comédie Italienne in Paris.

When the Ruggieri’s and a competitor set off their works alight at the same time in 1749, misdirected explosions and a stampede as spectators attempted to flee killed 40 people and left 300 injured.

Unlike the modern multicoloured explosions that will light up Sydney tomorrow night, Ruggieri displays of up to 6000 rockets were limited to red, yellow and orange.

Fireworks evolved from a formulation now known as gunpowder, believed to have been invented by chance in China about 2000 years ago. Variously ascribed to a mistake by a cook or an attempt at a longevity potion, the mix of sulphur, charcoal, and saltpetre reacted dramatically when heated. Han Dynasty scientist Wei Boyang in 142AD wrote the first text on gunpowder, describing a concoction of three powders that would “fly and dance” violently. Wei’s mix used 15 parts of saltpetre to three parts charcoal and two parts sulphur.

In the Tang Dynasty in about 700, emperors were entertained by “magical” firework displays using gunpowder. By 904, Chinese inventors used gunpowder as a weapon in crude rockets by putting small stone “cannonballs” in bamboo tubes. The gunpowder was ignited at one end to blast out the cannonballs.

Gunpowder reached Arabia around 1000 and Europe by about 1200, when it was again rapidly adapted for weapons such as muskets and cannons.

But European rulers also enjoyed fireworks displays, illuminating their castles and public squares to celebrate special occasions. Italian artist Michelangelo designed a 90-minute display for Pope Julius II at Rome’s Castel Sant’Angelo fortress to celebrate the festival of Roman saints Peter and Paul in about 1481. Featuring a girandola, or pinwheel, Michelangelo’s display was designed to “spit flames and fire” in imitation of an eruption of Stromboli volcano off the Sicilian coast, and was later reworked by Lorenzo Bernini.

English subjects witnessed a fireworks display in January 1486, to celebrate Henry VII’s marriage to Elizabeth of York, a union that also ended the War Of The Roses. Their son Henry VIII continued the tradition: a four-day celebration of the coronation of his second wife Anne Boleyn in May 1533 featured barges on the river Thames carrying “wild men casting fire and making a hideous noise”, and a “great red Dragon continually moving and casting forth wild-fire”.

Their daughter Elizabeth I favoured massive dragons with papier-mache scales, built on a wooden frame and stuffed with firecrackers to “breathe fire”, which sometimes included mock battles against a second dragon. Elizabeth also appointed a “Fire Master of England”, possibly after a mock battle staged for her benefit in 1572 by Robert Dudley at Kenilworth Castle in Warwickshire fired misdirected fireballs onto a nearby town, burning down houses and killing one resident.

German composer George Handel composed Music for the Royal Fireworks for George II, to accompany fireworks in London’s Green Park in April 1749, staged to celebrate the end of the War of the Austrian Succession and the signing of the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle in 1748.

And despite their talent for crosses, polygons, wheels and stars fixed on iron axles to create spinning bursts of fire, even the Ruggieri brothers were not immune to pyrotechnical disaster. At a celebration of the marriage of the Dauphin of France, aged 15, to Austrian Archduchess Marie-Antoinette, then 14, in 1770, Petroni Ruggieri’s celebratory display spooked the crowd when a sudden wind gust scattered partially exploded rockets.

Many spectators were trampled as the crowd rushed towards the narrow Rue Royale. The official government death toll was listed as 133, although it was likely much higher.

Ruggieri descendant Claude Fortune helped redeem the family name in the early 1800s when he described “green fire”, created with four parts of verdigris (copper carbonate) and two parts blue vitriol (copper sulfate) and one part sal ammoniac (ammonium chloride).

But Ruggieri’s work likely drew on experiments by Russian professor Mikhail Lomonosov at the St Petersburg Academy of Sciences, and artillerists Mikhail Danilov and Matvei Martynov, who created fireworks displays for Russian Empress Elizabeth Petrovna. Martynov, as chief fireworker, and his assistant Danilov first claimed the discovery of coloured fire in the 1750s.

Originally published as Misfired ‘Chinese fire’ rockets and stampedes killed Parisian fireworks spectators in 1743