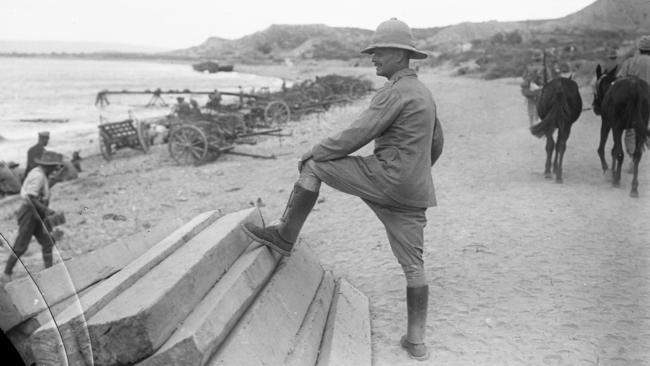

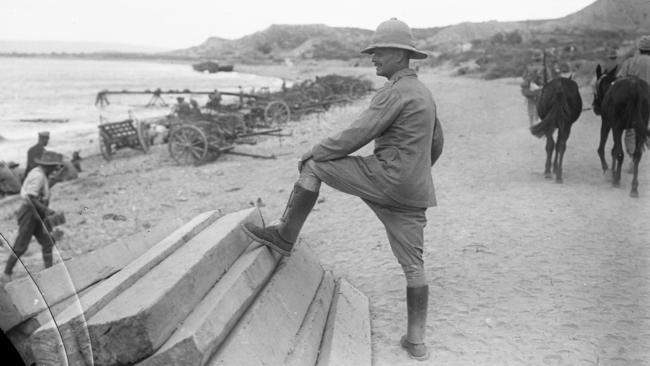

Many Gallipoli troops had never heard of the Anzacs

A century ago today, Australian and New Zealand troops were enjoying the balmy beauty of Lemnos, just 50km from the Turkish coast and gateway to the Dardanelles. Most had never heard the term Anzac.

Today in History

Don't miss out on the headlines from Today in History. Followed categories will be added to My News.

A century ago today, Australian and New Zealand troops were enjoying the balmy beauty of Lemnos island, just 50km from the Turkish coast and gateway to the Dardanelles.

At that stage — with a Gallipoli invasion imminent — most had likely never heard the acronym coined for the combined Australian and New Zealand Army Forces at the end of 1914 by British officers making battle plans in central Cairo.

Small contingents of the combined Australian and New Zealand Army Corps had already seen battle in early February 1915, when Turkish Ottoman troops marched across the Sinai Desert in an attempt to claim the Suez Canal.

The first Australian and New Zealand troops had sailed from King George Sound, Albany, initially bound for Europe, on November 1, 1914. Australian Light Horse commander Harry Chauvel, in England, was concerned about Australian troops disembarking in England to train over winter and suggested they train instead in Egypt, where political manoeuvres were moving rapidly.

Egyptian Khedivate, or leader, Abbas II was increasingly hostile to British influence in Egypt, then still a virtual Ottoman vassal state. Britain responded on November 5, 1914, by proclaiming a Sultanate of Egypt, with a protectorate around Cairo and the Mediterranean coast.

Fighting on the Western Front in France had also reached a stalemate, so the British War Council decided victory could rest with attacks on German allies Austria, Hungary and Turkey. Britain was also concerned about defending Egypt against Ottoman attacks, and quelling uprisings by Ottoman sympathisers within Egypt.

On December 1, 30,000 Australian and New Zealand troops, with 12,000 horses, sailed through the 160km Suez Canal. Already aware their attention would focus on Turkey, Australian and New Zealand troops disembarked at Alexandria on December 9 and were dispatched to Cairo. Chauvel arrived at Port Said on December 10.

On December 19, British sympathiser Hussein Kamel assumed the title of Egyptian Sultan. Two days later, British Major-General William Birdwood arrived from India to organise Australian and New Zealand forces into a single army corps.

The corps at first comprised only the Australian 1st Division, along with the New Zealand Infantry Brigade and two mounted brigades, the Australian 1st Light Horse and the New Zealand Mounted Rifles.

Another convoy carrying an Australian infantry brigade and two light horse brigades arrived shortly afterwards. With the first arrangement of two extra infantry brigades as the New Zealand Division, along with a Mounted Division, judged unsatisfactory, the New Zealand and Australian Division was formed, with two infantry brigades and two mounted brigades.

Unit diaries refer to the force as the Australasian Army Corps, following sporting practice at the time when New Zealanders and Australians competed together as Australasia. After New Zealand protested against losing recognition, the name Australian and New Zealand Army Corps was adopted. As material addressed to the A. & N.Z. Army Corps accumulated outside the corps’ headquarters at Shepherd’s Hotel, the abbreviation was deemed too cumbersome.

Birdwood wrote in December 1915 that “When I took command of the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps in Egypt a year ago, I was asked to select a telegraphic code address for my army corps, and then adopted the word Anzac.”

The British commanding officer of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force General Sir Ian Hamilton credited himself with using Anzac for convenience. In April 1916, he wrote: “As the man who, first seeking to save himself the trouble, omitted the five full stops and brazenly coined the word Anzac …”

But in his World War I history, Australian war historian Charles Bean explained British Army Lieutenant A.T. White coined the word in response to a query from Major Cyril Wagstaff early in 1915.

Wagstaff, a junior member of Birdwood’s staff, mentioned to clerks in the General Staff office that a convenient word was needed as a code name for the Corps. Big initials on cases outside the clerk’s room displayed A. & N.Z. Army Corps. A rubber stamp for registering correspondence had been cut with the initials A & N.Z.A.C.

Replying to Wagstaff, White reportedly suggested “How about ANZAC?” Wagstaff proposed the word to Birdwood, who approved.

But Bean also noted “the word had already been used among the clerks. Possibly the first occasion was when Sgt G.C. Little asked Sgt H.V. Milligan to throw him the ANZAC stamp”.

Bean’s account also explained “it was, however, some time before the code word came into general use, and at the Landing many men in the divisions had not yet heard of it”.

Originally published as Many Gallipoli troops had never heard of the Anzacs