Leaving Gallipoli wasn’t the end of the ordeal for the Anzacs

The Gallipoli evacuations happened a century ago this week, but for many the ordeal didn’t end when they left the peninsula.

Today in History

Don't miss out on the headlines from Today in History. Followed categories will be added to My News.

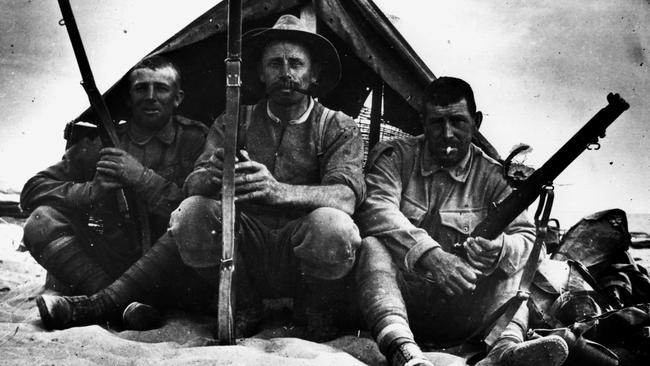

When the last Australians and New Zealanders left the beaches of Gallipoli in the evacuation of December 18-20 1915, they mostly felt enormous relief. They had feared the Turks would spill out of their trenches and rush the retreating force, causing mayhem and casualties. But they were also relieved to be finally turning their backs on the beaches and hills where the pointless destruction of so many lives had taken place.

Some were initially reluctant to leave, knowing dead mates were left on that foreign shore and the job they had set out to do had not been finished. But generally, the Anzacs were glad to leave the place where they had lived in fear of death, battling heat, thirst, flies, dysentery, sometimes boredom and, in recent weeks, biting cold and frostbite.

Yet for many of the men the ordeal was far from over. They would be sent to other theatres of war, some more hellish than anything they had seen at Anzac Cove.

The evacuation had been an impeccably planned and timed affair.

The number of soldiers on the peninsular had been slowly reduced in November and early December, which was what would have been expected for an occupying force getting ready for a slowdown over winter.

Otherwise the Anzacs carried on as usual, eating, sleeping, sniping, throwing grenades, swimming and even playing cricket, right up until the main evacuation. The Turks suspected something was afoot but even as the Anzacs boarded landing craft to begin the main evacuations in the dark on December 18, they rigged mines to explode and guns to fire, convincing the Ottomans to stay put in their trenches.

There is some debate over who was the last Anzac to leave. In his official history of the Anzacs in World War I Charles Bean wrote that it was Colonel John Paton, but evidence later emerged that Captain Charles Littler was the last man out.

The boats took the men to waiting ships which then took the injured to Lemnos and Imbros, while the able-bodied were sent to Egypt. A lucky handful were sufficiently recovered from wounds to be shipped home, where they were largely welcomed as heroes.

Those who arrived in Egypt enjoyed a bit of leisure time, but were soon told they were needed to defend Egypt. There were fears the Ottomans, having been freed from the need to commit so many troops to Gallipoli, would attempt an assault there.

Along with the thousands of troops sent to Egypt to train for service in Gallipoli before the decision had been taken to end the campaign, a flood of recruitment in the wake of the Dardanelles campaign had made more Anzac troops available.

Hardened Gallipoli veterans were now reorganised alongside the fresh troops into an expanded AIF. Their first major task was to help defend Egypt.

Gallipoli veteran Harry Chauvel was given command of the 1st Light Horse. His cavalry would remain in the Middle East and play a crucial part in the Allied campaign to capture major Turkish strongholds in the Levant.

Mounted soldiers who had suffered the frustration of losing their mounts to toil in trenches in Gallipoli now returned to horseback warfare, fighting a mobile campaign through searing summer heat and freezing desert nights in winter.

Troops who had experienced the frustration of assaulting Turkish trenches in Gallipoli took part in more successful assaults such as the charge on Beersheba in 1917.

Meanwhile the expanded infantry divisions were sent to Europe. They would find that the trench warfare of the Western Front, while it shared many of the same horrors as Gallipoli, was on a much larger scale, with far more mud, blood, rats, bullets, bombs and misery.

The experience of Gallipoli veterans resulted in the Australians playing a critical role in major battles toward the end of the war under leaders such as General John Monash who had served at Anzac Cove. By the time the Armistice ended the war in November 1918, Anzacs who had tried to live down the defeat of Gallipoli had witnessed some of the greatest triumphs and greatest tragedies of the World War I.

OUR LOST SOULS

● Of the more than 295,00 Australians who served in World War I, about 61,000 died.

● More than 46,000 Australians died on the Western Front, out of 250,000 who served there.

● About 1400 died in the Middle East campaign out of around 40,000.

● By comparison about 8700 died at Gallipoli out of a force of 60,000.

Originally published as Leaving Gallipoli wasn’t the end of the ordeal for the Anzacs