Robert Farquharson: The dad who killed his three sons by driving into Winchelsea dam

THE investigating officer could list more than 10 reasons why Robert Farquharson would deliberately kill his sons by driving into a dam. He could think of only one to suggest it might have been an accident.

True Crime Scene

Don't miss out on the headlines from True Crime Scene. Followed categories will be added to My News.

WILL Kelly’s recollections are hazy. It was a windy day and a tight match. His mate Jai was full-forward, a bustling presence in an unbeaten team. Afterwards, everyone celebrated “with the dads” in the family room of Winchelsea’s bottom pub.

Kelly is 22, a builder, and flushed with tales of last weekend’s football end-of-season festivities. It’s harder to cast back 10 years to that under-12 premiership, even if his only flag ought to be one of his most cherished memories.

The players paraded in their premiership medallions that afternoon.

Some wore them again a couple of weeks later to the little red church with the slate roof. Others came in Scout outfits, Kelly his school gear.

They all slumped and quivered in a uniformity of despair. Kelly was saying goodbye to his close friend and teammate, Jai Farquharson.

The whimpers were replaced by a howling that day; even the swarm of national media was enveloped in the unbearable sadness.

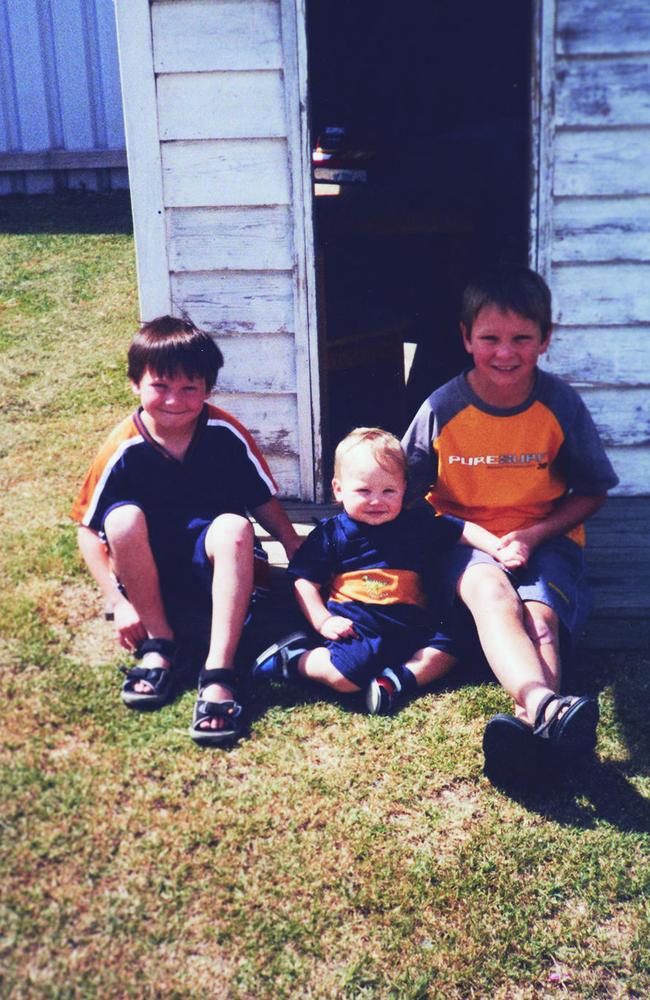

Jai, 10, with younger brothers Tyler, seven, and Bailey, two, had drowned in a dam. Their father, Robert, had swum to safety after their car plunged from the Princes Highway.

TRIPLE MURDER STILL HAUNTS TOWN

Kelly can remember first hearing the news. His mother warned him before he walked to school. It was the Monday after Father’s Day. On arriving, he recalls, “it sort of hit you hard”. Everyone was acting “very funny”.

“The next day, the first few days, it just seemed he was sick,” Kelly says. “Everyone had a couple of days off once a year when you were sick. But Jai just never came back.”

Jai’s eulogists spoke of his love of sport. He had slept the night before the grand final in his footy gear. Tyler had the cheeky grin, Bailey a pet cockatiel on his shoulder.

There was Jai’s karate and cricket, but Kelly remembers his hunger for footy. Jai was a straight kick, Kelly now recalls, a skill honed over many hours by his father.

Everyone was “pretty flat” in the days that followed; for years, one of Kelly’s mates would cry each time he passed the dam site. They were tight — they still are — and Kelly rallied the boys for schoolyard downball sessions. He was old enough, smart enough, to grasp the murmurs. He knew that Jai’s parents had separated and that “Robbie” was being investigated.

Kelly made up his mind early on. He clings to that childhood conclusion whenever the debate arises. The unthinkable. It still flares in Winchelsea, sometimes after a few drinks. How could it not?

FARQUHARSON TO MEET LAWYERS OVER EX-WIFE’S COMPENSATION BID

FARQUHARSON HAD NO INTEREST IN SAVING HIS KIDS

Once this town of 1300 was on the road to somewhere else — the dairy farms and graziers out west, or the beaches to the south. Then Winchelsea was blotted by the tragedy that can be neither avoided nor explained a decade later.

The reminders are everywhere. The scratched-out father’s name on the children’s grave. The fresh flowers on the little crosses at the roadside shrine. The tribute numberplate on the boys’ mother’s car.

The footy club remains a hub, like most country towns. There, some think this and some think that. This can be fraught — a point of view in Winchelsea is taking a side.

The star witness against Robert Farquharson used to be the club’s reserves coach and vice-president.

Kelly shies from the arguments in which gut feel and gossip can take precedence over forensics and legal admissibility. Jai’s mates are all circumspect. It’s simple enough, they explain — they miss their friend.

“Sort of sit on the fence,” says one, of the reasons for his friend’s death. “Let the adults take care of that one,” says another, now 20.

Kelly goes a titch further, with prodding. Others accepted Farquharson as a cleaner with a fondness for fish and chips.

Kelly knew an Auskick dad who cared for both his son and his mates.

Two juries have convicted Robert Farquharson: one of the judges spoke of a tragedy that “defies imagination”.

Outside pockets of Winchelsea, Farquharson’s accepted honorific is “evil”.

Perhaps because of Farquharson’s marathon of appeals, which ended only in 2013, the death of his boys still seems fresh. Farquharson is still fighting a compensation claim from the boys’ mother, Cindy Gambino.

He will be in his 70s when he is released for murdering those most dear. Yet Kelly still speaks of “the accident”.

Dawn Waite witnessed Farquharson’s 1989 Commodore hurtle off the road. She didn’t know this at the time. She thought the lights she glimpsed in her rearview mirror were turning off the Princes Highway into a driveway or side street. She drove home to her dairy farm east of Warrnambool, her 16-year-old daughter and a friend in the back, singing songs after shopping at Chadstone.

Waite now avoids the road.

“I cannot drive past those little crosses without thinking about it,” she says. “I think about it a lot.” Last year, Waite confronted the cheeriness of those hours, and how it jarred with the chaos she drove from. She picked up Helen Garner’s magisterial work, This House of Grief. Then she put it down again.

“When I read the first part where Robert had gone to Cindy’s place and the events ... that was me done,” she says.

She’s referring to one of many small decisions that day, September 4, 2005, that don’t make a lot of sense. Again and again, she sighs “it’s so sad, it’s so sad”, as if the lament must suffice in the absence of explanation.

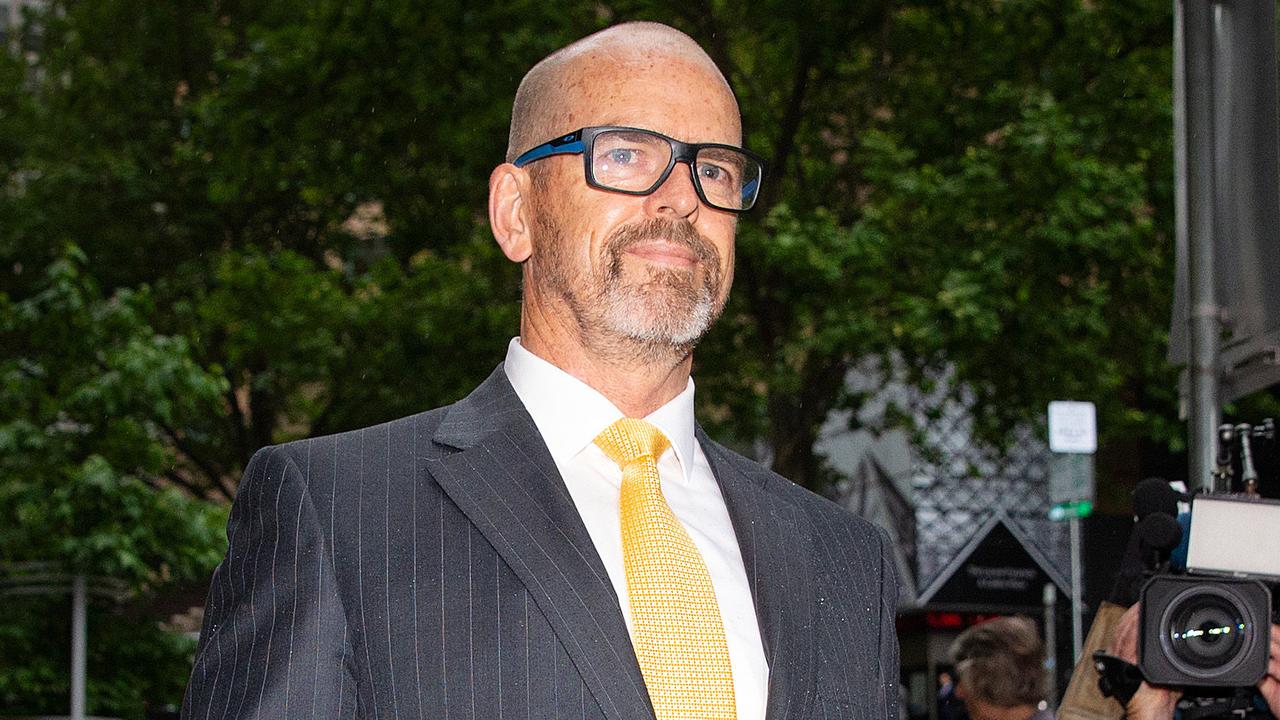

Retired policeman Jeff Smith was a senior-sergeant with the major collision investigation unit 10 years ago.

He was at the dam that night, seeking answers from the soaked man with the muddied face.

In a long career, Smith poked through the remains of the Kerang train and Burnley Tunnel crashes. Getting into Farquharson’s car at the dam’s edge was “the worst thing I’ve ever done”.

“I can picture them now,” he says. “They were three innocent kids and it wasn’t right.”

Smith interviewed Farquharson at Geelong Hospital. Farquharson’s odd priorities during that chat would become a prime focus in subsequent years of legal wrangling. He seemed resigned instead of anguished.

As someone close to his cause says, he failed the “Dad Test”. If his kids had to die, why hadn’t Farquharson shown a willingness to die in their rescue?

Smith says he scribbled notes that led to a simple question — deliberate act or accident? He jotted more than 10 reasons that pointed to intent. Under “accident”, Smith listed only one.

“That one reason was that no one could be that evil,” he says. “We always thought that the hardest thing about convicting him would be getting people to believe anyone could be that evil.”

Yet broader details tend to smudge rather than support either theory.

Farquharson only had the children at all at the time because of a last-minute offer from their mother to take them to dinner. His friend Michael Hart also gave evidence in 2010 that appeared to muddle notions of premeditation.

The Winchelsea builder said he was invited on what would be the fateful car ride that night. Hart says Farquharson was “adamant” that he and his son come for KFC in Geelong.

Farquharson had been coughing for weeks. He would blame cough syncope — a coughing fit that leads to a blackout — for careering off the road about 5km from Winchelsea.

He was driving the “s--- car”, as he was said to call it, after a splitting of assets with Gambino. “I asked him the day after and he swears black and blue it was an accident,” Hart says. “Murderers are selfish bastards — he wasn’t selfish like that.”

Farquharson had been openly resentful of arrangements with his ex-wife, and had just been told that his child support payments would rise. He had recently told a friend he would pay his ex-wife “back big time”.

Farquharson woke in the water, according to his story. “Hold on, hold on, I’ll get you out,” he apparently told his kids. Water rushed in after one of the boys opened a door.

He did not unbuckle the kids’ seatbelts. After he got out, and the car sank, he “went into some kind of shock or something”. He dived down three or four times, or so he thought. “I had two arms, two legs,” he told police. “How was I supposed to save three?”

He flagged down passers-by. “I’ve killed the kids,” he said. “What the f--- have I done?”

He declined their offers to dive into the dam or ring for help. Farquharson wanted to go to his ex-wife’s house.

Police swarmed the scene as Farquharson begged cigarettes and looked on. He projected the concern, said his frantic ex-wife, of someone who had lost a pushbike.

By morning, the police had pasted the road with yellow arrows. These would plot a course through grass and past a tree. The police concluded that the car was steered.

At hospital, Farquharson had not inquired about his kids. Told they had died, he said: “Ah, I gathered that.”

“He said ‘what’s the scenario for me?’ ” Smith now recalls. “The only questions he asked were about his own welfare.”

Dawn Waite did not report her observations for more than four years. She fretted at the thought of her daughter on the witness stand. By the time of Farquharson’s first trial, Waite was getting weaker by the day: a subsequent cancer diagnosis led to intensive chemotherapy.

She had trailed Farquharson’s car before its plunge. He was driving about 60km/h and the car wandered, as if the driver was “looking for foxes” on the road’s edge. “I know he wasn’t coughing when I passed him,” she says. “He slowed down just before the bridge and pulled over so that I could pass.”

Going to police in 2009 — after Farquharson’s first trial verdict was put aside — was “the hardest thing”, she said. She braced to be judged: “The worst thing that I had to deal with was Robert’s sister looking at me as though I was an absolute piece of dirt.”

Waite dropped herself into a vortex where the sinister, once again, got tangled in the absurd. The so-called “fish and chip” conversation would again feature. Greg King said that Farquharson had told him he would kill his children — in a dam, on Father’s Day — so that Gambino would suffer.

King’s shows of trauma and frustration — ultimately, his evidence would be put aside — would embody the fractures of a community. He elected last week not to comment, reflecting a wider preference for silence.

The second time around, Cindy Gambino had shifted.

She had believed in her husband previously: she wore a “facts before theory” badge to the first trial. After that verdict, she left the court in an ambulance.

The second trial was different. “This is not The Oprah Winfrey Show,” defence lawyer Peter Morrissey told jurors. He swelled in the courtroom, Farquharson shrunk. The man he called “Robbie” on the stand looked lost both in and out of the court: Garner wrote of Farquharson’s sister leading him across the road in a “bossy big-sister grip”. A police source describes the courtroom tension as “poisonous”.

Police had carried out reconstructions under various speed and steering scenarios.

When the test driver let go of the wheel, the car stayed on the road or veered to the left — the other side of the road to the dam.

Sen-Constable Glen Urquhart gave evidence that Farquharson’s car took a sharp right off the road — more than a half turn of the wheel — steered straight through grass, then veered right to avoid a tree. The tests pointed to three distinct “steering inputs”.

The defence did its own tests. Morrissey asked if the police tests were a “disaster”.

The defence had unsuccessfully appealed against the police’s evidence in the first trial. This time, Morrissey asked Urquhart: “Can I just put it to you, it’s just tunnel vision by you, just looking for things that you think might make him look guilty?”

Farquharson was called to tell his story. Morrissey couched his client’s introduction in the effects of trauma. Years earlier, Morrissey had defended a Bosnian military commander against charges of mass killings at the International Criminal Tribunal.

There, he heard of parents who stood by as their children were massacred. Shock and survival mode are unknown qualities until tested.

“We all know what we should do, but unless you are there you just don’t know,” Morrissey now says.

Farquharson’s body language was convincing enough. He clasped his hands under his paunch and wiped them on his pants. He choked when asked about the presents he received from his kids on the day they died. Yet he sounded vague. He wished he had done more, he agreed. Two jurors looked away throughout his evidence, a traditional show of disbelief.

Farquharson was uncertain about events after the car hit the water. Parental instinct demanded he recall every tortured instant.

His ex-wife could. Gambino blazed in purple, down to her hair. She screwed up a photo of her ex-husband. She had to be excused as her 000 call that night was aired. “You disgust me,” she replied to Morrissey’s inquiry about the headstone.

Gambino no longer believed, she explained in detail to a defence lawyer who seemingly did. She seethed as Morrissey parried. He sounded like he wanted to understand but never would.

What of her media proclamations of his innocence, he wondered. Had she been medically advised to apportion blame? She credited Waite, calling her a “big piece of the puzzle”.

Morrissey’s examination had to be stopped for comfort breaks. Gambino crumbled when footage of her boys in the bath was accidentally aired. Justice Lasry — who has in vain defended prisoners condemned to death — said Gambino’s three days of evidence may have been the most harrowing of his career.

Afterwards, Morrissey asked that Gambino be removed. She had sobbed and wailed and her cries, likened to a wounded animal, still haunt observers and Morrissey argued her continued distress could influence the jury.

When the case was over, Morrissey stood outside the Supreme Court and vowed to appeal. He was shaking, as if he was as traumatised as anyone in the witness box.

Some days, Cindy Gambino does not rise until noon. She takes pills for depression, sleep and nausea. The drugs and dosages are often adjusted.

You “intended her to live a life of suffering”, said Justice Philip Cummins in sentencing Farquharson to three life terms in 2007. “He hasn’t messed up my life, he has shattered it into little pieces,” she said recently. Gambino struggles to brush her hair or go out. She says she sits on the couch, sees no one and does nothing. She plays a loop of what-ifs. What if she had not left Farquharson? What if she had given him “the good car”?

“Since that day, every day has been the same,” she says.

“Everything is hard.”

Gambino hits Facebook and offers heartfelt expressions of thanks to husband Stephen Moules and friends. In June, she vented: “I hate that bastard who did this to me. I hope he is suffering.”

A few years ago, Gambino had an accident near the little crosses at the dam, a memorial that is now — after her lobbying — tucked behind a guard rail. She revealed a mother’s need to be near her boys in a victim impact statement in 2010. Sometimes she slept next to her boys’ headstone at the Winchelsea Cemetery. She said she asked her sons for help.

There are so many triggers. Gambino stayed in bed for a week when Darcey Freeman fell from the West Gate Bridge in 2009. The photo used in most media stories is the same one she framed for the boys to give to their father on the day they died.

She took up with Moules after her marriage breakdown. They have two sons, Hezekiah and Isaiah. Not long ago, the boys were playing with toy cars in the bath and one said: “Look Mum, the car sinks.”

The pain is undimmed. “We don’t know what each day will bring,” Moules says. “We take each day as it comes.”

Jai Farquharson’s closest friends gathered around a pot-bellied stove last week.

They planned to gather at his grave in October for what would have been his 21st birthday and “have a beer with him”. They spoke of the boy he was and the man he would have been. Smiling, they figured, and stubborn.

Jai will always be the kid who rode his bike around town with his mates. They took turns to buy chips and soft drink. They leapt from a tree into the river in summer.

They’re all grown up now. They’re builders and labourers and students. Perhaps Jai would have been the fireman he hoped to be. He’d probably work outside, they reckon. He’d definitely play footy. “He loved footy more than all of us,” says Tavae Sauni.

Instead, the story of Jai and his brothers stopped at a dam and bled into their father’s. Their smiles are hidden behind yellow buds that dance in the wind of passing cars. Scrub grows wild here, yet the site itself is regularly tidied by a proud grandfather.

“Jai would be 21 and he could have been married,” Bob Gambino says. “But they were just kids — they change their mind all the time.”

Jai is remembered more fondly than his father at the same age. A local elder recalls Robert Farquharson as a skinny kid, the youngest of four. “In his early years he was a rather spoiled child,” he says.

“He liked to get his own way and usually got it.”

Hart spoke with Farquharson a few years back, in between trials and after Farquharson had spent time in jail. Hart’s mate seemed altered. He swore a lot and flinched when touched.

Hart asked him if he was the person he had always been. Farquharson replied: “How can I be the same bloke?”