Burwood Triple Murders: Motive for Ashley Coulston's chilling killings still baffles

THEY were random victims — three young people set on a collision course with a deadly stranger by an innocent ad for a housemate. Just weeks after the chilling killings, the cold-blooded murderer was ready to strike again, only to be thwarted by exceptional acts of bravery.

True Crime Scene

Don't miss out on the headlines from True Crime Scene. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Murder in Suburbia by Emily Webb features the stories of more than 20 murder cases in the quiet streets of Australia’s suburbs and small towns. Among the most disturbing is the case of Burwood triple killer Ashley Mervyn Coulston.

——————————————

An innocent classified advertisement in a Melbourne newspaper by students seeking a housemate led to one of the most cold-blooded murders the state of Victoria has ever seen. The perpetrator was a man named Ashley Mervyn Coulston.

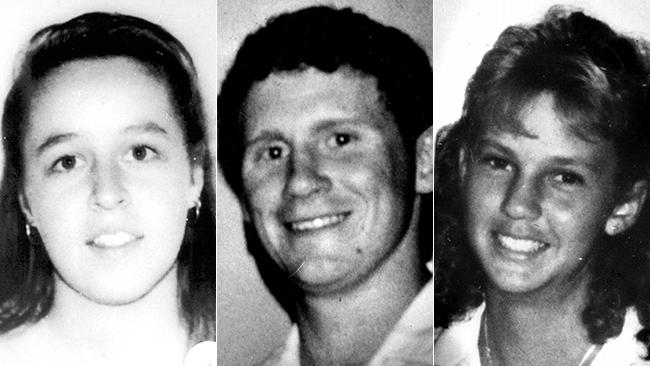

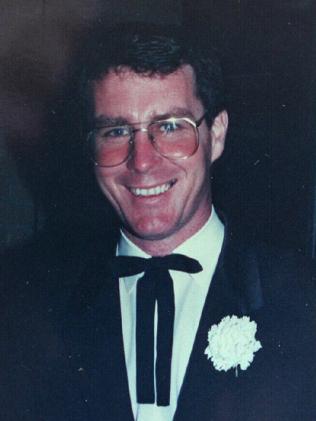

Not many Victorians who were old enough at the time will forget the crime known as the ‘Burwood Triple Murders’. On 29 July 1992, the lives of three young people – student teachers Kerryn Henstridge and Anne Smerdon, both 22 years old, and Anne’s brother-in-law Peter Dempsey, 27 – were snuffed out in a bloody execution in their share house in Summit Road, Burwood. Burwood is an eastern suburb of Melbourne – quiet, established, very middle-class and often perceived as a stale suburb with very little life about it. It was certainly a most unlikely setting for a crime so shocking.

Anne and Kerryn were student teachers and knew each other from university. For the girls, both from country Victoria (Anne was from Kyabram and Kerryn from Hamilton), the Summit Road house was just minutes away from Deakin University where Kerryn was doing the fourth year of her Bachelor of Education. Peter, a Telecom engineer who lived in the large rural town of Shepparton, was visiting at the house that night. He regularly stayed at the Summit Road house while attending training courses for his work. The third regular tenant, a man in his twenties, also from Hamilton, was away visiting his family. On the evening of 29 July 1992, the girls were expecting a caller to interview as a possible replacement for Kerryn, who was due to move back to Hamilton the next day. She had the opportunity to return to her hometown with her mother that night but had elected to stay until a tenant was found and the bond sorted out. Her mother, Jeanet, was staying with a family friend a few doors away in Summit Road. Several people had answered the advertisement, including a ‘Duncan’, who had said he had recently moved from interstate and had asked, ‘I’m 40 years old, is that a problem?’ There was even a note by the telephone, written by Kerryn on the night of the murders: ‘Anne, Duncan is coming over tonight. Don’t worry, someone will be home. Kerryn.’

It is quite possible that this Duncan could have been Coulston, but what is known is that more than one stranger was expected at the Summit Road house that Wednesday evening. One potential housemate, a young man, turned up at 8 p.m. sharp to take a look at the place. He told police that he left after 10 minutes, with the women telling him they would be in touch about the room. This is the last time the three were seen alive.

It is almost certain that Coulston had read and telephoned in response to the advertisement. Using a Melway street directory (Coulston’s thumbprint was later found on the page that included Summit Road), he drove for over an hour from his Westernport Marina home in Hastings, more than 60 kilometres away, to Burwood, arriving at the house after 8.30 p.m.

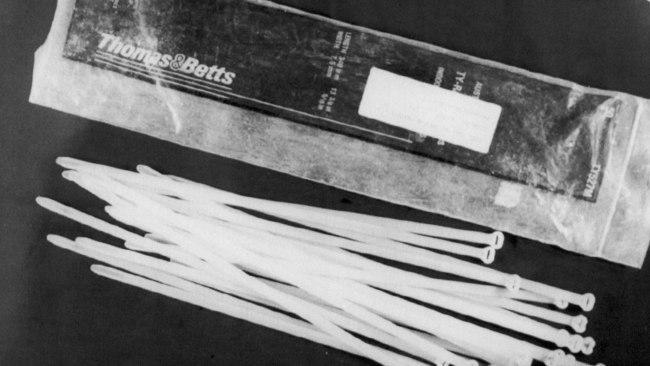

No-one except Coulston, then aged 35, and his victims know what happened that night before the unfathomable and brutal execution. To this day, Coulston has never uttered a word about the crimes. He answered ‘no comment’ during the police interviews about the murders at Summit Road and stood mute during his trial. Coulston went to the Burwood house with a bag containing a .22 rifle, a silencer, ammunition and plastic cable ties. He bound, gagged and covered the heads of the three occupants, each in separate areas of the house, and then shot them at close range.

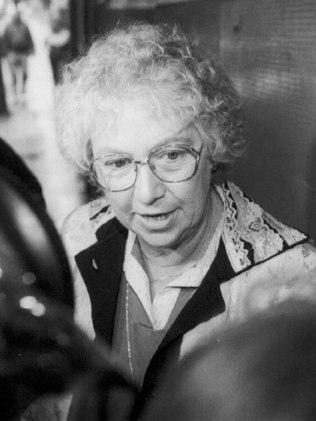

It was Kerryn Henstridge’s mother who found the trio dead the next morning. Kerryn was supposed to meet her mother at the family friend’s home, in the same street, where her mother was staying. When she didn’t arrive, Mrs Henstridge became worried and went to the share house. When there was no answer when she knocked at the door, Mrs Henstridge climbed through a window and discovered her daughter’s body facedown on the floor. For anyone, let alone a parent, the thought of what Mrs Henstridge discovered that morning is unimaginable.

News of the triple murders hit the media and the photos of the three smiling, young victims with all the promise in the world made the front pages of both the Herald Sun and The Age. The crime shocked Victorians. For one, it was a chilling, cold-blooded execution that seemed to be out of a Hollywood movie, rather than the quiet suburban streets of Burwood. Secondly, there seemed to be no motive for the killings. Police were baffled and worked around the clock for a breakthrough in the case. The victims were all clean-living young country people with no records or association with the criminal world. The killer took around $200 from the house but police did not believe that robbery was the motive. Another motive explored was that someone was infatuated with one of the girls.

There was also the possibility that the house was picked at random (this turned out to be the chilling truth) but with no solid leads in the weeks after the murders, police turned to the media to appeal for any information that could crack the case. Almost daily there were newspaper reports, and the public followed the case closely. The fact that there was a cold-blooded killer who had targeted a home in a respectable suburb of Melbourne’s east filled many with dread and there were real fears from the police that the killer could strike again.

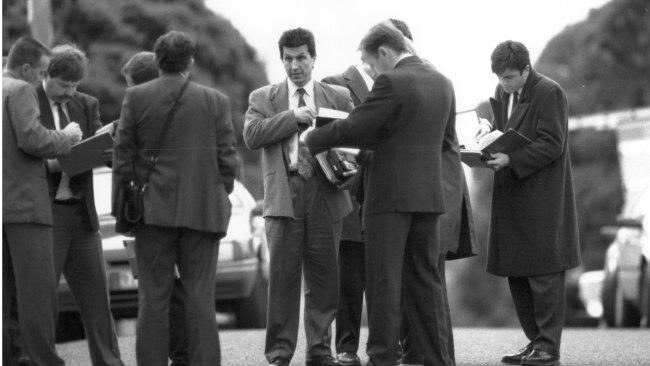

The Homicide Squad questioned more than 400 people who advertised for a housemate in the week before the murders and wanted to know if anyone who answered the ads had seemed suspicious or had acted strangely. High-profile crimes tend to attract people who want attention and false leads provided by a man who contacted investigators several times frustrated them. It wasted precious resources and time and the man was charged with giving false information to police. A police caravan was set up outside the house in the hope that people could give them some fresh leads and the devastated families of the three victims gave heart-wrenching pleas for help.

The wife of victim Peter Dempsey, Liz, begged the public for help. Married just three years to her sweetheart, Liz said, ‘Life’s just been ruined.’ She lost her husband and sister in the evil act. Peter Dempsey’s father Frank said the term ‘animal’ was too good for the killer.

FOLLOW: True Crime Australia on Facebook and Twitter

The breakthrough for police came five weeks after the murders. At 8.45 p.m. on 1 September 1992, married couple Richard and Anne Shalagin arrived at their car, parked at Government House Drive opposite the National Gallery in St Kilda Road, where they had attended a function. As they got in the car to drive back to their Coburg home, the couple were surprised by a balaclavaclad man who terrifyingly and silently pointed a gun at them. The couple assumed that the lone gunman wanted money and thrust a few $50 notes at him in the hope that he would disappear. He grabbed the money but did not leave as the frightened couple had hoped. The gunman forced the Shalagins from the car at rifle-point and motioned for them to go to a darker area under a large tree. He told Anne to lie facedown on the ground, kicking her even as she complied. Taking a long, cream plastic cable tie, the man was about to bind Anne’s hands. Richard Shalagin, who would later tell the Supreme Court of Victoria that he had no doubt he and his wife would die if they further obeyed the assailant’s instructions, quickly noticed that the man had put his rifle down, and he seized his chance to instinctively leap and attack. Richard grabbed the man in a bear hug and snatched at the gun, yelling at his wife to ‘run’. Richard was bitten on the hand by the man as he held him from behind. Anne ran away, screaming, and Richard broke away from his attacker and followed his wife. Hearts thumping and adrenaline racing, the Shalagins literally ran for their lives towards busy St Kilda Road.

The couple’s understandably hysterical screams were noticed by two security guards, Paul Sycam and Graeme Loader, who radioed for police help. According to court reports, Mrs Shalagin warned two nearby people, ‘Don’t go, he’s got a gun. He’s tried to shoot us.’ The security guards approached the man, who pulled a knife on the pair. Mr Sycam later told the court that he then saw the man crouch down and hold a sawn-off firearm at waist level. The armed assailant shot at the two men five times. Mr Sycam said he heard the first shot zing past the right side of his head. He then described how he felt a shot to his hip and despite this ran after the shooter. Mr Sycam tackled him from behind, punching and kicking him. Police had arrived at the scene quickly and they arrested the gunman and took him to a nearby police station to be interviewed.

The man was Ashley Mervyn Coulston, and he was found to be in possession of ‘chilling accessories’ in his bag that night – a filter, a knife, a balaclava, high-velocity .22 cartridges, handcuffs, thumbcuffs and plastic cable ties. The Shalagins had been extremely lucky. The actions taken by Richard and the security guards that night, described as ‘brave, almost foolhardy’ by Justice Bernard Teague at Coulston’s 1993 sentencing, saved their lives. Ballistic tests had revealed that the shotgun used to menace the Shalagins was the same one used to murder the three young people in Burwood. It was the gun that held the key to nailing Coulston for the murders. Forensics conducted by Victoria Police showed that the bullets recovered from two of the Burwood victims had been discharged from the firearm found in Coulston’s possession (a third bullet was too badly damaged to be examined). A forensic scientist found a high-velocity blood spatter on the dressing gown found over Anne Smerdon’s head matched the bloodstains on the oil filter, which had been fashioned into a silencer for the rifle.

A few days after his ‘no comment’ interview about the Burwood murders, Coulston spoke to a police officer, in the presence of his solicitor, about the rifle. Coulston told police that in the week before the murders, a sailing friend named ‘Rod Davis’ had asked for a loan of the rifle and asked him to shorten the barrel. Coulston said the gun was returned to his car boot. The man whom Coulston alleged had borrowed his weapon was an America’s Cup yachtsman Roderick Davis, who was called to give evidence at Coulston’s trial. Davis testified that he had been competing for New Zealand at the Barcelona Olympics when the three people were murdered and that he did not know Coulston.

Coulston maintained his story that he was visiting his partner Jan McLeod at Frankston Hospital on the night of 29 July. Ms McLeod backed up Coulston’s story in court and said that he had not left her side between 8 p.m. and 9.15 p.m. that night, despite witnesses seeing him at 7.50 p.m. and 10.30 p.m. at the marina in Hastings where they lived on her yacht.

Police were left frustrated by Coulston’s refusal to answer questions about what happened at Summit Road. Here was a man who seemed of normal intelligence, who on the face of it, functioned in society and was in a relationship, yet had committed this random act of extreme violence. Coulston just didn’t make sense and they had to rely on his family history and expert analysis to try and find out what made him tick.

The sickening crimes were not the first time Coulston had come to the attention of the public. In 1988 he made headlines but for entirely different reasons. It was Australia’s Bicentenary year and Coulston wanted to make his mark on history. His contribution was to attempt to sail the smallest boat across the Tasman to New Zealand. He painstakingly spent almost a year designing and building a 2.5-metre-long aluminium yacht, roughly the size of a spa bath with the moniker G’day 88. It was a daring feat by anyone’s standards and while he was thwarted on his first attempt by a cyclone (he embarked from Sydney on Australia Day and was rescued by a tanker 46 days later), his second attempt at making a piece of history was a success when he sailed the tiny sailboat to Brisbane from New Zealand, landing on shore on 6 January 1989. His adventure was celebrated in an Australian Geographic spread and newspaper reports and he was dubbed ‘Captain Bathtub’.

Like his young victims, Coulston was from the country and lived on a dairy farm in the town of Tangambalanga in Victoria’s Kiewa Valley. Born on 10 October 1956, he had a brother and two sisters and grew up in a loving family, despite his mother’s chronic ill health that meant she had long spells in hospital. It was also reported by old school friends that Coulston was dyslexic and struggled at school. Described as shy, secretive and a loner, Coulston ran into troubles in his early teens, starting with robbing the local butter factory when he was 13 and burgling other buildings in the town.

It was a shocking incident when Coulston was 14 that gave a glimmer of the violence that would lie ahead. On 19 April 1971, after two weeks of stalking two young female teachers, he broke into their house beside the tiny Kiewa school and abducted the women, both aged 22. As with his future crimes, Coulston armed himself with a .22 rifle. At gunpoint, he forced the two terrified women to drive him interstate into New South Wales, towards Sydney.

At 5 a.m. the next day, the trio stopped at a Gundagai roadhouse to get some food. The teachers started screaming for help, which alerted a truck driver to their plight and they were rescued.

Coulston moved back to the family farm and then moved with his family to a new farm in northern New South Wales. Coulston’s father retired the following year and in the early 1980s the family moved to Queensland, where Mr Coulston felt the weather would be better for his ill wife.

In his mid-twenties, Coulston moved back to NSW and had several jobs, including one at Hertz Rent-a-Car. An unnamed man told the Sunday Herald Sun that Coulston had to leave his Hertz job after a female colleague made complaints to the management. The woman provided evidence to police for Coulston’s later committal hearing and told officers that after she had declined Coulston’s invitations for dates, she noticed that he had been following her as she went to and from work.

Coulston had become more interested in sailing, the hobby that would bring him some national recognition. Sailing also introduced him to Jan McLeod, a woman more than 15 years his senior, and the pair struck up a relationship and eventually moved in together in Ms McLeod’s yacht, moored at Hastings in Melbourne. Coulston’s trial began in late August 1993 at Victoria’s Supreme Court and ran for almost a month. At Coulston’s eight-day committal hearing at the Melbourne Magistrate’s Court in January 1993, the court was told of his abduction of the two teachers in 1971 and also of the incident at Hertz with his female colleague. It was also noted that the Hertz employee, one of the teachers Coulston abducted and Anne Smerdon all had shoulder-length blonde hair in common. It was not proven whether this had anything to do with Coulston’s motives, but it was a discussion point.

Coulston was tried for the Burwood murders and 11 other charges over the incident in St Kilda Road, including attempted murder of the security guards, the armed robbery of the Shalagins and resisting arrest. He pleaded not guilty to all charges. The case was tried in front of Justice Bernard Teague. Prosecutor Ross Ray said in court that it was difficult ‘to conceive of a more frightening, random or more cold-blooded execution of three innocent victims . . . who are not known to the prisoner’. A Pentridge prisoner gave evidence that in several conversations he and Coulston had, Coulston had admitted to ‘killing the kids’ and had said that his biggest mistake was not getting rid of the gun. The prisoner, a convicted armed robber, said he told Coulston that his biggest mistake was the murder, to which Coulston replied, ‘Yeah, I’m sorry.’

Coulston’s partner Jan McLeod told the court that he was with her at Frankston Hospital until 9.15 p.m., where she had throat surgery, on the night of the killings.

Justice Teague made many poignant statements in his sentencing remarks. When handing down the three life sentences with a minimum of 30 years on 21 September 1993, Justice Teague remarked:

You appeared from out of the night. You invaded a typical suburban home. You executed three victims. You disappeared into the night . . . the seasons of your life left to you will scarce allow for more feats of fame or notoriety. But you have made for the beloved of the three you killed an enduring winter. And for the three, there are no more seasons.

Ms McLeod vowed to do whatever it took to clear her lover’s name, describing Coulston as the ‘dearest man I have ever known’. She told a newspaper that Coulston was in good spirits when she visited him because ‘he knows we’ll be out here fighting’ for his release.

In 1995, Coulston was granted a retrial with the three murder convictions quashed on appeal. Coulston’s lawyers made the successful appeal based on evidence at his first trial that related to the armed robbery that led to his arrest. The Supreme Court found that some of the evidence relating to the attack on the Shalagins was inadmissible during the first joint trial for the Burwood murders and the offences at St Kilda Road. The appeal judges said the suggestion of a similarity between the two incidents ‘might well have a beguiling appeal to the jury’. In the first trial Coulston was acquitted of the attempted murder of the security guards but guilty of the armed robbery of the Shalagins, false imprisonment, intentionally causing injury, assault and using a firearm to resist arrest. The Supreme Court set a two-year minimum sentence for the St Kilda Road charges and said Coulston should have been granted a separate trial on these charges.

During the second trial that ran through August and early September 1995, Coulston’s lawyers attacked the credibility of the officer who had performed the ballistics testing on the gun. Victoria Police Leading Senior Constable Ray Vincent was a ballistics expert and was on duty on both nights of Coulston’s crimes. When he attended the St Kilda Road scene, he noticed the plastic ties and recalled that they were the same brand left by the killer at the Summit Road murder scene. When the bullets from the firearm were compared to bullets found at the Burwood scene, they were found to be a match.

Supreme Court judge Mr Justice Norman O’Bryan made specific reference to the attack Coulston’s defence made on the professional reputation of Senior Constable Vincent, the main prosecution witness, during the second trial. Coulston’s defence alleged that Vincent had actually substituted three different bullets for the ones taken from the Burwood victims, so that he could say in court that the weapon found on the accused at St Kilda Road was the murder weapon. The defence used private forensic investigator Bob Barnes as their expert witness. Mr Barnes had been dismissed from the Victorian Forensic Science Centre for ‘scientific misconduct’ in 1993, though the defence did not know this at the time.

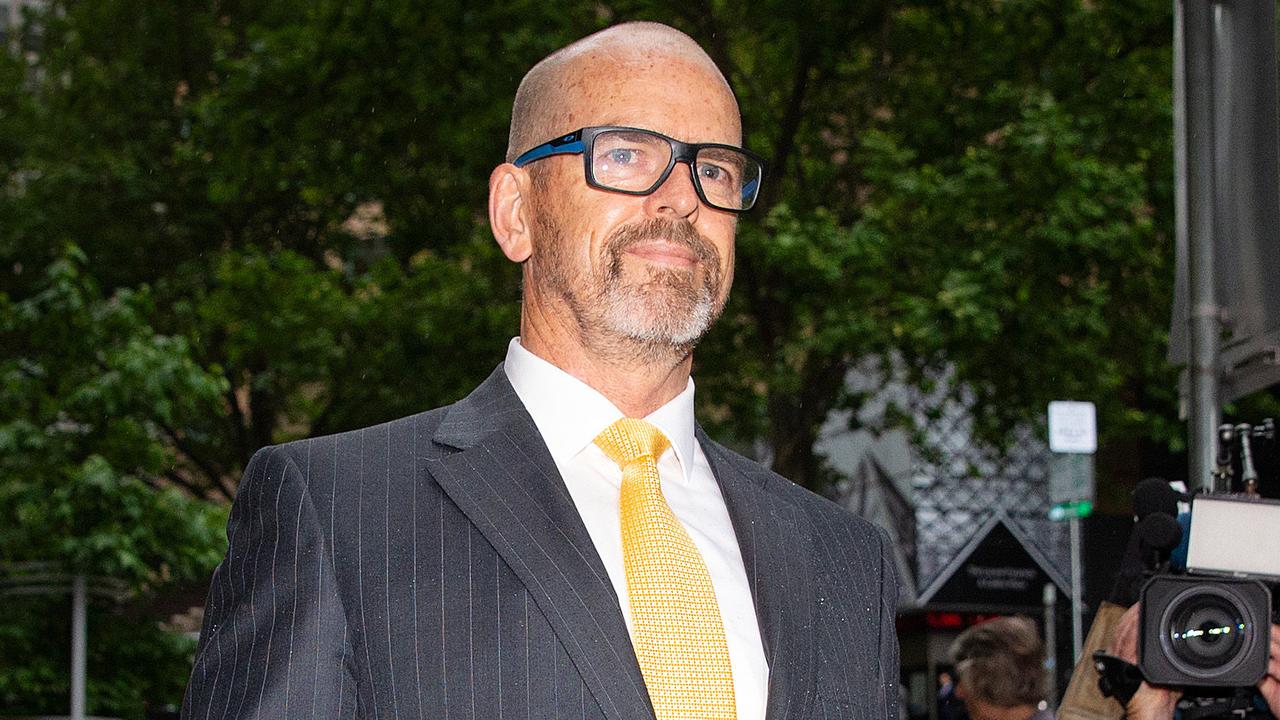

Coulston was again found guilty of the three murders in Burwood and Mr Justice O’Bryan said ‘the wicked nature’ of his offences gave the court the power to give him a life sentence with no minimum. Coulston would be imprisoned for the term of his natural life. Mr Justice O’Bryan mentioned the case of Frankston serial killer Paul Denyer when sentencing Coulston. In 1993, the then 21-year-old Denyer murdered Elizabeth Stevens, 18, new mum Debbie Fream, 22, and Natalie Russell, 17, in and around the Melbourne bayside suburb of Frankston. In 1994, Denyer, who now lives as a woman in prison and refers to himself as ‘Paula’ appealed his life sentence successfully and was granted a non-parole period of 30 years. However, Mr Justice O’Bryan remarked: The fixing of a non-parole period is mandatory unless the nature of the offence or past history of the offender make the fixing of such a period inappropriate. Taking into account the wicked nature of these crimes and the absence of remorse of any kind on your part, I shall not fix a non-parole period. He also noted that Coulston ‘stood mute’ during this second trial, as he did in his first. Mr Justice O’Bryan said it was his belief that Coulston’s fear of self-incrimination was the reason and that he had ‘forfeited forever’ his right to live outside the confines of prison. ‘I am of the opinion that you should never be released,’ Mr Justice O’Bryan said.

Coulston would not give up though and challenged his sentence with a second appeal in 1996, which failed at the Court of Appeal. An application to the High Court for special leave to appeal against his conviction also failed in late 1996. He had exhausted his last legal avenue and the families of the three murdered in Burwood did not have to endure more painful court appearances.

Outside the High Court on 13 December 1996, Rob Henstridge, Kerryn’s father, said the families would be forever hurt over the lack of explanation or apparent motive Coulston had for the murders. The pain for them would go on, their lives forever changed by Coulston’s cold-blooded actions.

‘There is no explanation and we’re never likely to hear one. We just don’t know and we’ll never know and that’s what really hurts,’ Mr Henstridge said.

Coulston baffled even Australia’s best criminal psychologists and criminal profilers. Melbourne-based forensic psychologist Ian Joblin told Herald Sun journalist Russell Robinson that the Burwood triple killer perplexed him. In a 2005 interview with Robinson, Dr Joblin, who spent hours assessing Coulston, said he couldn’t find a motive for the killings. ‘In terms of trying to resolve the conflict between [Coulston’s] presentation and the offending, it’s the most perplexing one,’ Dr Joblin said.

Coulston has not stopped trying to prove that he is innocent. In a 1998 incident that forced the State Government of Victoria to re-examine its Freedom of Information (FOI) law, Coulston was able to obtain the names of 51 nurses who worked at Frankston Hospital in 1992 so that he could establish his alibi for the night of the triple murder and get the case reopened. Coulston and his partner Ms McLeod had always maintained that he was visiting her in hospital at the time the killer struck at Burwood. The hospital’s management initially knocked back two FOI requests by Coulston but the killer appealed to the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal (VCAT) who upheld his appeal. The Australian Nursing Federation and the then premier Jeff Kennett slammed the actions of the hospital and said it had been incompetent in not protecting the privacy of its staff. Newspapers grabbed hold of the story and readers were shocked to read that the hospital had no legal representation at the first appeal hearing and that Coulston had represented himself via video link to plead his case for access to the names. The fact that Coulston’s legal challenges were being paid for by the taxpayer was also infuriating for Victorians. Premier Kennett received a letter from Coulston in early 1999, in which the prisoner assured him that he would not misuse the names of the nurses.

Premier Kennett used the incident as the means to change the Victorian FOI laws to ensure that public sector workers’ names would not be released if there was a threat to a person’s safety. Chillingly, one newspaper even reported that Coulston was believed to have used the laws and applied to the State Coroner for access to homicide files in the Mr Cruel Case. The still unsolved Mr Cruel case involved the abduction and sexual assault of at least three schoolgirls from Melbourne’s eastern suburbs. One girl, 13-year-old Karmein Chan, was found murdered – shot execution-style in the head – one year after she was abducted from her parents’ Templestowe home. The identity of Mr Cruel is one of Australia’s most notorious and haunting crime mysteries and at one stage, police considered that Coulston might have been the perpetrator.

Coulston was also investigated at one time over the murder of Sarah McDiarmid, 23, who was kidnapped from Kananook railway station in Melbourne in 1990. Her body has never been found and the cold case has baffled police for years. Eventually, no evidence was found to link Coulston to Ms McDiarmid’s death.

Cold case vow: Police will never stop hunting Sarah McDiarmid's killer

Is it possible that the three young victims in Burwood were the only people Coulston has murdered? Of course, it is most likely that the night Coulston was caught by police he had intended to murder the couple in the gardens near St Kilda Road, but could he have kept his dark desires suppressed between the abduction of his teachers in 1971 and the 1992 Burwood murders? Some investigators think not.

Coulston is in the frame for a series of unsolved rapes and at least one murder along eastern Australia. A man known as ‘the Balaclava Killer’ began a reign of terror on the Gold Coast and Tweed Heads in the summer of 1979–80. Coulston was living with his family in Kyogle, NSW, close to the Queensland border. A masked man at Tweed Heads abducted an English man, Geoffrey Parkinson, 33, with a female friend on 2 February 1980. Parkinson grappled with the masked man and was shot dead with a .22 rifle. Coulston is also suspected of being ‘the Sutherland Rapist’, who attacked women between 1981 and 1984 in Sydney’s southern suburbs. This rapist wore a balaclava and carried a sawn-off firearm, just like the Balaclava Killer. Coulston was living in Sydney in the early 1980s. These crimes are still unsolved.

True Crime Australia: 'I nearly caught the Balaclava Killer'

Coulston’s crimes were planned meticulously yet his victims were chosen at random. His motives can only be speculated as the killer has remained silent all these years, but most believe he killed for thrills.

Coulston is now one of just a handful of prisoners in Victoria who are serving life sentences with no minimum – his crimes deemed so heinous that he will die in jail.

Ashley Mervyn Coulston is the stuff of nightmares but tragically for his victims and their loved ones, he is all too real.

This is an edited extract from Murder in Suburbia: Disturbing stories from Australia’s dark heart

The Five Mile Press Pty Ltd © Emily Webb, 2014

- This is an edited version of a story first published in June 2014