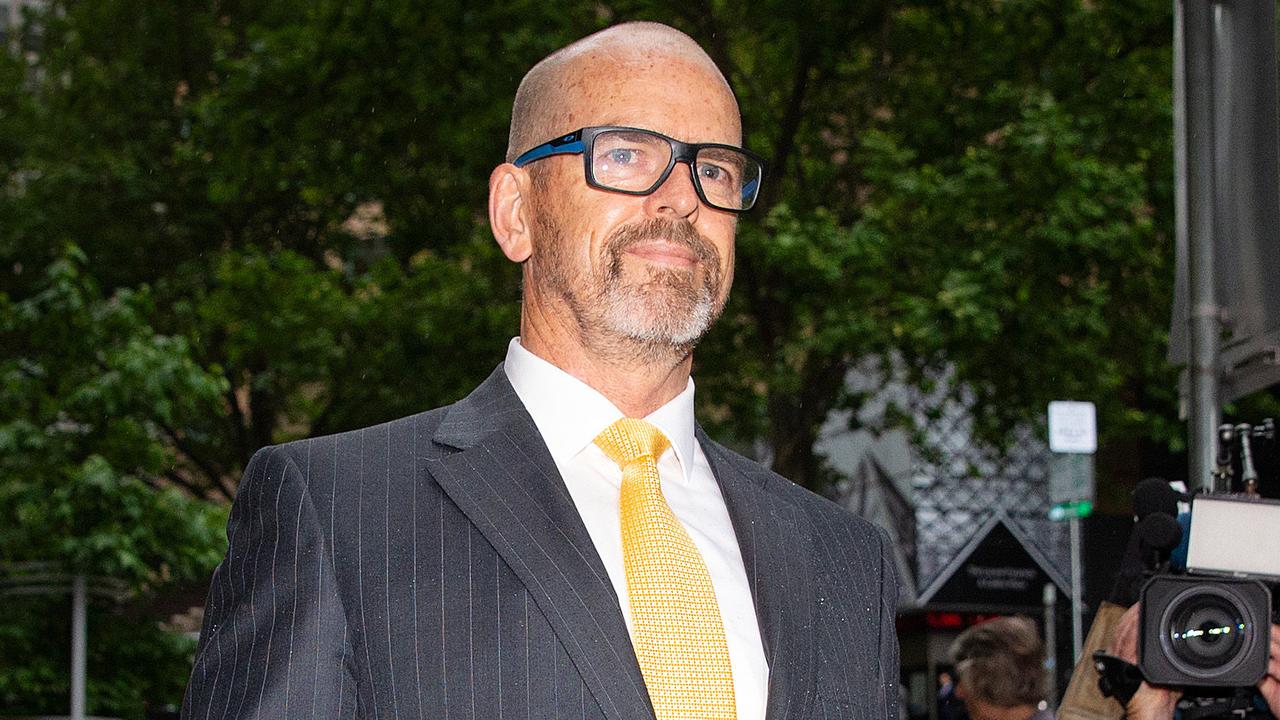

Paul Steven Haigh gave an insight into the warped mind of a mass murderer when he applied for a minimum jail term

VICTORIA’S worst killer Paul Steven Haigh has revealed his warped views on life, death, sex and religion ... and the fact he thinks a lot about fire.

True Crime Scene

Don't miss out on the headlines from True Crime Scene. Followed categories will be added to My News.

MASS murderer Paul Steven Haigh has some warped ideas about life, sex, religion and death.

A man convicted of murdering three men, three women and a young child, Haigh was recently described in the Supreme Court as “one of the few who should never be released again”.

Methodical and quietly-spoken, the greying Haigh is an institutionalised stone-cold mass killer with, it would appear, an underlying preoccupation with thoughts of fire.

He is Victoria’s worst who, like many mass killers with delusions of grandeur, has revealed insights into the working of his ruthless mind.

He did this by reading from his own existential ramblings during a failed Supreme Court bid for the right to a minimum jail term.

Those ramblings revealed a cold heart and self-centred mentality.

They proved Haigh lives on a barren emotionless plain foreign to decent human beings, and that he has a very high opinion of himself or just might fear what awaits him after death.

His criminal exploits began with theft of bicycles and cars and break ins and stealing and led to assault and escaping custody.

His murders weren’t motivated by passion, nor were they spur-of-the-moment mistakes.

They were committed out of selfish necessity.

He knows as much, but in the Supreme Court in December 2012 he spoke of having made “an amazing transformation”, like a grub to chrysalis to butterfly.

If in fact he had transformed into butterfly, albeit a drab and dirt-camouflaged kind, he flew too close to the sun and failed miserably in the Supreme Court during his application.

He revealed himself as a creature with no empathy or remorse.

“If parts or all of my personal journey of development are deemed eccentric, bizarre, demented, extreme, perverted or anything else, I respectfully submit that what is of ultimate importance is where it’s led me — and what I have become through my quest,” Haigh told Justice David Beach.

He also said: “I can only hope that when I eventually raise my eyes from (my explanatory writings) upon completion (of reading them to you), I won’t see loathing for me written on your face.

“It’s not my intention to step into your mind like a vandal who smashes and hacks at all you hold dear but if I’m to honestly communicate, you’ve got to properly consider my challenging notions.

“Laws change with time, as do people’s attitudes, including my own. If it wasn’t so, I wouldn’t be what I am today — a far cry from the monster of yesteryear.

“Society says I’m one thing and I say I am now something else, and if it seems I have no respect because I speak my mind, I have a great respect for the truth and none for anyone who schemes and lies in order to keep me behind bars.”

Haigh described his “honesty” and the “truth” about his despicable crimes as something that could make people recoil, like “a plate full of excrement that they must swallow and digest’’.

“(But) the Bible tells me that God speaks the truth, so it follows that if God is said to only do good, then speaking the truth must be a good thing,” Haigh prophecised from the dock.

LADIES UNDERWEAR: The case of the twisted killer colonel

INSIDE STORY: How a thief helped nab Oklahoma’s evil bomber

MELBOURNE’S MOST SHOCKING CRIMES: CBD | North | East | South | Peninsula

DEATH ON THE MENU: Gatto dodged a bullet, others didn’t

UNDERWORLD CONNECTION: Carl Williams and the Esky in the boot murder

THE BIKINI KILLER: Charming playboy left a trail of death

GIANT READ: How a Google search foiled tomato tin mafia’s multi-billion drug plot

Haigh told Justice Beach it was up to his victims’ loved ones to “move on’’ after the murders.

“People are responsible for overcoming their own hardships and tragedies,” the killer suggested.

“Owning fully the terrible and regrettable things I have done to mangle my victims’ lives and happiness, it is nevertheless up to them to move on.

“Unfortunately, there’s nothing I can do to help them and even if my atrocities have shattered them beyond repair all I can sensibly and logically do is repent, apologise and then keep working towards improving and preserving my own peace of mind and happiness.

“If my victims’ (relatives) aren’t interested in helping themselves, or they don’t have the mental capacity or wherewithal to do so, I must, regardless of being responsible for the crimes that ruined them, be self interested enough to make my own life as pleasant as possible.

“Not being a masochist in any sense, I don’t see any advantage in being maudlin.”

His callous outlook even extended to his father’s death.

A eulogy he wrote for his father read in part:

Dear dad,

You were not a perfect man but neither am I so, if beyond the veil of death you exist and have the ability to hear me, I say that I forgive you your frailties and I ask you to please forgive mine.

Death is inevitable and wallowing in sadness over your passing is something I consider an unproductive indulgence of weakness ... Rather than be devastated by your death, I consider it a better thing to be glad that the burden of your long human existence is now behind you.

Your death means to me the loss of someone important who’s always been there but casting aside self pity, I hope it means for you the beginning of something that’s glorious.

Haigh’s eulogy — along with other references to his “spiritual masters” — suggested he may believe in life after death; possible redemption on the other side.

Or that he fears a one-way trip to hell.

His ramblings were littered with references to flames.

He made mention of “hot coals” being his “nightly bed”.

In one passage he likened jail life to being doused in petrol, set alight and then condemned to suffer “the inevitable scars the long conflagration leaves”.

“Continuing with the fire metaphor,” he read out in court, “if a man has been set alight by the authorities and he screams in pain as his life melts away then I contend it’s unrealistic to expect the victim of flame to obey any demand or official order that tells him he isn’t to try putting out the fire in any way he can.”

Such an obsession with fire might have suggested a narcissistic complex, or a fearful vision of what awaits him on the other side after death.

IN July 1979, Haigh, then aged 21, committed arguably the worst of his seven murders.

Sitting in a car in Ripponlea with a woman named Sheryle Gardner, he shot her at close range in front of her son, Danny Mitchell, aged 10.

Haigh shot Ms Gardner, 31, because she knew too much about crimes he’d previously committed.

According to Haigh, he feared Ms Gardner would “tell a story to the police” so he shot her “to shut her loosened troublemaking mouth”.

Haigh then consoled young Danny, before turning another gun on the boy.

This is how Haigh justified murdering the child: “Danny being present complicated matters greatly ... Poor young Danny seen me shoot his mother.

“I said, ‘It’s going to be all right Danny’, or words near to this and then with his back towards me I shot him three times in the back of the head with the second gun that I had.”

In a book of letters Haigh wrote called The House of Blue Light, he stated of the mother/son murder: “Because the first gun jammed as a result of what I assume to be too rapid fire, I took the second gun from the bag and used that to finish the job (of killing Ms Gardner).

“Then, while consoling the boy, I shot him with the second gun when his back was turned to me.

“I shot him three times in the back of the head and after this I turned the gun on his mother again, just to make sure she was dead.”

Haigh blamed Ms Gardner for the boy’s death, stating she shouldn’t have used him as “a shield”.

“Criminals aren’t supposed to kill children but she (Gardner) put him in a terrible situation.”

In August 1979, Haigh allowed an accomplice to rape his then girlfriend, Lisa Brearley, 19.

Haigh figured the DNA his accomplice left behind would prevent that accomplice from ever blabbing about the killing.

According to Haigh, Ms Brearley was “devalued as a person and a female” in the lead up to her savage murder.

Haigh wrote of her death in black ink.

“I invited my girlfriend to a non-existent party, and she, accepting the invitation, went to the bush with my two co-offenders and I. However, the only thing that awaited her up the dark forest track was rape and Death.

“When we arrived at the bush track one of my co-offenders asked if I was going to let others use my girlfriend for sex. He asked me this shortly after I had produced a knife and put it to her neck so she was, by the appearance of the blade, clearly aware that things had suddenly become unfriendly.

“I hadn’t known her for long but I experienced her as a kind-hearted and nice-enough lass. Unfortunately for her, because there wasn’t a gun to shoot her with, a knife was used to take her life.

“When the fellow who wanted sex with her had finished using her body to that end, I attacked her with the blade. Amazingly, it seems I stabbed her 157 times.

“I hadn’t stabbed anyone to death before ... She fought surprisingly hard, and this fazed me. Because of this, when she was finally still, I decided to stab her more in order to make sure she was dead.”

In another version he said of the fatal stabbing: “I only intended to do 20 but I lost count. So I then started counting again.”

Haigh said Ms Brearley was killed simply because she had knowledge about the weapons used to kill Ms Gardner and her son.

“So this made Lisa’s loose tongue very dangerous to us indeed,” Haigh wrote matter-of-factly.

“Lisa became a loose end we agreed to silence.”

In separate hold-ups the previous year, Haigh had shot dead Tattslotto agency worker Evelyn Abrahams, 58, and Caulfield pizza shop owner Bruno Cingolani, 45.

Haigh shot Ms Abrahams for what he called her “disobedience’’ by walking towards a door in panic rather than complying with his demands for cash.

“When this happened some strange psychological state overtook me,” he wrote in a 1986 confessional document for homicide detectives.

“It was as if everything started to slow down and go in slow motion. Colour and vision changed. Things became grey ... I recall thinking on the edge of this state, ‘No, you’re not sending me back to jail.’ I was then aware of the gun discharging and my ears ringing.

“I was not sure that I had shot the woman until I later heard on the news that this was in fact the case. That she had been shot in the head, and was dead. I then recall getting my hair cut and shaving in order to change my identity.”

He said he shot Mr Cingolani because he, like Evelyn Abrahams, did not hand over money.

Of Mr Cingolani, Haigh said: “His actions resulted in his dependants losing him.

“They (armed robbery victims) should have sufficient control of themselves for the span of the offence to enable the crime to go its ugly way.”

In his The House of Blue Light book of letters he wrote: “Though I was a lone gunman in both cases, firearms have triggers that don’t take long to pull. The woman was shot once in the head, and the man was shot once in the abdomen.”

In court, Crown prosecutor Peter Rose, SC said: “He talks about a significantly dangerous amount of power and then seeks to blame the victims.”

HAIGH shot dead an associate, Wayne Smith, in a St Kilda Rd flat in 1979 so he “wouldn’t look weak’’ in front of accomplices.

“The day after he was murdered I went to give my false condolences to his loved ones,” Haigh wrote in one of his letters.

“After the funeral service we went to the cemetery and saw the deceased lowered into the ground ... I told the deceased’s girlfriend I didn’t think (an associate) was the perpetrator, even though I’d watched him shoot the deceased man a few times with a .22 rifle, after I’d shot the victim once with a .25 pistol.”

Haigh also wrote: “I didn’t tell the victim’s girlfriend that she was lucky to be alive, as on the night that he met his end I had her targeted for demise. I had her in my sights for badmouthing me and when she wasn’t home I helped to kill her boyfriend.”

In prison in November 1991, Haigh killed fellow prisoner Donald Hatherley, who was hanged in his cell.

Hatherley was a long-suffering depressed prisoner with “no horizon of hope”.

While Haigh originally contended he was simply helping Hatherley in his quest, a court heard that, before Hatherley’s death, Haigh was upset that one-off gunman Julian Knight had slain one more person than he had.

After deciding on hanging as the method of death, according to a Supreme Court judge, Haigh “affixed the noose around Hatherley’s neck and, at his request, tied his hands with a piece of material”.

The sentencing judge continued: “After ascertaining his resolve to continue his path to self-destruction, you pulled away the small cupboard upon which he was standing, leaving him suspended.

“But Donald Hatherley did not die immediately. He continued to take shallow breaths. On your account, you rubbed his chest while saying: ‘Let go of your breath, my friend.’”

Hatherley continued to struggle for air for another two long minutes before Haigh pushed him down by his shoulders to finish the job.

The sentencing judge said it was later revealed Haigh’s motivation “extended beyond any altruistic concern” for Hatherley.

“Indeed,” the judge said, “you told the police you were glad that Hatherley wanted to commit suicide because of the benefit you could get out of it. That benefit was the opportunity to expose yourself to a ‘new plane of experience’, as you perceived it, by assisting someone to die without any malice.

“You also described your participation in Hatherley’s death as ‘an adventure’ ...(and) as a challenge and as a vehicle for personal growth.”

In the Supreme Court in 2012 during Haigh’s minimum-term application, Crown Prosecutor Peter Rose asked Haigh if his murder accounts were still accurate.

“The facts are the facts,” Haigh replied coldly.

Mr Rose cross examined on a range of other topics.

Incest, Haigh said, was “a matter for consenting adults”.

“I reason that by way of the Bible,” he explained.

“If Adam and Eve are the first two people on the planet then we’re naturally the product of incest.”

Illicit drug use was okay, too.

“That’s the way I cope (in prison),” Haigh told Justice Beach.

He also said he’d sought to learn and avoid fiery damnation.

“I used to read book after book, looking for answers to the mystery of life,” Haigh said in court.

“I was after what God would base judgment, reward and punishment on — not the relative ideas of mortal man. I’d lived, read and thought enough to see that what we call creation is a miraculous thing and if the amazing universe we see can exist, I couldn’t rule out the possibility of having a soul that could be judged.

“So I wanted to know the truth about good and evil in order to be able to do what would spare me the possibility of an afterlife in hell.”

During the Supreme Court application, consultant psychiatrist Dr Yvonne Skinner told Haigh, while being cross examined by him: “At the time of the killings I think you would have been described as having a personality disorder because it affected your functioning to the extent that you got into so much trouble, and it would have been defined as anti-social personality characteristics ... You have some obsessional characteristics as well.”

Haigh: “What would you say my self image is? Do I have self-image problems?”

Dr Skinner: “Probably, yes.”

Haigh: “Do I have emotional problems?”

Dr Skinner: “You don’t have a diagnosis, and I don’t think you had a diagnosis at that time of a mental illness, a psychotic illness or any other severe mental illness or psychiatric disorder.”

In refusing Haigh’s application for a minimum term, Justice Beach said Haigh’s first six murders — the subject of the application — were “callous, brutal, disgraceful and entirely unjustified”.

“I have real doubts as to whether the applicant has truly experienced any real remorse in respect of any of his crimes,” Justice Beach said.

Haigh was duly returned to jail, where he faces a possible fiery damnation upon his death in custody.

LADIES UNDERWEAR: The case of the twisted killer colonel

INSIDE STORY: How a thief helped nab Oklahoma’s evil bomber

MELBOURNE’S MOST SHOCKING CRIMES: CBD | North | East | South | Peninsula

DEATH ON THE MENU: Gatto dodged a bullet, others didn’t

UNDERWORLD CONNECTION: Carl Williams and the Esky in the boot murder

THE BIKINI KILLER: Charming playboy left a trail of death

GIANT READ: How a Google search foiled tomato tin mafia’s multi-billion drug plot