Bikie war between the Bandidos and Comcheros left seven dead at the Milperra Father’s Day Massacre

FATHER’S day celebrates mens’ best, but on an awful day outside a pub, the Bandidos and the Comancheros unleashed their worst in a hail of bullets that left a 14yo girl dead.

True Crime Scene

Don't miss out on the headlines from True Crime Scene. Followed categories will be added to My News.

It was 30 years ago today that the Bandidos and Camancheros went to war outside a Sydney tavern. Everyone involved was scarred for life.

“They had declared war on each other; it was a display of power to win respect.”

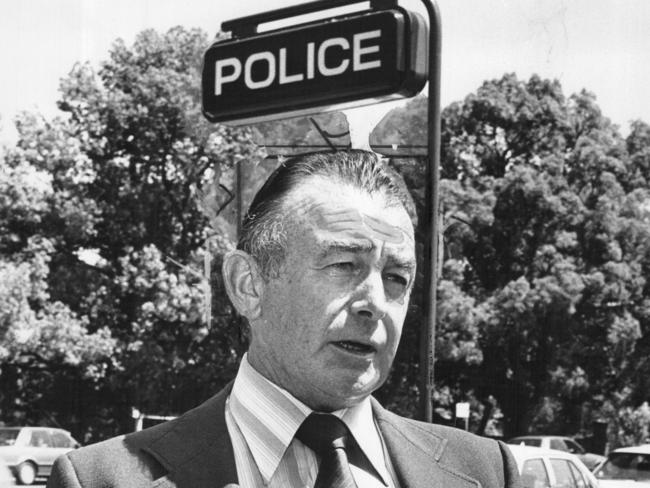

That’s how former New South Wales police officer Ron Stephenson described the reason for the infamous Milperra Massacre — a brutal and deadly clash between the feuding Bandidos and Comancheros bikie gangs at a pub car park 30 years ago today.

Known as the “Father’s Day Massacre”, it was a clash between two wild tribes at a motorbike swap meet outside the Viking Tavern in Sydney’s south west.

It would end as one of Australia’s most infamous gunbattles — a full-scale rebel war on a sleepy Sunday afternoon in a hotel car park packed with more than 500 people.

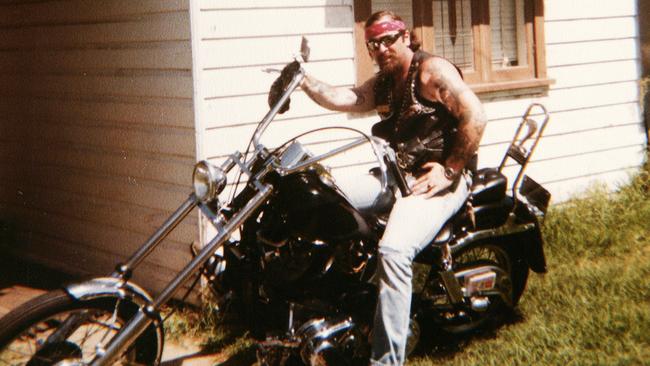

The battle’s genesis dated back to a time when a branch of the Bandidos, regarded by the FBI in the US as one of the “Big Four” outlaw bikie gangs, was formed in Sydney in 1983.

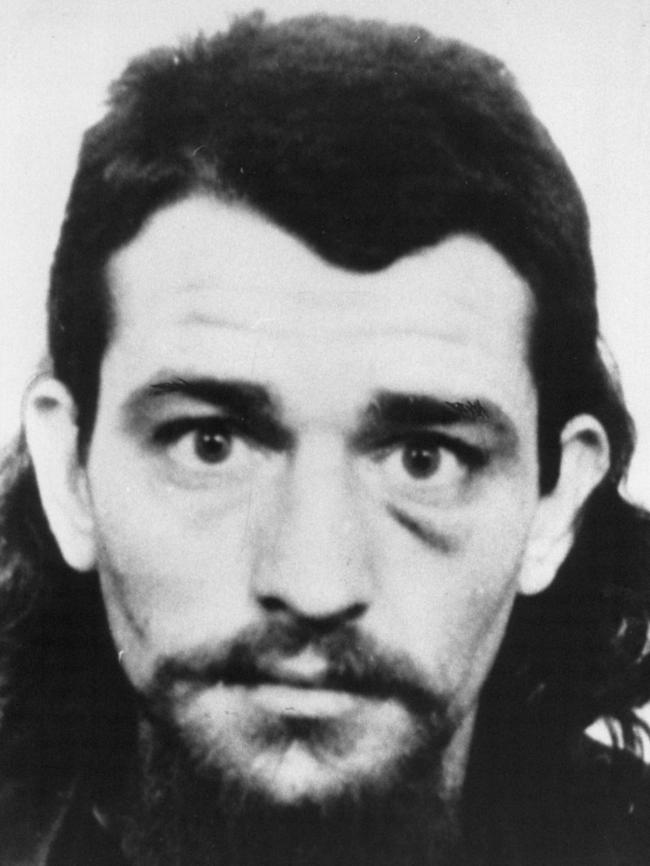

Arthur “Snoddy’’ Spencer and Charles “Charlie’’ Scribberas, both members of the Comancheros, deserted the club and burned their colours — an unforgivable act.

The US headquarters of the Bandidos saw its fledgling chapter in Sydney as an outlet for drug distribution, with the main wealth of outlaw bikie gangs coming from the manufacture of amphetamines.

War was formally declared between the NSW Bandido and Comanchero gangs on August 8, 1994, a few weeks before the Milperra confrontation.

It was simply a matter of time before the rival gangs clashed.

It happened at the bike swap meet, organised by the British Motorcycle Club, in the Viking Tavern’s car park, attended by most of Sydney’s motorcycle fraternity.

On sale were car and bike parts — new, second-hand and hot.

The Comancheros arrived about 1pm, all heavily armed.

Shortly after, thirty Bandidos rumbled into the car park, rifles and shotguns in scabbards fixed across their handlebars.

A back-up van followed, carrying more weapons.

There was an air of tension as each side lined up at opposite ends of the car park.

And then it was on.

Shotguns and automatic weapons blazed during the conflict.

Blokes used baseball bats, machetes, chains, iron bars, knives and knuckledusters at close range.

Bystanders ran screaming from the scene, while others hid behind trees and parked cars and ran into the hotel.

The shocking battle left six bikies — four Comancheros and two Bandidos — and an innocent 14-year-old girl dead.

The girl, Leanne Walters, was an innocent bystander killed by a rifle shot.

Four of the dead bikies died from shotgun blasts and two from .357 magnum rifles.

They were: Bandidos Greg “Shadow” Campbell and Mario “Chopper” Ciantar, and Comancheros Phillip “Leroy” Jeschke, Ivan “Sparrow” Romcek, Robert “Foggy” Lane and Tony “Dog” McCoy.

A total 21 people were horribly injured.

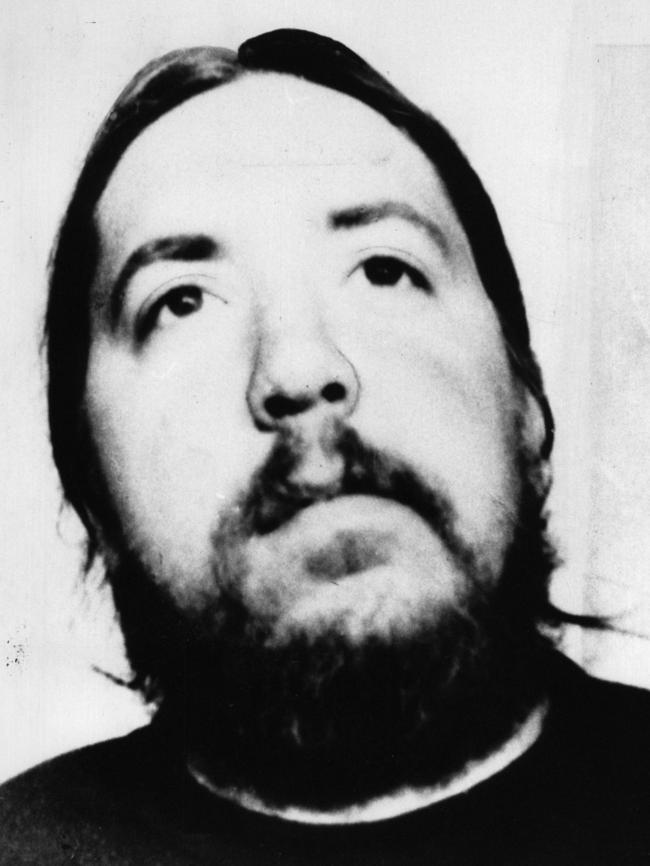

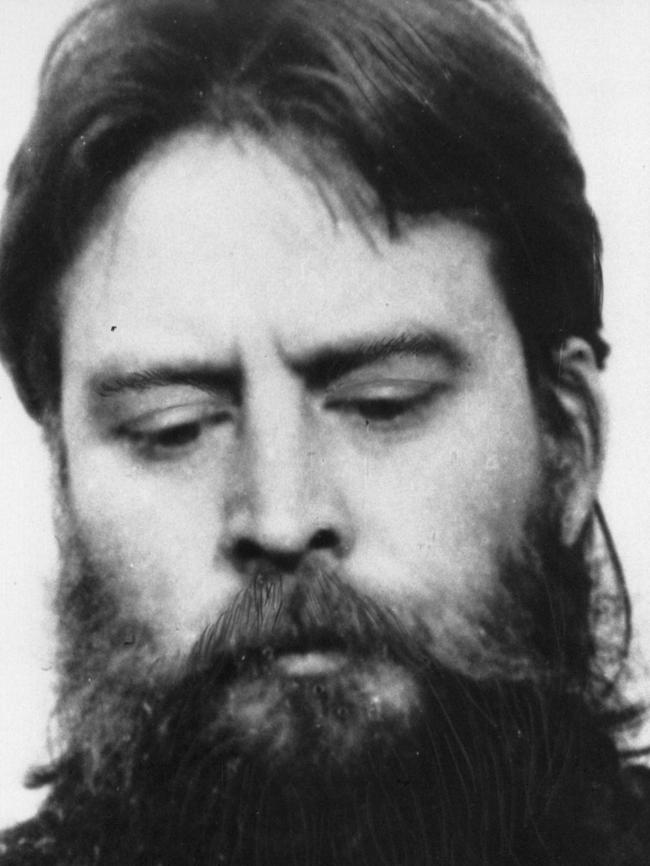

Comanchero leader Jack Ross was hit twice by shotgun blasts, but survived.

The first shot hit him in the head, knocking out teeth and penetrating his brain.

The second blast tagged him in the chest.

Another Comanchero member, Kevork Tomasian, a concert pianist, was blasted in the left arm.

The Campbell family, which had several brothers at the tavern that day, suffered worst.

Greg Campbell was among the dead, and other brothers were wounded.

John “Whack” Campbell would die three years later from cardiomyopathy quite possibly caused by complications from his original wounds.

Geoff “Snake” Campbell would years later lament the loss of his Bandido “brothers”, while calling the Milperra confrontation a “mistake”.

“It’s like having your heart torn out,” he would tell The Daily Telegraph in April 2009.

“A part of your life is gone and you’re never going to see them again until you’re in heaven. It’s a gut-wrenching feeling — you think your family is going to live forever.”

Ron Stephenson (who died in a car crash in June 2005) spent three years investigating and prosecuting the case.

“In the middle of it all,” Mr Stephenson told TheDaily Telegraph Mirror in August 1994, “the pub staff were still selling beer. People actually sat in the hotel drinking while the war was going on outside.

“I will never forget the sight when I arrived that day. The car park was packed with leather-clad bikies, police and ambulance officers treating the injured.

“One sergeant arrived with a young constable and commented, ‘Take a look at this son because you’ll never see anything like it again.’

“The bikies appeared to be quite proud of what they had done.”

John Garvey, then a senior constable, and his partner, Det-Sgt Trevor Baker, were among the first officers to arrive at the pub carpark.

“We had a couple of bulletproof vests and shotguns in the car but nothing to prepare us for what we saw,” Supt Garvey said in August 1994.

“There were people everywhere and shots were still being fired when we pulled up behind the hotel.”

The first person Mr Garvey saw as he came out of the hotel was Raymond “Sunshine” Kucler, a wounded Comanchero with a smoking shotgun in his hands.

“Kucler was covered in blood and appeared to have a wound below one eye,” Mr Garvey recalled.

“He was very pent-up; you could see the anger and emotion in his eyes. The situation had suddenly changed, and I knew it was a critical moment in which my life was in danger. Here I was armed with a shotgun facing a very angry man with a shotgun he had obviously used; it was not something I could walk away from.

“Kucler wanted me to get ambulances to help his injured mates but I told him we couldn’t until he surrendered his weapon. We argued and finally he said he would give up his gun if I did the same.”

Both men laid down their arms.

“The wounds on the men were horrific,” Mr Garvey said of the carpark battlefield.

“I mean, those sorts of weapons can do some terrible damage.”

A spokesman for the Viking Tavern told The Daily Telegraph Mirror that the day of the massacre was the first Sunday the hotel had ever opened for business.

“The tavern never traded on a Sunday because it is in an industrial area,” the spokesman said.

“The licensee agreed to allow a swap meet in the car park to attract customers. Everything was going fine until these two gangs turned up out of the blue and started shooting each other.”

Despite the death and carnage, the many men jailed for their part in the chaotic clash were released from prison well before the massacre’s ten-year anniversary came around.

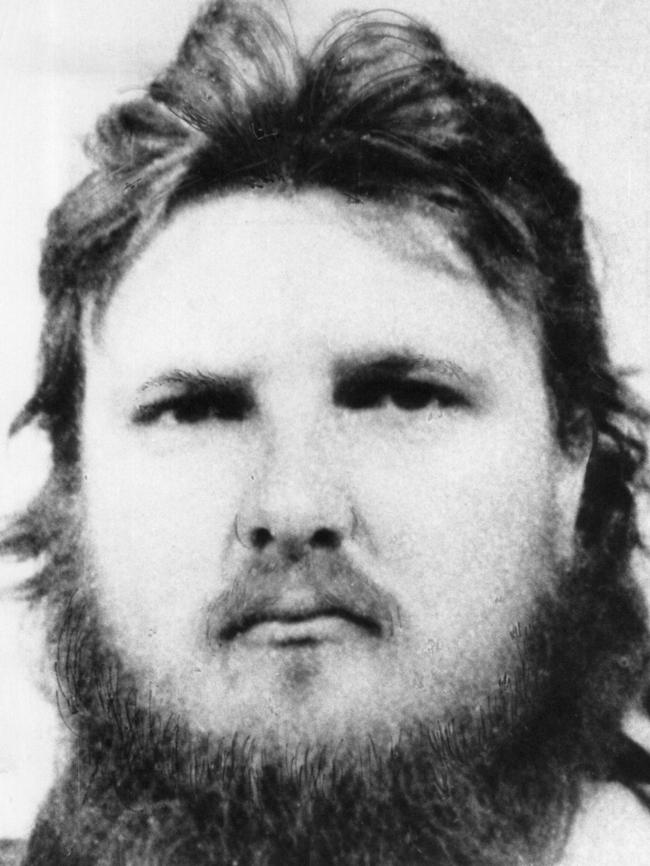

Nine men — Jock Ross, Gary Annakin, Glen Eaves, Robert Heeney, John Hennessey, Raymond Kucler, Tony Melville, Ian White and Terrence Parker — were originally convicted of murder and sentenced to terms ranging from 18 years to life imprisonment.

All subsequently won appeals to the Court of Criminal Appeal and had their murder convictions quashed and reduced to manslaughter.

In August 1989, the High Court refused an application by Crown prosecutors for special leave to appeal against the decision, saying the court would only restore murder convictions in exceptional circumstances.

The bikies’ girlfriends and partners supported them throughout the court process.

A total 21 men received sentences of 12 years with a seven-year minimum.

Another five received sentences of ten years with a six-year non-parole period, three received 14-year sentences with eight-year non-parole periods.

Ross was handed a 15-year term with a nine-year minimum.

Many were also convicted of affray.

Ross served the longest sentence — five years and three months — which equated to a third of his total sentence.

Due to a series of remissions allowed under the complex parole system of the day, he was released on December 7, 1989.

According to Corrective Services Department records, none of the members of the two gangs jailed for manslaughter served their minimum terms, let alone their maximum sentences.

Due to the laws at the time, all but one man received an automatic one-third remission because it was their first conviction involving a jail sentence.

Other remissions included a working or industrial remission and an education remission for taking part in courses while in prison, as well as remissions for good behaviour.

Bandido Raymond Denholm was the first bikie released, on March 11, 1988.

He served less than 3 ½ years of his ten-year sentence, despite a non-parole term of six years.

The last bikie let free was Bandido Colin Campbell, who was arrested much later and served four years and two months.

By ten years on, most involved had gone their separate ways.

On the tenth anniversary, The Daily Telegraph Mirrortracked down some of those involved.

Most, if not all, of the bikies involved had turned their back on the motorcycle gang culture.

Jock Ross said he was angry at being considered responsible for the bloody incident.

“I can look at myself in the mirror and know that I was not to blame ... I did not cause what happened,” he said in August 1994.

“Of course I regret what happened. I lost four good men and we got totally screwed. I was the one who ended up being shot up, so how could I have killed anyone?

“They judged me for who I am, not what I did.”

Another former bikie, who wished to remain anonymous, told the newspaper: “Milperra was catastrophic; it was a ridiculous and terrible thing to happen.

“We have all paid a terrible price and we will never be allowed to forget it or escape from it ... Milperra changed everything.

“We came from all walks from life — optometrists, engineers, clerks and blue collar workers — and all had our reasons for being there (in a motorcycle gang).

“Many of us just wanted to escape our dreary lives; escape for one night a week, dress up like Marlon Brando and be a wild one.”

Former CIB superintendent Ross Stephenson, who had retired from the police force by 1994, dismissed arguments by the gangs that there was no intention to start an all-out war at the tavern.

“I simply can’t accept that,” Mr Stephenson told The Daily Telegraph Mirror.

“They knew it was going to happen and both gangs were prepared for the fight. They had declared war on each other, and once that happens you can be assured a full-scale battle will take place if they meet in public.”

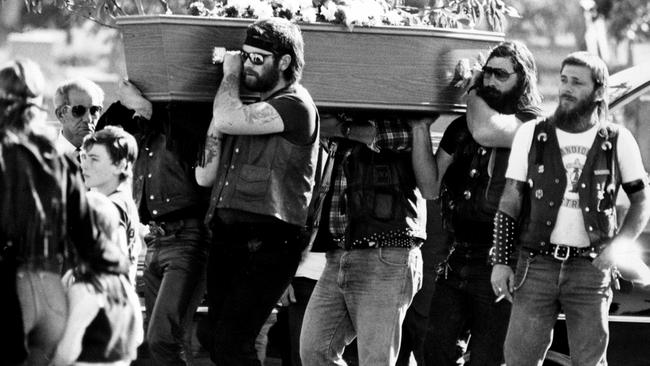

Some of the former bikies have since died.

Some of their funerals were held in secret for fear of reprisal attacks.

“JJ” Heeney, who died in a motorcycle accident in February 2008 at age 50, was buried after his body was escorted through Sydney suburbs by a funeral procession of up to 200 bikies.

A police officer named Mark Pennington, one of the first on the scene, was awarded $380,000 for psychological damage because he received no counselling following traumatic events throughout his career.

He described the scene as horrific.

“I was terrified that day might be the last day. I was very fearful for my own safety.”

In 2012, Channel 10 aired a six-part miniseries entitled Bikie Wars: Brothers In Arms about the build up to the massacre, the incident itself and the characters involved.

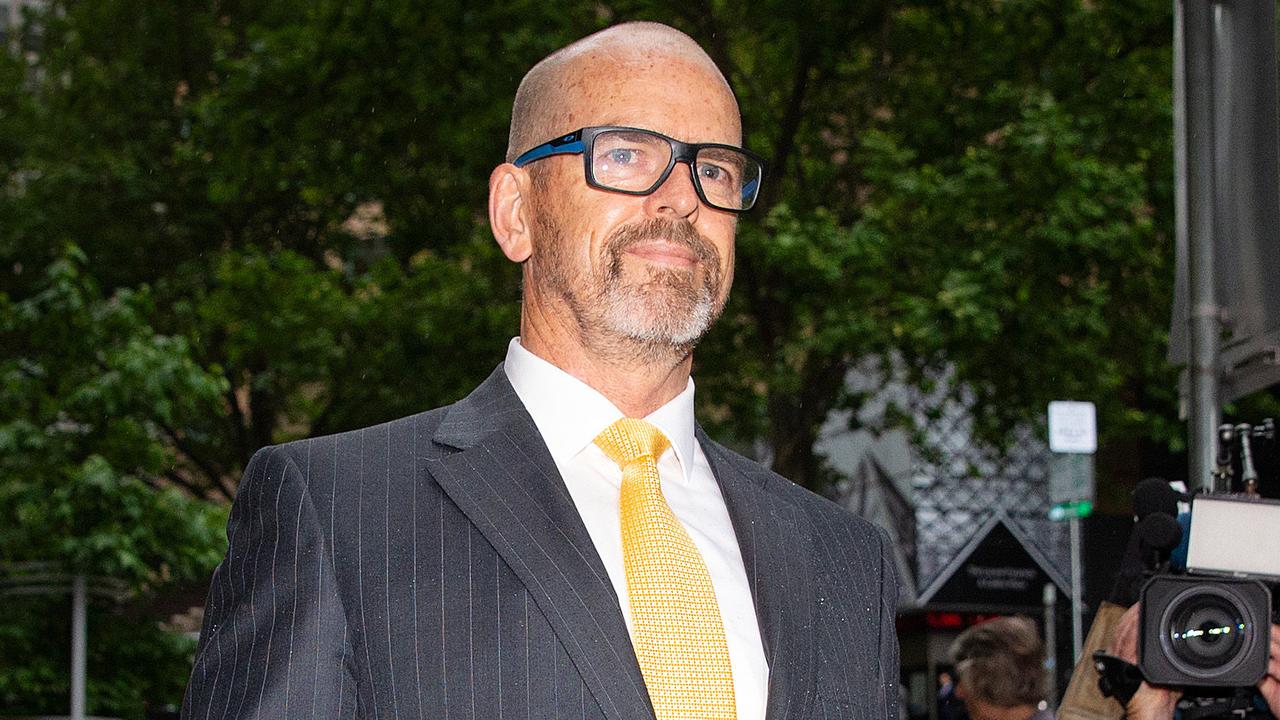

It starred Matt Nable as Jock Ross and Callan Mulvey as “Snoddy” Spencer.

Doing justice to the story was a challenge for Mulvey.

“They’re very protective of the brotherhood and they bloody should be,” he told the Herald Sun in May 2012.

“They would die for each other and I have the upmost respect for the clubs. You’ve got your brother’s back and nothing will come between that.

“You take your brother’s side first and I think that would be a beautiful thing to experience.”

That’s not to say the criminality is to be admired or excused, Mulvey said, but honouring the story and the relationships was a key to getting the story right.

“It’s hard to get it right for both sides ... both sides seem to have conflicting stories and there will be a lot of people who feel Snoddy shouldn’t be made a hero or that Jock’s been demonised,” he said.

One man worried about the series before it went to air was Rex Walters.

He told The Sunday Telegraph he was concerned about how his daughter — who was at the bike swap meet with a friend of his — would be portrayed.

Mr Walters said Leanne’s reason for being at the Viking Tavern that fateful day “wasn’t because she was involved with a bikie”.

“There have been bad things written about her in the past which aren’t true,” Mr Walters said in April 2012.

“I just want my daughter to be remembered properly.”