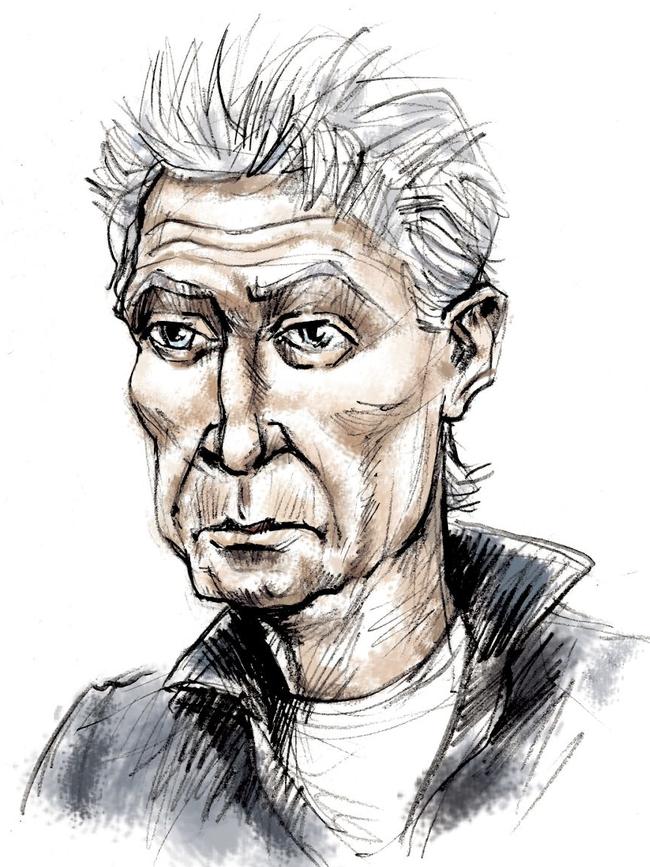

Suspected of at least nine murders, Rodney Charles Collins was a killer hiding in plain sight

SOME knew him as The Fox, The Duke, even Uncle. But all knew Rod Collins for what he was: a killer. Is it really possible he got away with seven murders?

Law & Order

Don't miss out on the headlines from Law & Order. Followed categories will be added to My News.

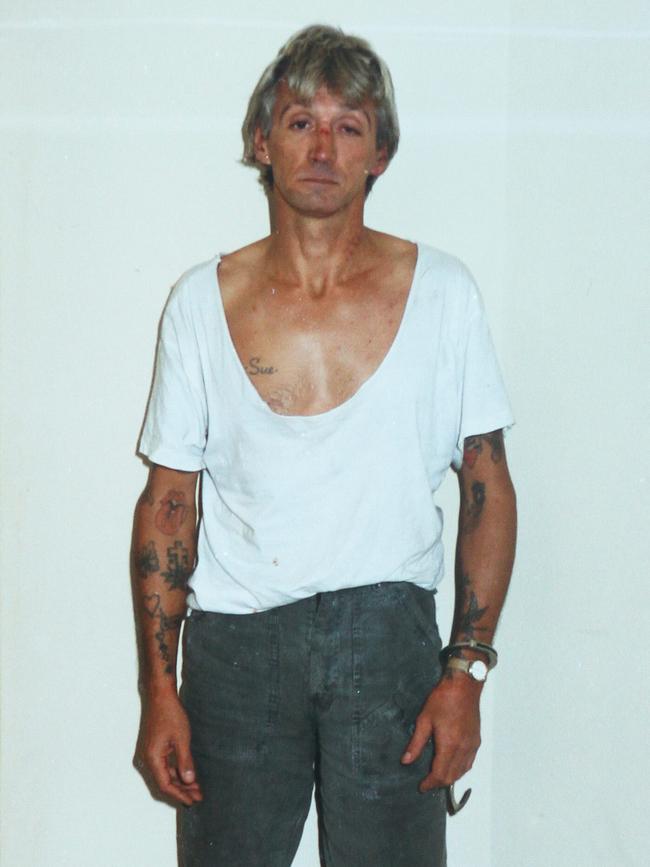

AS a young man he lacked an imposing build.

But Rodney Charles Collins quickly learned that with a gun in your hand you’re bigger than just about anyone.

To some he was Cherokee, or Rod Earle. Others knew him as The Fox, The Duke, or even Uncle.

MONSTER DIES IN JAIL TAKING SECRETS TO GRAVE

CARL’S GO TO KILLER BUTCHERED WITHOUT MERCY

But all knew him for what he was: a killer.

Some might say it’s hardly fair that natural causes got him in the end.

Not only for the injustice of it — he had many, many more years to serve in a cell — but because the answers he almost certainly held to some of the state’s most brutal executions now go with him. Seven murders that now seem less likely than ever to be solved.

Raised by loving grandparents until the age of eight, his own account was of a happy childhood until the day Collins was returned to his alcoholic parents.

From then on, the only constant was violence.

That was until the day Collins, aged 14, stood up to his brute of a father and walked out.

The man’s parting blow was to reveal he was not Collins’s father.

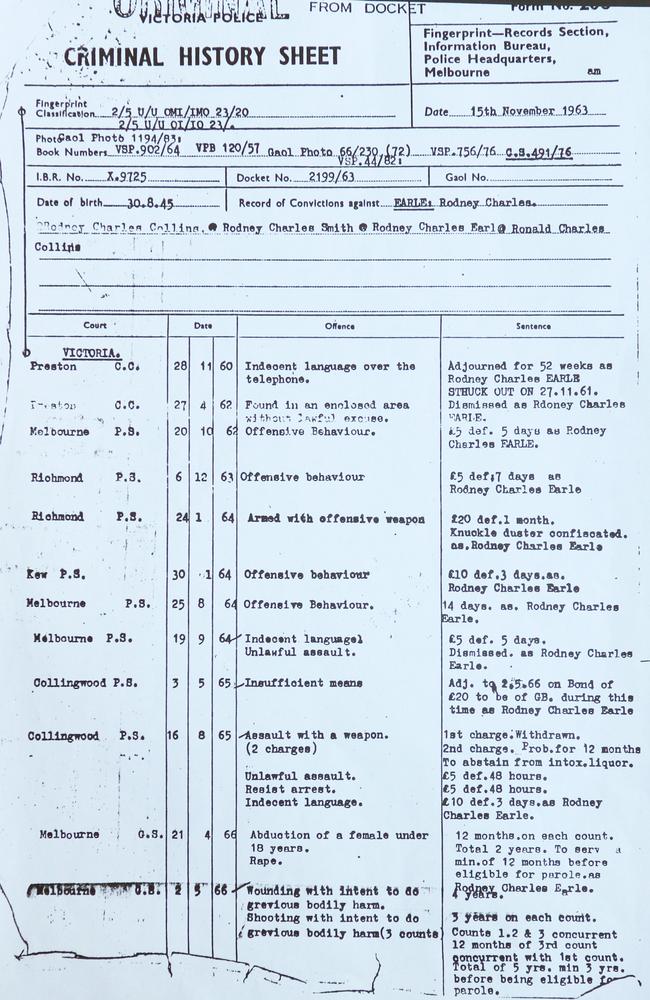

Alone on the streets of Richmond in the 1960s, Collins fell in with local gangs and earned his first conviction as a teenager.

By 22, he was doing five years for a shooting.

He would go on to earn convictions for other serious offences, including rapes, before finally progressing to murder.

He was a hard man, and a hard man to forget.

A woman who knew Collins in the mid-1980s recalled decades later:

“Earle was about five foot seven, grotty-looking, unkempt.

“Had wiry build with drawn features. He was scowly and always had a mean look on his face.

I thought he always had a mean-spirited vibe about him.”

The shooting of Patrick Brendan Coughlan

On February 5, 1983 Collins shot one man dead and injured another.

The shooting, at a party in Reservoir, was witnessed by several guests but the survivor, host Ronald Longmuir, claimed at first that he did not know his attacker.

Six months later he told police a different story.

The party had been going for many hours.

Collins and his girlfriend lived across the road, but by the time they arrived many of the guests had gone.

But the beer was still flowing and Longmuir would later say, “I’d had me share. I wouldn’t say I was blind.”

He told police he was sitting in his rocking chair while Collins, whom he knew only as Rodney, was standing near the fireplace.

Longmuir’s friend Patrick Brendan Coughlan, known as Brendan, arrived with half a dozen stubbies.

They chatted about fishing and Coughlan offered to replace a fishing rod he’d lost.

“The next thing I remember was seeing Rodney put his right hand into his trouser pocket,” Longmuir told police.

“He then pulled something from his pocket which was small and black.

“I then felt a thud in the thigh of my left leg like I had been hit with a sledge hammer.”

He described hearing his friend’s cries as he fell to the floor.

“I then remember Brendan saying to me, ”Ronny, Ronny, the bastard has shot me in the guts.”

He could not say why he had been shot, but Longmuir had broken up a fight three years earlier in which Collins had been a participant.

Collins was known to have a short fuse, and a long memory.

The day after Longmuir came clean to police they arrested Collins.

He was already their top suspect anyway.

As was the protocol, an inquest was held at the Coroners’ Court.

But Longmuir was far less cooperative than he’d been with police earlier.

He was argumentative, gave conflicting answers, and claimed he had not told police about being offered money to keep quiet.

It did his credit no favours, but helped Collins enormously.

A jury never got the chance to hear his version of events.

Longmuir died before Collins faced trial in 1985.

His statements and evidence could have been admitted, but were deemed too unreliable by the trial judge.

The same judge also ruled out other identifications of Collins as the killer by eyewitnesses, including Longmuir’s young son and wife.

Collins spent two years in Pentridge before being released, and by 1987 two more people were dead.

The killings of Ray and Dorothy Abbey

MARK McConville had stuffed up big time.

Taking a Rolex watch from the scene of an horrific double murder was not smart.

And wearing it was bordering on a death wish.

It was the only real evidence linking him to the killings of Ray and Dorothy Abbey — and Collins could not afford to have police connecting McConville to him.

Collins and McConville had killed the couple at their West Heidelberg home, shooting Abbey and slitting his wife’s throat.

Their young kids had been shut in their bedrooms.

Collins and McConville had used stolen police uniforms and a fake warrant to gain access to the house.

They left disappointed when they had to kill Abbey before they’d gotten the drug dealer to open his safe.

Police caught up with McConville, but the 25-year-old refused to give up the man he knew as “Uncle”.

McConville stood trial and was found guilty, but still did not dob in Collins.

He was released after a retrial cleared him of the killings.

Collins never missed a chance to berate him about the watch — or remind him of the consequences of lagging on him.

McConville’s girlfriend recalled meeting Collins in the early 1990s.

“He had a gun tucked into the front of his jeans which he made very obvious by pulling his jacket across,” she said.

“He leant right into my face and said do you understand that you have not met me?

“You don’t know me and I was never here.

“He said if the police ever associate us (himself and McConville) together, I am gone.”

To McConville, he raged:

“If you ever give me up for the Abbey blue and I get done for it, I know how I would get you.”

The girlfriend remembered Collins saying he would kill McConville’s mother as “that was the only way to get at him because he didn’t have kids or a wife or stuff”.

McConville kept his mouth shut.

It wasn’t until more than 15 years later that Collins was charged with the murders.

A man and his gun

Collins was never far from a gun, and over the years was regularly caught with them by police.

When police came for him in 2008, they found a hitman’s tools of trade — surveillance gear and a loaded-gun. They also found a confidential police report on another criminal.

Two decades earlier police had raided a house in Footscray looking for him, and found a loaded Uberti Gardone revolver under his pillow.

But there was little deterrent in the sanctions courts were handing Collins for firearms offences.

Despite having convictions for shooting people and possessing guns illegally, he was fined in 1985 when he faced court for possessing a pistol without a licence.

“He is a very hardened criminal and associates with all the better known criminals in Australia,” states a secret police report on Collins seen by the Herald Sun.

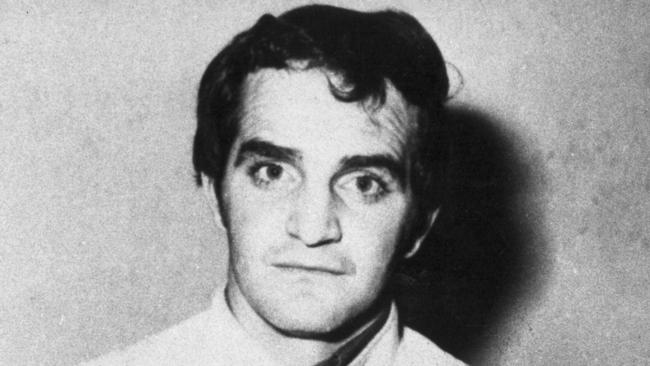

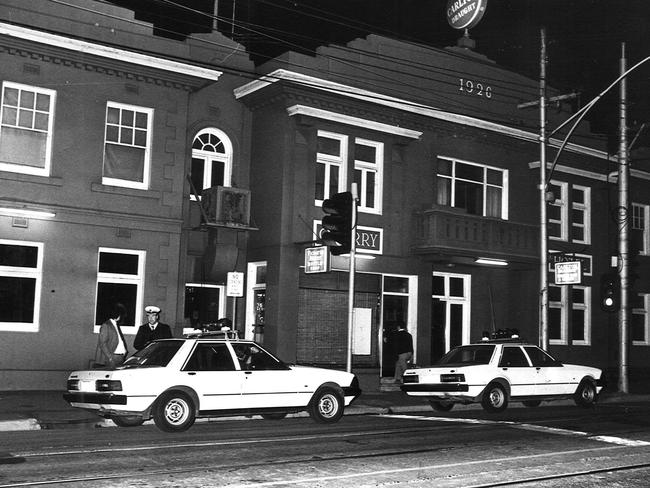

The murder of Brian Kane

Underworld figure Brian Kane’s 1982 murder remains unsolved, and talk of it usually draws forth whispers of Collins’s name.

Kane had arrived at the Quarry Hotel in Brunswick on the night of November 26, 1982, around 9pm.

It was rumoured he had given his female companion his gun, which was in her bag when two gunmen wearing balaclavas had walked in and shot him in the head and chest.

Dennis William “Greedy” Smith was quizzed by police over Kane’s death but denied it. He wasn’t exactly devastated either.

“I thought, ‘There goes another one (of my enemies)’,” he told the Herald Sun in 2010.

He srecalled a mate giving him the news: “Greedy, pop the champagne corks, Brian Kane has got his head blown off’.’’

But another suspect — Collins — largely slipped under the radar.

There is a $100,000 reward on offer in that case.

But to some, even that amount of cold hard cash isn’t enough compensation for getting on a killer’s wrong side.

Two double killings, same method

Drug dealer Michael Schievella and his de facto wife, Heather McDonald most likely knew their killers.

Their hands were bound and their throats cut at their St Andrews house in 1990.

Their children, aged eight and nine, were at home and the killers tied them up in their rooms. They were left to discover their parents’ bodies.

The crime happened on a Sunday, between 8am and 10.30am.

It’s hard not to note the similarities to another double murder, one that police are still determined to solve: that of Terry and Christine Hodson.

In 2004, just months before the Hodsons were bound and shot dead in their Kew home, Rodney Collins was given a community-based order for being a prohibited person in possession of a firearm.

He had a loaded semiautomatic pistol in his car as he drove through Melbourne’s eastern suburbs.

Facing charges over the murders of the Abbeys in 2008, Collins flagged his interest to talking to Det-Sgt Sol Solomon.

Solomon wasn’t working the Abbey case. His investigation was into the Hodson murders.

Making his approach to police via his partner, Collins discussed making a deal and what role the million-dollar reward on offer might play.

But no deal was made.

Collins was charged with the Hodson murders, although the case was later dropped.

A jury convicted him of the Abbey murders partly on incriminating comments Collins had made while discussing the possible Hodson deal — conversations police had covertly taped.

And behind bars, the feared mercenary has now become the target.

He became “unpopular with other prisoners”, who believe Collins is “providing information to the police about his past crimes or his possible knowledge of other crimes”, according to a statement by Brendan Money, the Director of the Sentence Management Branch of Corrections Victoria.

In 2011, CCTV footage from Barwon Prison showed Collins being manhandled by another inmate.

He later appeared with a black eye.

His explanation that he’d fallen in the shower wasn’t fooling prison authorities, who moved him into virtual isolation.

Collins did it hard after that, spending almost 23 hours a day alone.

MORE NEWS: