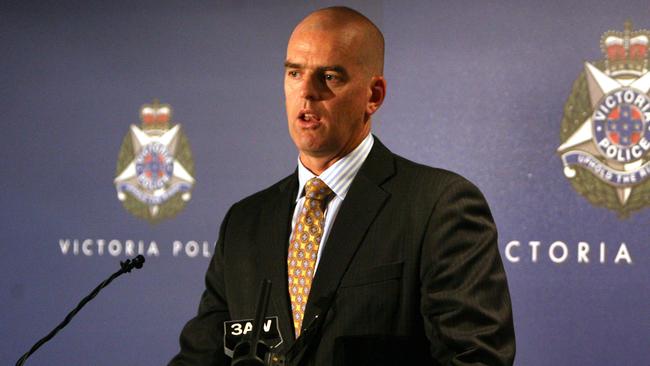

Simon Overland fronts royal commission

They never met but Simon Overland and Nicola Gobbo were connected by a shared desire to jail gangland figures. And while Overland may not know the details of Gobbo’s informing, he still has plenty to say.

Law & Order

Don't miss out on the headlines from Law & Order. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Former assistant commissioner Noel Ashby stares at the man a few feet from him. Ashby has spent many years wondering about the man, Simon Overland, who investigated him in 2007 – even tapped his phone – which led to (unsuccessful) criminal charges against Ashby.

But Overland isn’t interested in Ashby. Not now, anyway. He is looking elsewhere, a solitary figure in a hearing room buzzing with 22 lawyers.

He is about to give evidence at the royal commission in which he is the most significant figure, bar Nicola Gobbo herself. They never met, but Overland supervised a relationship built on a shared desire to jail gangland figures.

Overland has had a tough year, including accusations of historical ill-doing, and his sacking as a local council chief executive last week. He has never relished close scrutiny. But he appears relaxed in the witness box, even risking a few lighter moments and laughs. He seems to know what he wants to say.

Overland didn’t know much of the operational detail, he said, because he was too high up the police chain. He grasped broader police hopes, and supervised strategies of getting gangland criminals to “roll” against one another. He met the first one to convince him to co-operate. But Overland said he could not recall – or never knew – many of the devils in the Gobbo detail.

Within hours, Overland’s evidence was going so smoothly that one gallery member had dropped asleep. Overland was comfortable about telling his version of events, though he had a few admissions in his first hours in the witness box.

No, he couldn’t remember telling his boss, chief commissioner Christine Nixon, about the force’s use of Gobbo as informer 3838.

He didn’t keep a diary from the time, or a day book, which was standard practice for police officers throughout the world. He did jot notes on briefing papers in an ad hoc approach.

No, he didn’t seek legal advice about the use of a defence barrister as an informer, but yes, he could have.

No, he was unaware whose Gobbo client list was when she was selling out her clients. But he said was concerned from the start – for both her and the police force – that she was an informer.

Yes, he pursued an exit strategy for Gobbo’s informing within months of her registration as 3838 in 2005, because he believed there was no such thing as a “long-term” informer. They generally ended up dead or living under a new name and identity.

Yes, Gobbo’s informing against her clients should have been revealed to those clients during the disclosure processes of the court system. Overland assumed his investigators would take care of that legal requirement.

Overland said Gobbo came to police to inform because she faced a form of “death sentence”, one way or another, because of the position she had placed herself in. She was integral to the criminal enterprises of Tony Mokbel and others. Her value and knowledge meant she could “not resign” from the likes of Mokbel.

THE NINE QUESTIONS GOBBO SHOULD ANSWER

Overland could he recall hearing of another barrister, bar Gobbo, who has worked as a secret agent against her clients.

What he said in his first hours in the witness box did not dispute the prevailing idea of a toxic relationship between the barrister and her police handlers.

Perhaps the fuller extent of this “dependence” (her words) – and any improper practices that led to feeding it – will become clearer in Overland’s coming evidence.