How clever cops and science are bringing dumb crooks to justice

THE detectives dragged in hundreds of innocent suspects but missed the killer, writes Andrew Rule.

True Crime Scene

Don't miss out on the headlines from True Crime Scene. Followed categories will be added to My News.

THE detectives dragged in hundreds of innocent suspects but missed the killer.

One rogue cop tried to flog a "confession" out of the murdered girl's ex-boyfriend but the kid had the grit not to cave in.

He was lucky, because then premier Sir Henry Bolte might have hanged him instead of Ronald Ryan to win a law-and-order election.

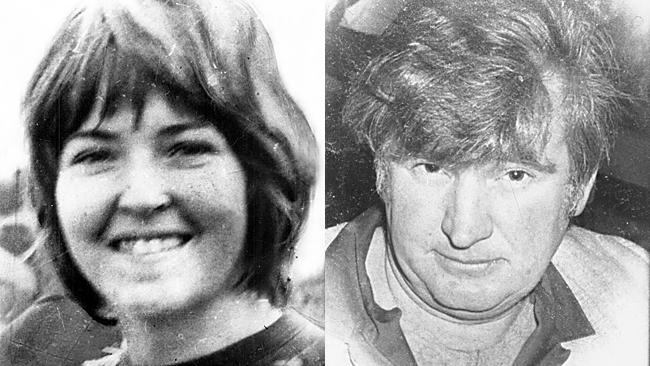

In the end, the "backroom boys" from forensics did what the old-time detectives didn't. They nailed the man who abducted and murdered Shepparton teenagers Garry Heywood and Abina Madill.

It was a win for science and common sense over hunches, punches and long lunches.

It all started the day after Garry and Abina went missing from a rock dance in February 1966, when a fingerprint expert found a small unidentified print on Heywood's FJ Holden.

The print stayed unidentified - and was kept secret - for 16 years, until a sharp-eyed fingerprint expert named Andy Wall matched it with prints left at a series of rape scenes in Melbourne's eastern suburbs in the 1970s.

The match meant police knew the suburban rapist was probably the Shepparton killer of 1966, but they did not know his name.

That changed on March 16, 1985, when a man was routinely printed in Albury after his arrest for indecent exposure.

The man dubbed "Mr Stinky" exposed himself in more ways than one that day.

He was revealed as Raymond Edmunds, who is still in jail. He will die there, if there's any justice.

Fingerprinting had finally succeeded where "old-style" conventional policing had failed.

But the case could have been solved in days or weeks - instead of decades - with a clue a ballistics expert found at the murder scene.

Brian Thompson picked up a piece of plastic trim where Abina Madill had been bludgeoned to death and Garry Heywood shot, and identified it as from a Mossberg .22 rifle.

A simple check of known Mossberg owners would have fingered Edmunds, but local police dropped the ball and let the killer run free for another 19 years, during which time he committed dozens of violent rapes.

Eventually, the Edmunds case was a triumph of good forensic work over shoddy detective work.

Not that forensic science has always been infallible.

The "foetal blood" debacle that allowed the Lindy Chamberlain miscarriage of justice proves that.

But year in, year out, crime scene analysts prove hundreds of cases beyond reasonable doubt. They are the quiet achievers of law enforcement.

It is just over 50 years since Victoria's crime scene unit started work, 25 years since it moved from the old Spring St forensic office to the purpose-built complex at Macleod.

It is almost 100 years since the force opened a fingerprint branch, about 80 since the ballistics section started.

As drug-related crime has spiralled, the chemistry division has grown, too. And with the rising importance of DNA, the biology division is growing fast - it's as revolutionary as fingerprinting was a century ago.

But these are laboratories, staffed by civilian scientists. Only sworn police staff the Crime Scene Division, which takes in fingerprints, ballistics, photographic, vehicle examination and disaster victim identification.

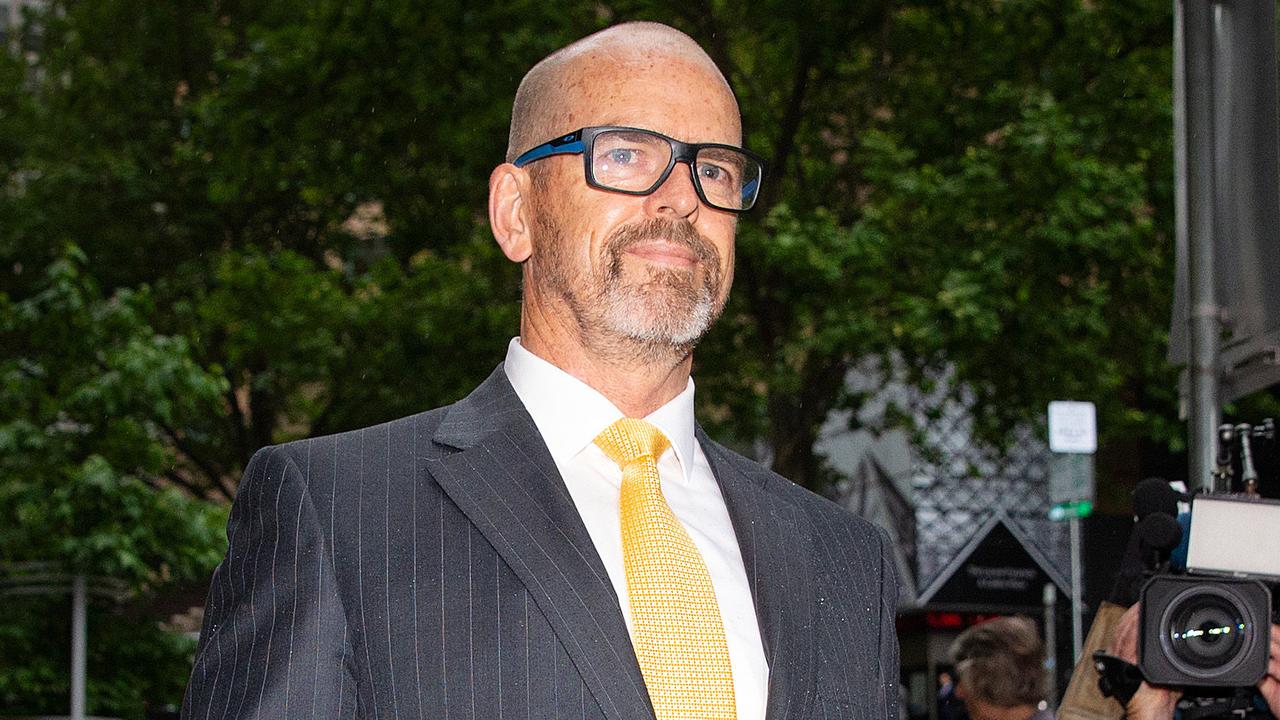

The division is headed by Det-Supt Doug O'Loughlin, who has spent 46 years in the job he joined as a teenage cadet.

When he was in the Special Operations Group, he ran raids on outlaw motorcycle gangs and armed robbers. Now the former action man advocates the science of crime fighting.

The basic skills of ballistics and toolmark examination have not changed remarkably since the force got its first comparison microscope in the 1930s, but its firearms "reference library" now has 4500 weapons, from antique flintlocks to anti-tank guns.

Here is a machine gun seized from a Hells Angels clubhouse, there the little black .32 calibre pistol "Squizzy" Taylor used in his fatal shootout with "Snowy" Cutmore in 1927, yellowed handwritten tag on the trigger guard.

When a bullet - the lead slug or the empty case, or both - is recovered from a crime scene, its origin is checked by test-firing the most likely weapons from the library.

In July 1992, three young people were tied up and shot dead in Burwood. A month later, a man was disarmed while threatening a couple near St Kilda Rd.

When a ballistics expert test-fired the robber's sawn-off rifle, he checked the bullet against those from the Burwood triple murder. It matched.

Ashley Mervyn Coulston was jailed for life and the case is still used as a textbook example of ballistics work.

Fingerprinting started in Victoria in 1903 but since the 1990s computers have transformed the section from a labour-intensive test of memory and eyesight into a modern crime-fighting machine.

When someone is fingerprinted the prints are automatically scanned against the national database of about three million sets.

Are they already "known to police"? Are there any outstanding warrants for the person? And, crucially, are the prints linked to any unsolved crimes?

There are close to a million images from unsolved crime scenes on file, and the computer checks every new set against them. Sometimes they get a "hit".

That's why a drunk driver who has dodged trouble for 20 years might find himself charged with a distant teenage offence. Or a pub brawler gets questioned about why his fingerprints were found at an interstate murder scene long ago.

Memories fade but the system never forgets.

Sgt Steve Dunn says the computers run checks in minutes that would have taken "50 years" when he joined the section in 1988.

Dunn shows off a hi-tech "torch" that throws any colour of the rainbow.

Another favourite machine produces laser light. These show up fingerprints and fluids invisible to the naked eye at the flick of a switch.

"This is CSI stuff," he says.

Stupid crooks are easy targets. When a man robbed a Flemington service station recently, security film showed him touching the glass door, which is why crime scene analysts immediately spotted his palm print.

They had the offender's name within 20 minutes. He was arrested as soon as he got home.

Dunn has a piece of black plastic on the bench. The story is that an alert policeman pulled over a driver because he had plastic protruding from his car boot.

The cop found the boot had been lined with plastic. By the time the police found the body the driver was intending to pick up and dispose of, he was claiming someone else must have put the plastic in his boot.

His story collapsed when a special light showed up his hand print on the plastic.

Then there's the story of the woman who police know was with her lover in Bendigo when a rival truck driver was shot dead in the 1980s. Detectives visited her in Queensland many years later to tell her new tests proved her saliva was on cigarette butts found at the scene.

As Moses said, be sure your sin will find you out. It's in the DNA.