Darcey Freeman thrown from the West Gate Bridge in horrifying murder that still haunts Melbourne

THE first police on the scene after a father threw his own daughter from the West Gate Bridge will never forget the awful day.

True Crime Scene

Don't miss out on the headlines from True Crime Scene. Followed categories will be added to My News.

THE first police on the scene after a father threw his own daughter from the West Gate Bridge will never forget the awful day.

THE hot clock was ticking slowly for the policewomen working Footscray 307 divisional van duties.

It was only 9am - two hours into the duo's shift - but the mercury had already hit 40 plus.

The local police channel was quiet.

The heat was on the cops' side, but would conspire with issues plaguing one man and turn against them.

Reports of a crime too evil to imagine were soon to break across the airwaves.

What had started as a routine shift for Constable Colleen Spiteri and Sen-Constable Tamara Wright was about to turn into a day from hell.

It was the first day of school for the new year; an exciting yet nerve-jangling day for parents ushering little ones off into a big new world.

It was to prove a day too big to handle for a vindictive father with a head full of anger and resentment.

"It was a very hot day and I recall that it was already over 40 degrees by 9am in a week of very high temperatures," Constable Spiteri would recall in a victim impact statement tendered in the Supreme Court.

"We started our shift at 7am and it had been a very quiet morning."

The two policewomen were on foot at Highpoint Shopping Centre when the unbelievable radio call came across at 9.14am.

It was a report of someone seen throwing a child from atop the West Gate Bridge.

Surely not.

Eyewitnesses must have got it wrong.

"I turned to Tamara and said, 'Did you hear that?'" Constable Spiteri said in her statement.

"I could not believe what I was hearing and thought that possibly someone had thrown an item over the side that appeared to resemble a person.

"My thoughts were that no one could do that. Who would throw a child from a bridge?"

ARTHUR Phillip Freeman was an ordinary man with no particular standing in the world, other than within his small circle of friends and in the eyes of those on his side of the family.

A thirty-something "computer nerd good with spanners and tools", according to an unnamed former associate, Freeman was a despondent man.

Commonality had infected every aspect of his life, from his days as a car-tinkering computer geek in university to his lot as a crestfallen dad with not much more to look forward to than weekly tennis games with mates.

A computer science graduate, Freeman had first worked in computer programming and data collection.

"Arthur had a fairly simple life at that stage," his former unnamed associate told this author in 2011.

"Not a lot was expected of him at work. So Arthur enjoyed staying up late. He would be playing Playstation until at least 5am and be ready to head off to work at 8am.

"I am sure that he would catch up for some sleep in his office only to do it again the next night."

Freeman met Peta Barnes in 1998 through friends while employed at Colonial Mutual in Melbourne.

They married a year later on the eve of the new millennium in Perth, where the Barnes family lived.

Less than three weeks after the wedding the two relocated to the United Kingdom.

Their first son was born in February 2002.

A daughter, named Darcey, was born in February 2004.

A second son came along in February 2006.

Freeman and Ms Barnes both had good jobs in England and made several friends, including Aussie expat Elizabeth Lam, with whom Ms Barnes worked.

It was while working as a database administrator for a major company in the UK that Freeman had a brief taste of a life less ordinary.

According to his unnamed former associate, there were fine lunches, wine trips and ski jaunts on exotic mountains.

They were said to have lived in "a nice house" in London "not far from Lord's".

But that all ended when it was decided the family would move back to Melbourne for the sake of the kids' education.

Freeman did not want to uproot and return so quickly without securing a British passport.

One of Freeman's uni mates, with whom he stayed in touch, would later say in a police statement: "Ardy had loved living in England and was living 'the life' over there before he returned."

Elizabeth Lam would tell police: "Arty loved being in England and had mentioned that Peta had dragged him back to Australia just when he had settled into a job that he really enjoyed."

Upon their return to Melbourne, the family moved into a flat in Hawthorn.

Ms Barnes found work quickly. Freeman, however, played the role of a stay-at-home dad.

According to Ms Barnes, she and Freeman experienced "a lot of difficulties" upon their return to Melbourne.

"Arthur struggles with change," she said in her police statement.

"Arthur and I had a lot of arguments."

Freeman's mum, Norma, would regularly check in to see how he was coping.

"I found Arthur was going well," she said in her statement.

"Though with three children and a wife working long hours I thought they sometimes didn't understand each other's positions."

By March 2007, Ms Barnes decided she could no longer live with Freeman.

The two separated.

She said he had personality problems.

"Arthur has quite large mood swings so will go from anger and vengefulness to remorse and back again," she told police.

"Unfortunately it took me until I left him for me to recognise that he may have been suffering a depression of some sort."

She once spoke to her doctor about serious fears.

"I told (the doctor) that I believed (Arthur) would kill my children and that I believed he was vengeful enough to kill my children to get back at me," she recalled in her police statement.

Freeman remained in Hawthorn to stay close to his kids.

On occasion his anger and frustration would boil over.

It happened once when Ms Barnes and her mother, Iris, visited him with their baby son after he asked if they could talk.

"Arthur and I spoke for a couple of hours and it was a complete waste of time," Ms Barnes said in her statement.

"Arthur just wanted to berate me for all of the things that I had done wrong. This had been a consistent theme since I had arrived home from England. Arthur was incredibly resentful in the time since we had come home.

"Mum and I went to leave with the baby and as we were walking out Arthur grabbed the baby off me. I thought he was going to throw him against the fireplace and kill him.

"Mum and I fought him and I bit him to get him to let the baby go because he is incredibly strong and he wouldn't let go."

Police were called, and a shared care arrangement for the children was later put in place.

It was obvious to some that Freeman, regarded by his family as a caring father, was starting to fray at the edges.

"It was a very strange thing that was happening," his dad, Peter, would tell the Supreme Court.

"He had a system going with his dishes and his food and dishwasher - all that stuff was super-efficient. Yet the rest of his life was in confusion.

"He was starting to collect hard rubbish and he would collect every receipt. He had a box full of them in the kitchen … every receipt relating to the children.

"The place was overflowing with toys and clothes and stuff. Norma and I were constantly trying to bring that back into order."

The divorce was finalised in June 2008.

In September, Freeman flew back to England in a bid to secure a British passport.

To his friends over there he seemed depressed, paranoid and emotional.

He returned to Melbourne in late 2008.

According to his unnamed former associate, Freeman muttered some chilling words at a Christmas party that year.

"Arthur and I were discussing things about his children," the former associate told this author.

"During this conversation Arthur said that she (Ms Barnes) 'would regret it' if he lost custody of the children … I am not sure (what he meant), but it did suggest that he would make her life hell."

By the time January 29, 2009, came around, Freeman was an eroded divorcee living his cluttered vanilla existence in Hawthorn.

He was a hunched 35-year-old unemployed computer programmer.

There was nothing special about him, apart from his three shining children - one of whom he was about to kill out of spite for his former wife.

ABOUT 7.30am on the day of Darcey's murder, Freeman packed the three kids and their school holiday gear into his Toyota Land Cruiser at his parents' holiday home at Airey's Inlet.

The kids had spent the last of the school holidays with their paternal grandparents.

His eldest son was already dressed in his school uniform.

It was to be Darcey's first day of school, but she was not ready.

Her school dress and possibly ill-fitting shoes were all back at Freeman's Hawthorn flat, all the way across the West Gate.

Freeman seemed ruffled and agitated.

"He was very distressed," Freeman's father, Peter Freeman, would tell the Supreme Court.

"He looked very tired."

Peter Freeman offered to ride back into town with them, before suggesting an alternate plan.

"I was concerned that Arthur was very stressed and I suggested that the children miss a day of school and stay home," Mr Freeman said in his police statement.

Freeman shook his head.

He had to drop his kids at school in Hawthorn on time.

He knew his former wife would be awaiting their arrival.

"When they left, Arthur was a bit short with me and a little stressed," Norma Freeman said in her police statement.

"But I was in no way concerned for the children's safety."

Freeman rang his sister, Megan Toet, who called him back.

He told her he was worried about what his two eldest kids would have for lunch that day.

"He told me he was worried about being late for school and said he didn't think he was going to make it," Ms Toet told police.

The traffic was terrible by the time Freeman arrived on the bridge.

It was about 9am and the temperature was oppressive.

Freeman was driving against the clock, and still smarting over the outcome of a bitter settlement, negotiated the previous day, that restricted his access to his kids.

According to a female psychologist's report written during the settlement process, Freeman possessed passive/aggressive traits "that seemed to cause chaos around him".

Freeman had not liked the female shrink.

He believed he was "ambushed" during the custody process and painted in an unfair light in the report.

"He felt like he had been set up," Peter Freeman would tell police.

Friend Elizabeth Lam would state: "He said there were lots of angry women (in custody battles) who weren't very supportive of fathers."

The clock inside Freeman's head continued to tick over on the bridge.

It was like a pressure cooker inside the Land Cruiser.

Freeman phoned Ms Lam in England, crying on the phone while telling her he believed he'd lost his children.

He told her there were angry women everywhere he turned.

Ms Lam's phone battery died mid call.

Wondering where her children were, Ms Barnes called Freeman about 8.54am.

He told her to say goodbye to her children, then ended the call.

Ms Barnes rang back, and Freeman answered.

"You'll never see your children again," he said.

Ms Barnes immediately rang her solicitor, the school principal and police.

IT was just after 9am, according to shocked and sickened witnesses, when Freeman pulled up in the inbound emergency lane atop the West Gate.

He had the presence of mind to turn on his hazard lights before asking Darcey to climb over into the front seat.

As cars beetled past his vehicle, he alighted, walked around to the front passenger side, opened the door and lifted his daughter from the vehicle.

He carried her to the railing and hung her over the edge.

Motorist Barry Nelson was driving to work with his wife, Michelle.

He said to her: "Oh my God, I think that guy's going to throw his child off the bridge.'"

Ms Nelson thought the man was just scaring the child and was going to pull her back to safety.

But he didn't. He dropped the little girl.

It would later be determined the killer dad was 58 metres above the water.

"It was like he was holding a bag and tipped it over," Mr Nelson later told police.

"I couldn't believe what I had just seen."

Witnesses watched as Freeman peered over the railing for a few seconds before calmly walking empty-handed back to his vehicle.

"He was walking like he didn't have a care in the world," motorist Greg Cowan said in his statement.

"He just took his time … I couldn't believe what I thought I had seen and it made me feel sick.

"It was surreal."

Mr Nelson was out of his car by that stage and approached Freeman, who said nothing when asked about what he'd just done.

"The overriding impression was he was totally neutral," Mr Nelson later said in the Supreme Court.

"It was just like it was an everyday event, like he may have been posting a letter and was walking back from the post box to his vehicle."

Another witness, Paul Taylor, was trying with shaking hands to dial 000 on his mobile.

An older lady ran up to him and asked: "Did I just see what I thought I saw?"

Michelle Nelson was in denial.

"I started to tell myself it may have been a toy because I didn't want to believe it was a child," Ms Nelson said in her police statement.

"So I got out of the car and looked over the edge. That is when I saw the child's body lying face down on the river.

"I got back in the car and said to my husband, who was on the phone to police, 'It was a child. It's definitely a child.'"

GALLERY: The tragedy in pictures

LISTEN: Arthur Freeman is sentenced

CONSTABLE Spiteri and Sen-Constable Wright responded to the initial radio request from D-24.

"It was too distressing to even contemplate," Spiteri said in her statement.

"I came up on the radio and told the operator that we were on our way and we rushed back to our vehicle. We took the job seriously even though we did not believe the report, but as we were driving towards the bridge we were getting more and more reports from different witnesses and I remember gripping the dashboard in fear of what we would see."

On the bridge, Freeman got back behind the wheel and pulled back into the stream of city-bound traffic.

His eldest son expressed concern for his little sister, suggesting they turn back for Darcey because she couldn't swim.

"Dad would just keep on driving," his son later told police.

"Didn't go back and get her."

In quick time under the bridge, water police motored in to retrieve Darcey's body.

She looked like a doll lying in the water, according to Sgt Alistair Nisbet.

Leading Sen-Constable Andrew Bell swam to her and brought her aboard.

The water cops tried frantically to revive Darcey.

From the shoreline, Constable Spiteri watched one of the officers performing CPR on what was definitely a little girl.

"I remember feeling so overwhelmed by what I was seeing and I turned back towards the footbridge and almost fell to the ground. I cupped my face in my hands and had to tell myself not to fall apart."

Darcey's limp body was passed from the boat to police officers on shore.

Constable Spiteri estimated the little girl was about four years old.

Sen-Constable Wright tried to breathe life back into Darcey's lungs as Constable Spiteri performed chest compressions.

The child's lungs were full of water, but miracles can happen, Constable Spiteri told herself.

They'd happened before.

"During the time I was giving her first aid I completely zoned out," Constable Spiteri recalled in her statement.

"I remember just focusing on the little girl and telling her to breathe … I was probably giving the little girl CPR for about 20 minutes but I began to feel like I had known her for years.

"I could feel that she had a strong soul, and felt such a strong connection with her."

It took the force of a medical helicopter landing nearby to wrench Constable Spiteri back into the world around her.

"I got a face full of dust," she recalled.

"It was almost like breaking a trance. It was then that I noticed there were several police officers around me."

She continued with the chest compressions as a paramedic intubated the girl.

Paramedic Kristine Gough was working on her birthday that day.

She told Darcey to fight, to hold on and survive, as the medical battle continued.

"I have performed CPR on hundreds," Ms Gough said in her victim impact statement, "but this was the only time I can recall talking to my patient, as if my words of 'don't give up on me' would make a difference.

"I begged her to not give up."

Darcey was airlifted to the Royal Children's Hospital.

ARTHUR Freeman, meanwhile, had driven his boys into the city.

He parked his vehicle.

Carrying his baby boy and with his other son beside him, he shuffled his way into the Commonwealth Law Court building at the corner of William and La Trobe Sts.

He tried to hand his youngest to one of the security guards.

"He seemed quite stressed and was visibly shaking," guard Brian Skilton would describe.

Freeman began to cry.

The police were called in.

When Sen-Constable Shaun Hill and his offsider arrived, Freeman was sitting in a chair outside witness room 25.

With head in hands, the big man was bawling and rocking back and forth.

The baby boy had been taken to a room to have his nappy changed.

His other son remained with his father; the innocent young kid not fully understanding the gravity of the horrendous situation.

Freeman did not respond to questions put to him.

Sen-Constable Hill turned his attentions to the boy standing next to the silent man.

"What's your name buddy? Is this your dad?"

"Yeah."

"Are you and your brother OK?"

"Yep."

Sen-Constable Hill turned back to Freeman.

"What's happened?"

Freeman stood.

"Take me away," he mumbled, sobbing even harder.

Across town at the Royal Children's Hospital, doctors were working to revive Darcey. Constable Spiteri and Sen-Constable Wright were present.

"We stayed in the room while she was being worked on and she started to breathe a little on her own," Constable Spiteri stated.

"This is the first time I broke down. I went into a room to the side and I cried so hard. I kept thinking, 'What were this child's last thoughts?"

Peta Barnes arrived at the hospital.

Constable Spiteri briefly spoke with her.

It was not police talk straight from the operating manual.

"I told (Ms Barnes) that her daughter was strong and fought hard. I told her that in the short time I was with (Darcey) I loved her, so she had love around her.

"I told her that she had the best care we could provide."

Doctors allowed Ms Barnes time alone with Darcey.

The four-year-old did not survive.

"We were picked up from the hospital when little Darcey was taken for brain scans and I found out later that she had passed away in her mother's arms after being pronounced brain dead," Constable Spiteri said.

In a homicide squad interview room that day, a snivelling Freeman remained mute and non-responsive.

He was deemed unfit to be interviewed.

His parents arrived and were given time with him.

"He didn't say anything and was in a psychiatric state that I have never seen him in before," Mr Freeman later told the Supreme Court.

"He was all hunched up, down on the ground … like a newborn child. With no communication: no reception to anything that we would say."

He was to be charged with murder.

In the days that followed, Constable Spiteri and paramedic Gough felt compelled to attend Darcey's funeral.

"I fought the tears (at the service)," Constable Spiteri explained in her statement.

"I am a police officer and I am supposed to deal with these situations. It's part of our job. You know, you need to be unemotional and move on and be strong. I couldn't."

She had to move police stations to get away from the bridge and the emotions it stirred.

"Other police officers say it was the worst day of their career, and they weren't even there."

Ms Gough said in her statement: "I have been to dead children before - SIDS, accidents and suicide - but nothing has impacted me more emotionally than this incident."

It was not until March 2009 when Freeman went to trial.

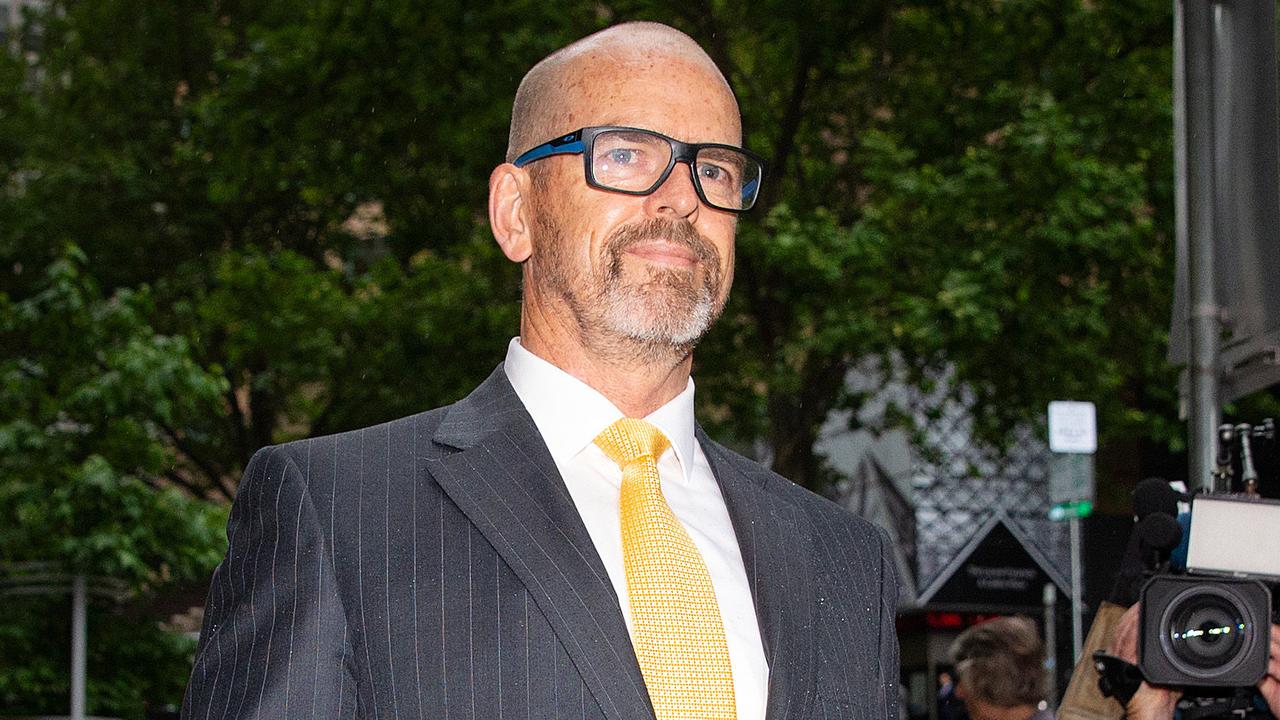

Despite wearing a suit and tie, he presented - with a bushy beard and tufts of unkempt hair - like a mentally windswept man.

Chief Crown prosecutor Gavin Silbert, SC, suggested he'd adopted the "Rasputin-like appearance of a mad monk" to assist his defence argument.

His barrister, David Brustman, SC, gave the jury a simple choice: was Arthur Phillip Freeman bad or was he mad?

It was the defence case that Freeman had acted in a "dissociative state", like a sleepwalker, when he killed his daughter.

Only one of six psychiatrists who assessed Freeman agreed with that proposition.

Psychiatrists called as prosecution witnesses said Freeman had done enough things on the day to dispel any suggestion of a psychotic mental illness.

He organised his kids for the journey, drove from Airey's Inlet to Melbourne, made and received telephone calls, turned on his hazard lights and parked properly in the CBD.

It was a case of "spousal revenge", the jury was told.

Mr Silbert told the jury: "Freeman was upset. He was angry. The threat to Peta Barnes in the two phone conversations related by her indicate that his anger management problems were about to bubble over.

"What it amounts to, ladies and gentlemen, is that in a paroxysm of anger with Peta Barnes he stopped on the bridge and threw Darcey over the rail.

"The threats to Peta Barnes minutes before the murder demonstrate he knew the nature and quality of what he was about to do. We are perhaps indeed fortunate that he didn't throw all three children over the bridge."

The jury returned with a guilty verdict.

During the subsequent pre-sentence plea hearing, Peta Barnes broke down while trying to read out her own victim impact statement.

Crown prosecutor Diana Piekusis had to read it aloud for her.

"Since the loss of Darcey I grieve on a daily basis and realistically do not see how that can ever change," the statement said.

"The saying 'time heals all wounds' is not true for myself and I don't ever expect it to be. Not a day goes by where I do not constantly think of Darcey; where I don't miss her and wish with all my heart that she was with me.

"I can feel her little hand holding mine when I walk down the street or drive in the car. I lie in bed at night and hold her in my arms. I talk to her and think of her daily.

"I can never erase from my mind the thought of my beautiful girl so willingly and trustingly going to her father at his request on top of the West Gate Bridge. Of her falling to her death and what her last thoughts must have been.

"The nightmares and sleep deprivation I suffer around this are too horrific to detail."

Ms Barnes also spoke of her heartbreak at the hospital.

"No one can erase the thoughts and associated feelings I have of sitting in the hospital and having to tell the staff that they were allowed to turn the life-support machine off.

"Or of holding Darcey in my arms as she passed away and knowing that this decision would take her from me, and knowing that there was no other option available to me."

Justice Paul Coghlan sentenced the killer dad to life in jail with a 32-year minimum.

"The motive which existed for the killing had nothing to do with the innocent victim," Justice Coghlan said.

"It can only be concluded that you used your daughter in an attempt to hurt your former wife as profoundly as possible. You chose a place for the commission of your crime which was remarkably public and which would have the most dramatic impact.

"It follows that you brought the broader community into this case in a way that has been rarely, if ever, seen before. It offends our collective conscience."

In her statement, officer Spiteri said she expected the incident - and Darcey's last imagined thoughts - would continue to haunt her.

"It breaks my heart," she said in her statement.

"I cannot understand why this happened."

First published in January 2014.