Book extract: psychoanalysing Alphonse Gangitano

ONLY months before his murder, one of Melbourne’s most notorious gangsters sat down with psychologist Tim Watson-Munro to get a few things off his chest.

I FIRST learned that Alphonse Gangitano had been murdered on the 6pm news. He had been my client for a number of years, although it had been several months since I’d last seen him on a professional basis. I had been kept abreast of his life though, thanks to regular media items about his alleged behaviour in and around Melbourne.

Gangitano had been due to face a tough committal hearing a day or so after his death, arising from allegations that he and Jason Moran had viciously attacked a number of patrons at the Sports Bar nightclub.

This club is situated in the notorious King St district of inner Melbourne, a place where piss and bad manners occasionally clash with fatal results. The alleged offences had occurred quite some time beforehand. Both men had entered pleas of not guilty, and true to the form that I had come to know over the years, Gangitano had bunkered down for what was expected to be a long legal fight.

His very able barrister, Lillian Lieder QC, must have had some form of premonition the day before his death – by her account she had told him to take care and to watch his back. He should have listened to her because within 48 hours he lay dead, ambushed in his own home to die in the family laundry. His assassin had demonstrated a callous disregard for the unspoken rule that you never involve the wife and children in such business. For it was Gangitano’s wife, Virginia, in the company of their two young daughters, who found him lying in a pool of blood with three shots to the head.

They had been out for the night visiting friends while Gangitano stayed home to relax. He was evidently in his underwear when his murderer struck. The police felt that Gangitano must have known his killer. How else, they reasoned, would the killer have gained such ready access to Gangitano’s well-fortified Melbourne home?

Without doubt, Alphonse Gangitano was a tough man. He had a fearsome reputation among his enemies – some people referred to him as the Godfather – but he was unswervingly loyal to his friends. I had heard on the grapevine that some in the underworld were concerned about his increasingly erratic behaviour. There was talk of a drug problem.

Even so, I was genuinely shocked to hear of his death that January night in 1998.

Gangitano had first been referred to me by his solicitor George Defteros.

By the time he contacted me, Gangitano had been arrested and charged with the murder of Gregory Workman. It was claimed that Workman had died from multiple gunshot wounds that had been inflicted at close quarters following a heated exchange at an inner city party.

He was facing a very serious charge and only some form of special medical or psychological circumstance would allow him any chance of successfully applying for bail. I prayed Gangitano would not blame me if he were required to remain in prison for a while.

Gangitano was flipping out in B Division, a notoriously tough wing within the Pentridge Prison complex. His behaviour was erratic and he was spooking not only the other prisoners, but also some of the guards.

EXTRACT: WHEN THE SOG COULD HAVE TAKEN DOWN MARTIN BRYANT

He was refusing to come out of his cell, preferring instead to strut about in his jocks. He was also not eating. I suspected that the screws would be glad of my involvement. While being tough men in their own right, the prison officers were no match for Gangitano and his reputation. Forcing Gangitano to do something could mean encountering a balaclava-wearing, baseball bat-carrying thug in the driveway of their home in the early hours.

‘I’ll see him tomorrow, George,’ I advised. I needed time to prepare for the meeting, and besides, it was already mid-afternoon. It was unlikely that I would gain entry to the prison at such a late hour of the day.

By the time I arrived the following morning, matters had deteriorated. The guards were toey and one or two of the greener recruits had rather jaundiced complexions. They knew of the Godfather and were not about to f--- with him just for the sake of their careers.

‘Tim Watson-Munro,’ I announced with outstretched hand as Gangitano was eventually led into the interview room.

‘Good to see you, mate. I know who you are. I’ve heard a lot of good things about you,’ he said with a grin.

‘Well, I hope that I can be of some good to you, mate,’ I replied. So far the rapport between us was reasonable.

‘Can you get us out of this f---’n s------?’ he said in a more sombre tone. ‘The joint’s driving me nuts.’

‘Tell me more about it, Al,’ I said. It was corny but it worked. A powerfully built man, Gangitano’s ability with his fists was the stuff of legends. He was fidgety and yet I sensed that he was keen to co-operate. His black eyes, encased by equally dark rings, projected an understated menace. No doubt he had endured many sleepless nights since the time of his arrest. He was distracted. His glazed expression and the poorly controlled agitation in his voice said it all. Beyond his initial enthusiasm, the conversation dwindled.

I suspected that he was depressed and slowly trying to come to terms with the magnitude of his situation. I had worked with dozens of gangsters over the years and yet there was something about Gangitano’s presence that made me momentarily feel that I was out of my depth. If I was to maintain his fledgling faith in me, considerable clinical skill would be required.

EXTRACT: THE VIC MARKET MAFIA WARS

As he gave me a potted history of his life, every few minutes or so the train of Gangitano’s thoughts were interrupted by the concerned stares of a prison guard peering through the office window. He had been posted there to ensure my safety.

Alphonse’s late father, Phillip Gangitano, was a well-respected Italian businessman who had worked out of Lygon Street in Carlton. Situated between the leafy Melbourne University precinct and the central business district, Carlton is the city’s ‘Italian Quarter’. When I first shifted from Sydney, I lived in Carlton for several years before moving on. I loved the vibrant atmosphere created by its plentiful restaurants, cafes and music stores.

Carlton was Alphonse’s playground as a child, while he accompanied his father on his rounds. He described a strong respect and love for his father, who by his account could be a strict disciplinarian but otherwise doted on Alphonse and his sister. He was greatly affected by his father’s death, which had occurred not long before his current troubles. His expressions of sadness when describing the loss of his father reflected a softer, more sensitive edge to his personality.

He also described a profound love for his mother, who at the time was still alive. I realised that Gangitano was about my age.

He received a privileged education attending the De La Salle and Marcellin colleges. His father evidently had big plans for his son which did not, by Gangitano’s account, mesh terribly well with his own.

‘Where’s all this heading?’ he suddenly growled.

It was clear that he was uncomfortable talking about his early childhood. This was personal stuff and he could not see how it was relevant. This reaction was not uncommon.

More often than not over the years, I had found that men in prison charged with serious offences could not see the point in talking about long-past events in their life. They wanted an urgent resolution of their immediate problems and could become openly hostile if pushed to provide me with this type of detail.

And yet it was essential for me to obtain as much clinical and social information about their lives as I could in order to formulate ideas about when and how their psychological problems had started.

It was also vital to my credibility in the witness box.

I had learned years earlier that the omission of one important aspect to a person’s history could spell disaster under cross-examination. This was especially so with Gangitano, where I knew that the gloves would be off in any application for him to be released on bail.

I did my best to explain this and he relaxed somewhat but, sensing his impatience, I then moved on to more current issues. It was clear that he was ‘doing it hard’ in prison. He was severely depressed and highly anxious regarding the future.

He reported that he had managed to avoid any physical confrontation but felt that it was just a matter of time. Greg Workman had friends who were doing time, and the possibility of some jailhouse justice was always just around the corner.

‘Some c--- will have a go,’ he sighed.

Sensing his apparent despair, I asked him if he’d ever felt this low before.

‘Yeah, I saw a psychiatrist at St Vincent’s a while back,’ he said.

I was taken aback by his candour. It seemed that, despite his earlier bristling, we were getting somewhere. A prior history of treatment was relevant and possibly helpful to his case, as it reflected a desire to receive help. I sensed that, despite his reputation, I was dealing with an intelligent man who was capable of insight and reflection, two essential ingredients for successful psychotherapy. This case was becoming more interesting by the minute.

As expected, Gangitano’s application to be released on bail was unsuccessful. He was, after all, charged with a capital crime. The judge was unmoved by strong evidence concerning Gangitano’s deteriorating mental state in prison, as well as his prior psychiatric history, which had involved specialist treat- ment for depression, anxiety and serious bowel issues.

Short of a miracle, Gangitano was now destined to spend at least the next year or so in custody. And if he went down at trial he probably wouldn’t see freedom for a couple more decades after that. I had been around long enough to know that, in certain circumstances, miracles do happen.

Gangitano’s miracle took the form of an announcement by the Crown at a preliminary hearing that their star witnesses had fled the country and were unlikely to ever return. One could only speculate as to the reasons behind their decision to take flight. As a consequence, the Crown advised they would have no evidence to lead of a material nature. The prisoner was free to go.

‘F----n amazing,’ Gangitano said with a chuckle as he left the court.

I fully expected that his interest in exploring his life with me would rapidly dissipate now that he was free. But shortly after his release, he contacted me to schedule an appointment. It seemed as though some slow progress had occurred.

My next session with Gangitano was at my St Kilda Road office. Dressed in an Armani suit with an elegantly co-ordinated tie, he cut a striking figure. But his attire camouflaged the silent danger impatiently lurking within.

‘Hard to believe you were on the bones of your arse in Pentridge such a short time ago,’ I mused as I ushered him into my office.

He cut straight to the chase. ‘Look, mate, I want to come and see you, I can talk to you, but I’m not comfortable sitting out there in the waiting area with all those f----n loons and crooks.’

I realised immediately that he was concerned about maintaining his image and suggested that it might be better for us to meet on a regular basis over coffee. I knew that some clients preferred the informality of discussing their problems outside the confines of an office. Indeed, some of my best work during my Parramatta days had been accomplished not in my poky office but while I walked the rounds of the prison. ‘I could use the fresh air,’ I joked, and he relaxed straightaway. The next hour was fruitfully spent at the deli across the road from my practice.

For a time we enjoyed regular meetings and I came to know Gangitano better. He was a complex man. The allegations regarding his behaviour over the years were seemingly endless – standover merchant, hit man, drug trader. His criminal history, involving guns and repeated acts of bloodied violence, was appalling. When he was referred to me he had been charged with a vicious and cowardly murder – shooting an unarmed man at point-blank range. And yet these were issues which neither of us really wanted to explore in any depth. I was far more interested in the positive aspects to his personality, which I sensed at some level he was keen to harness.

At one session he spoke rather wistfully about his unutilised potential. ‘I might have been a lawyer, you know,’ he volunteered. Certainly by this stage I knew that he had the intellectual prowess to have made this happen had his life evolved differently.

Our discussions were far-reaching. He enjoyed literature and music. He was certainly well read – he particularly loved Oscar Wilde – and told me that he liked to visit bookshops in his spare time. He spoke at length of his love for his family, particularly his two little girls. On one occasion when I walked with him to his car I couldn’t fail to notice a child’s booster seat meticulously strapped to the back seat. It was a poignant moment, reminding me powerfully that whatever people do for a quid, they can have other lives that are seemingly quite normal.

There were times when the ambience between us was prickly. This was usually after Gangitano had enjoyed a night of drinking.

Years of dealing with angry men had taught me to recognise the signs – in Gangitano’s case the ubiquitous black rings under his eyes and a pasty complexion. These physical signs, along with short, sharp responses to my questions – ‘Jeez, you get f----n paid for this, mate?’ – would generally be sufficient warning for me to back off. ‘Leave it till next time,’ I would silently decide.

We had discussed Gangitano’s legendary temper from time to time. Indeed, much of my work with him focused on equip- ping him with skills to better manage his anger. His alleged criminal offences over the years had often been a direct conse- quence of his hairpin fuse. He knew he had a problem and he knew alcohol was a major trigger.

It was a matter of teaching him to recognise the signs of escalating tension long before critical mass was reached. I tried to convince him this would provide him with valuable choices, rather than him reaching a point of no return with his anger, as had so often been the case in the past.

But he loved a drink and he loved to party. It was a potentially lethal mix – more so for any hapless citizen who might, through unfettered misfortune, cross his path at such times. A volatile combination of alcohol and attitude, either projected or perceived, would invariably lead to some sort of altercation, with violent outcomes. And so, before too long, Gangitano was back in trouble.

In the pre-dawn on a deserted inner-city boulevard, a hapless driver drove into the rear of Gangitano’s car. The unlucky bloke then decided to alight from his vehicle to remonstrate. Push led to shove before Gangitano allegedly threatened to hunt the bloke down and kill him – not the first time he had allegedly threatened to take another’s life in a fit of rage. This was far more serious than your average episode of road rage. In the end, although the local police became involved, the traumatised driver decided not to pursue the complaint. Although he may have been careless behind the wheel, he was far more focused when it came to his personal safety.

I came to appreciate the importance of cultural considerations when dealing with men like Gangitano.

This related not so much to his Italian background, but to the subculture in which he was so immersed. It was a near-impossible dream that he could ever successfully extricate himself from his peers. His whole identity was integrally wound up in his so-called gangster lifestyle. His progress hence became a matter of attaining realistic goals. I reasoned that, even if he only utilised some of the insights and practical skills he had acquired through me on the odd occasion, then my involvement was worth it.

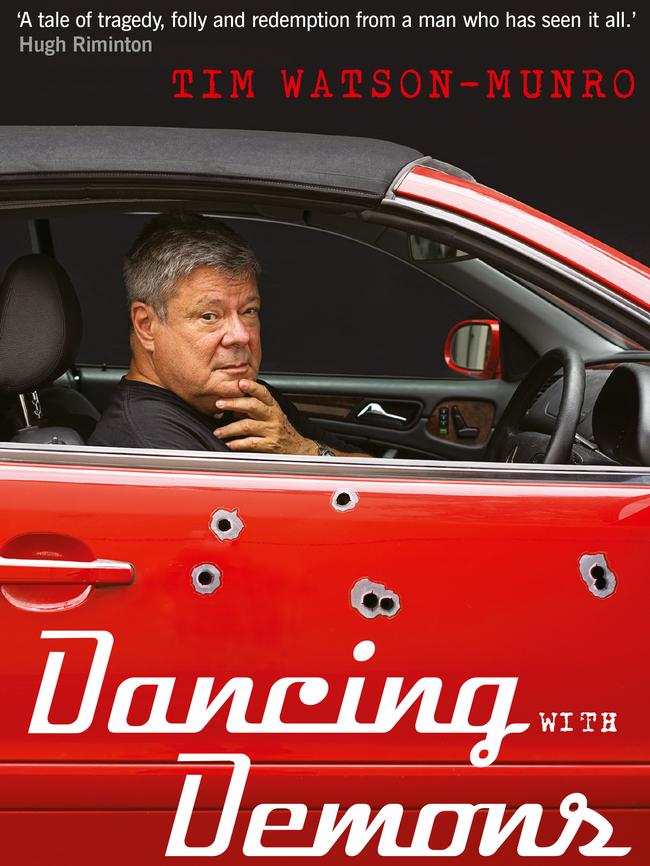

This is an edited extract from Dancing with Demons by Tim Watson-Munro, published by Macmillan Australia, RRP $34.99, available in all good bookstores now. http://www.panmacmillan.com.au/9781760552664/