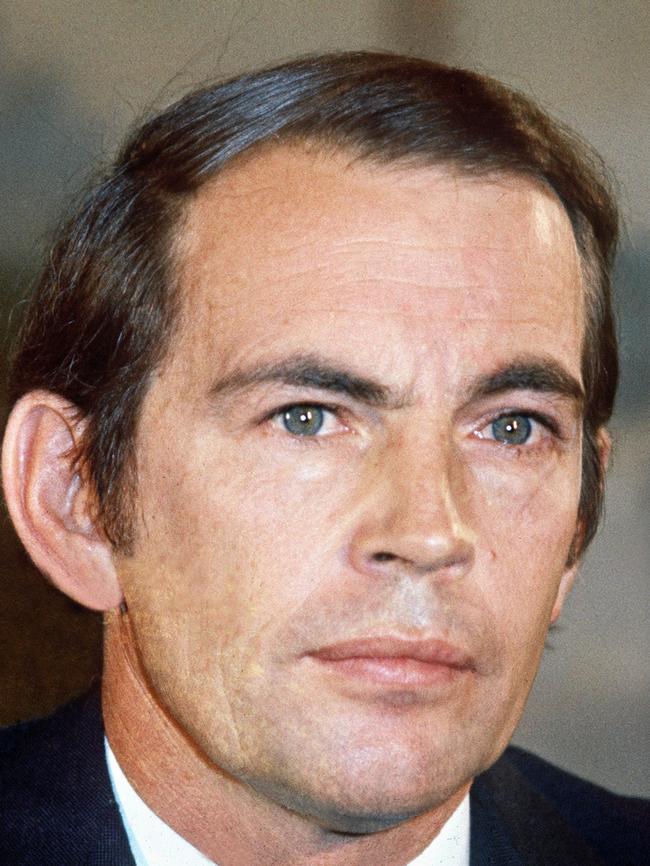

Heart transplant pioneer, Christiaan Barnard, became as famous for breaking hearts as he did for mending them

South African heart transplant pioneer Christiaan Barnard became as famous for breaking hearts as he did for mending them in the decades after his controversial operation at Groote Schuur Hospital in Cape Town 50 years ago tomorrow.

Today in History

Don't miss out on the headlines from Today in History. Followed categories will be added to My News.

REGULAR sex, preferably in a romantic relationship, is the best way to keep a healthy heart, advised South African heart transplant pioneer Christiaan Barnard.

In following his own advice, Barnard became as famous for breaking hearts as he did for mending them in the decades after his controversial operation at Groote Schuur Hospital in Cape Town 50 years ago, on December 3, 1967.

Thrice married, twice to women younger than his daughter Deirdre, Barnard also boasted of a liaison with Italian movie star Gina Lollobrigida.

Between his turbulent romances, and extramarital affairs that began in his first marriage to cardiac nurse Alette, during US studies in the 1950s, Barnard built a leading cardiac unit at Cape Town. He also pioneered open-heart surgery before undertaking the heart transplant procedure theorised by European and US cardiac surgeons.

With funds from his autobiography, released in 1969, he also established The Chris Barnard Foundation in Austria, dedicated to providing medical care and operations for sick children from developing countries.

Support from the foundation extended from heart-related ailments to care for Aids orphans in Zimbabwe and children affected by the aftermath of the 1986 Chernobyl nuclear disaster.

Born in 1922 in Beaufort West village in South Africa, his father Adam was a Dutch Reformed Church minister and missionary to mixed-race communities. Although money was tight, Barnard and his three brothers were encouraged to pursue their ambitions by mother Maria. Barnard studied medicine at the University of Cape Town Medical School, where he graduated in 1945.

After an internship and residency at Groote Schuur Hospital, he worked as a general practitioner in rural Ceres.

He then joined the university medical school research staff, gaining recognition for work on gastrointestinal conditions. He secured a scholarship in 1956 to complete a PhD at Minnesota Medical School, which then concentrated on heart surgery. Lured from gastrointestinal interests after performing his first heart operation in Minneapolis, Barnard returned to Cape Town University medical school in 1956 as director of surgical research.

His sometimes controversial work included transplanting a second head on to a dog in 1960, after visiting the Soviet Union to discuss the process with surgeons who had already done the operation. As associate professor at Cape Town University from 1962, his research interests were wideranging.

Assisted by a lung-heart machine donated by the US, Barnard developed a world-standard heart surgery unit. Writing papers about the possibility of heart transplants, he noted the difficulty of timing in finding a donor.

His younger brother Marius also joined the Groote Schuur cardiac unit, where he helped his brother transplant 48 dog hearts, a fraction of the number completed by US surgeons then on the verge of a human transplant. Marius was on the surgical team who worked with Barnard to remove the heart of accident victim Denise Darvall, 25. She was on life support when doctors Coert Venter and Bertie Bosman told her father Edward she was brain dead and they could do nothing more. But Bosman explained there was a man who might be able to help, if Edward would allow them to transplant Denise’s heart. Darvall later said he thought only of his daughter in the four minutes it took him to decide.

Barnard still faced an ethical dilemma, as death could only be declared by whole-body standards. Although Denise’s brain was damaged, her heart was healthy; Marius revealed 40 years later that he urged Barnard to inject potassium into Denise’s heart to paralyse it, rendering her technically dead. Her heart was placed into grocer Louis Washkansky, 53, who died 18 days later from pneumonia brought on by drugs designed to suppress rejection of his new heart.

On January 2, 1968 Barnard performed his second heart transplant. The recipient was retired dentist Philip Blaiberg, 58. The donor was coloured stroke victim Clive Haupt, 24. Transplanting the heart of a coloured man to a white in South Africa aroused racial controversy, but kept Blaiberg alive for 18 months. Barnard’s sixth transplant patient, Dirk Van Zyl, survived 23 years. Between December 1967 and November 1974, 10 heart transplants were performed, as well as a heart and lung transplant, at Groote Schuur Hospital.

Barnard pioneered another technique in 1975 when he inserted the heart of a 10-year-old accident victim into engineer Ivan Taylor, 58, alongside his own heart. Barnard described the operation as adding a “permanent assistant” to Taylor’s crippled heart.

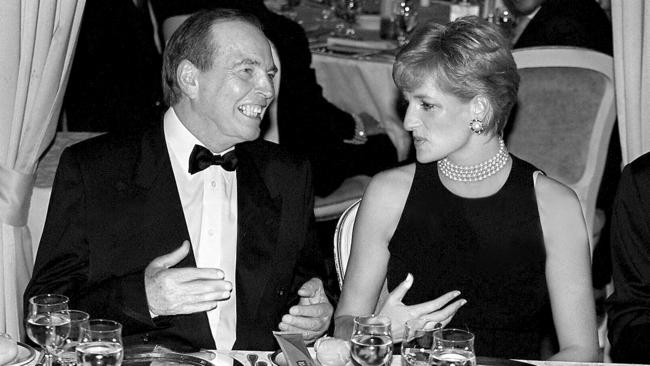

By the time worsening rheumatoid arthritis in his hands forced Barnard to retire from surgery in 1983, his celebrity status had secured introductions to Princess Grace of Monaco, actor Sophia Loren, and Princess Diana.

Living between Austria and South Africa and died from asthma in 2001.

Originally published as Heart transplant pioneer, Christiaan Barnard, became as famous for breaking hearts as he did for mending them