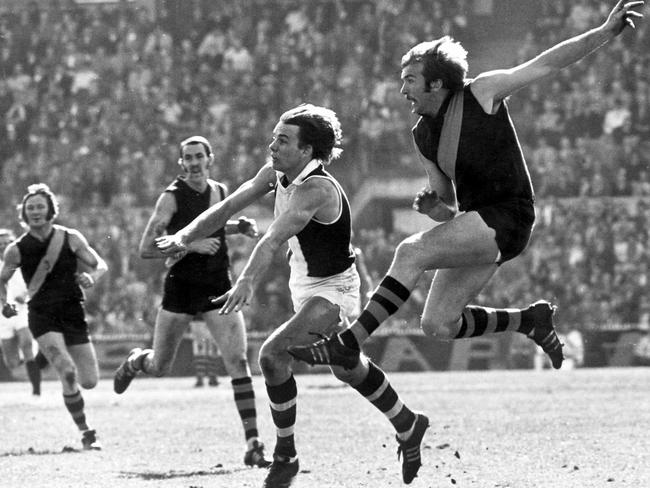

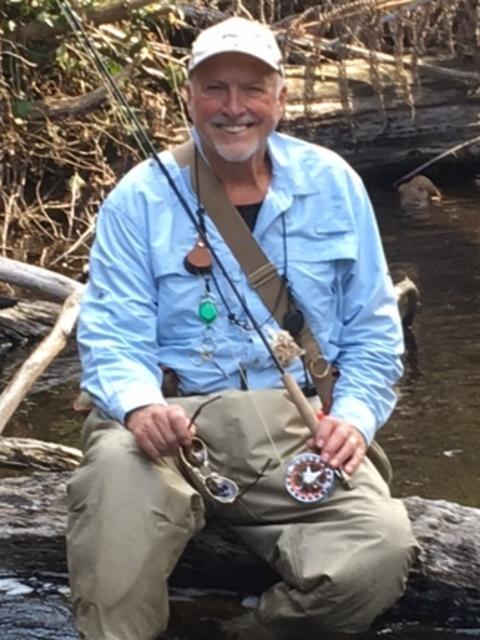

Hamish McLachlan: Popular broadcaster Rex Hunt on fishing, footy and family

BROADCASTER Rex Hunt had many terrifying moments in his former job as a policeman, but the events of one night still send a shiver down his spine.

News

Don't miss out on the headlines from News . Followed categories will be added to My News.

REX Hunt. Two-time premiership Tiger. Policeman. Fisherman. Broadcaster. Rex introduced a style of commentary which was unique to football. His excitement and his humour, whether talking about footy or fishing, earnt him recognition and stardom. We spoke about being shy as a child, why he found the police force too confronting, ignoring the critics and the origin of “Yaaableettt!”.

HM: Were you bullied as a kid at school?

RH: I wouldn’t say bullied, but I was made to feel very ordinary and inferior to some of the smarties who could pass exams with their great memories. Or who could play football and cricket better than I could. I was always bottom of the class.

HM: You said you were made to feel inferior. Did that mean you went into your shell at school?

RH: I did a little bit, until I was among people who I was comfortable with. On the Mordialloc Pier fishing for garfish or in the creek trapping shrimps. I was fanatical about learning that in nature, everything is there for a reason. From then on, I was very confident of myself and my ability to do well.

My message to kids today is to find something you love doing and then get paid for it. And just because you’re bottom of the class doesn’t mean you can’t buy the school. Things changed in my mid-teens when I grew three or four inches taller in one year. I started to take these big marks, and I started to develop the two greatest things known to mankind: confidence and self-belief. I started to stand out with football and cricket, and then I really started to enjoy my life.

HM: When did you first discover your love of fishing?

RH: The year of the Olympics in 1956, on the Mentone Pier, which has long been demolished. I can remember going along and watching the old guys. There was a guy called Harold George, who didn’t have any legs. He wore a white apron to protect his clothing from the flour that he made his dough bait from. I remember him pointing out the garfish in the waves. He rigged my line and I caught a beauty I took it home to my mum. The great thing about me now in my later years is that I can pass all this knowledge on to the kids.

HM: You didn’t have a lot growing up, did you?

RH: Middle class was upper class for our family. Bubble and squeak and hand-me-downs were the norm. My father worked very hard; he was a labourer. They talk about mums having it easy, but now I realise, having watched my wife and my daughter bringing up kids, that constant home duties is a pretty tough job. We had just enough money to live from week to week, and you know what, I appreciate it, because you never forget where you’ve come from.

HM: When did you feel the police force was for you?

RH: After a discussion with my mother and father, who said, after I repeated year 9, “What do you think you’re going to end up doing? You’re going to end up doing nothing!” We were discussing vocations and I said that I liked the outdoors. My mother thought it would be a good idea if I was to become a surveyor, and my father wanted me to become a bricklayer and to get a trade, or something along those lines. Then my mother said, “Well, what about a policeman? I think you’d look good in a uniform!” I took her advice, and the next year I joined the Vic Police Cadets. I later found out Dad was rapt because he thought I could fix a parking ticket.

HM: You were a sergeant by the time you were 30?

RH: I was. I worked my way through the ranks. Crime car squad, CIB, company fraud squad and uniform. I’m very proud, Hamish, to say that during my 200-game league career, not once did I get any preferential treatment in the force. Well, I tell a lie … the only preferential treatment I can recall was when my boss, a lovely man by the name of Inspector Bill Gooding, came in at 4 o’clock one morning on a night shift, after I’d just locked up a crook.

I was having a cup of tea, and he said, “Why don’t you go home young man, and get a little bit of sleep.” I said “That’s very nice of you sir, but why are you doing that?” He said, “Because the Saints have to win tomorrow, and we’re playing Collingwood!” It was fantastic. And we beat the Pies. And Bill got his three hours back the next week when I stayed on and helped him raid an armed robber’s joint in Port Melbourne. He had a double nightmare, this bloke; he barracked for the Pies.

HM: Did you have any terrifying moments as a policeman?

RH: Quite a few. One was outside the Prince of Wales Hotel in St Kilda. We were called down there because there was a bunch of blokes who had bailed up a couple of young coppers. I grabbed a couple of senior men from the watch house and we charged down there. When we arrived, I went straight over to a couple of meat-heads and sorted the biggest and loudest one out with my baton. I was knocked over the head with something heavy. My gun was taken from me. I went around the corner and a bloke fired the gun at me. I can still remember seeing the flash of the .32 as it went off. I suppose I’m very lucky, unlike other policemen, to be here today talking to you about it. Thinking about it sends a shiver down my spine.

HM: Why did you quit the force?

RH: In the end, it was because I wasn’t mentally tough enough. When I was a sergeant at St Kilda, I got a call at about midnight from the young constable at Chelsea who said there’d been a domestic argument down at Bonbeach. There was a guy who told his wife he was taking his car to find the first tram and he was going to commit suicide. I can remember putting the phone down, and getting a call from D.24 Police Headquarters, that a Holden sedan had collided with a stationery tram in Carlisle St.

I went down there, and I don’t even want to describe what I saw, because I just couldn’t believe it. I remember I went home early that morning and my wife, Lynne, saw I was very upset. She asked me what happened, and I said that I just didn’t want to talk about it. That same year I’d had a young boy die in my arms as a result of a swimming pool accident. I had to give a death message to parents of a young kid who was run over by a drunk. It was too much. Everything about my job dealt with people’s misfortunes. I had to get out.

HM: You’ve got tears in your eyes — you’re still affected by those stories.

RH: Well, I’ve got granddaughters, six and eight years old, and no matter how hard a policeman you think you are, it’s still someone’s kid, and that breaks anyone’s heart. It takes a very special person to work at a job like that and not take it home. I admire the men and women of the Force so much. They do a wonderful job.

HM: And the TV and radio has gone so well, a policeman on a pedestrian crossing in London recognised you?

RH: Lynne and I were going to Harrods to have a glass of champagne and some oysters. We were walking across the street and the London bobby said, “Ooooh, yabba dabba doo, Guv! Kiss the fish, Guv!” I said, “It’s yibbida yibbida, you idiot, but that’ll do.”

HM: It just took off to a point where the “Rexisms” started to emerge. Has the environment changed so much that you couldn’t do it now?

RH: You can’t do it now; it was a different era. That was then and this is now, so to speak.

HM: Did you know how far you could push it?

RH: I had to read the situation pretty carefully. Some people mightn’t think it, but I do have common sense, which isn’t that common, Sam Newman tells me. The defining moment came at the first bounce of the 1989 grand final, when I said, “Bourke knocked it to Bews, handpassed to Bairstow, on to Brownless, and here comes, Yabbbbbleeettt! And Dermott Brereton’s down in the centre of the ground looking like a freshly killed sheep!

Ron Barassi, this is magnificent!” Ron said, “Well I don’t know about it being magnificent, Rex, my eyes were down on the ground, I dropped my pen at the first bounce!” Sam Newman said, “You idiot, Ron!”, and we were off and running.

It was just amazing in those ensuing years, even at Waverley. The best example was when you had the broadcast box in the middle of the outer. There were thousands of people around it with the window open, listening to us. At that particular time, it was a buzz. If people keep telling you how good you are, you start to believe it. Every now and again you get ahead of yourself, and I might sometimes get a bit ahead of myself, but I’m pretty happy now when people pull me up on the street or down at the beach when I’m walking.

HM: People deal with fame differently. What did you find the most difficult?

The intrusion of my private life, particularly on my family. You couldn’t go out to dinner anywhere without it becoming a circus. Everything became about me, it was always about me, and in the end, it placed an enormous amount of pressure on the people you love the most. But if you put yourself out there you have to take the knocks as well as the accolades. Public life does come at a price.

HM: If you own a public face, you need to have a thick skin.

You’ve got to have a thick skin where people who you think you can trust are scheming, planning behind your back, and then can actually look you in the eye and tell you the opposite, when you know that things are going to happen. It’s disappointing. I tell young folk looking to get into the media: even if some people have never met you, they will hate you anyway. If no one hates you, aren’t doing much right.

HM: Do you remember why you said “yibbida yibbida” for the first time?

RH: Yeah, I do. It was on my first television program, in a very swollen and discoloured Goulburn River. I was with my chocolate Labrador Missy, and I knew that I could catch a rainbow trout if I really tried. I’d been digging for some scrub worms, getting the camera in and looking at the scrubs worms and all that sort of stuff. I said that it was fantastic, and eventually said “Yibbida yibbida, that’s all, folks!”.

I remember I went fishing two days later with my dear departed friend Neil Thompson, and he said to me, “If your best friend can’t tell you, no one can. You’re making a fool of yourself, stop kissing fish. What does the f---ing yibbida yibbida mean?” He was 20 years older than me. I think for the next three years in Kmart we sold over 100,000 yibbida yibbida beanies in the Australian winter. Thommo came to me and said, “I’ll just stick to putting the bait on the hook.” That was it.

HM: Whose idea was it to kiss a fish for the first time?

RH: Mine. I was very aware of some people who thought that fishing was cruel. There’s still people who want to ban fishing. I say, if you want to ban fishing, ban kids. Get rid of kids. I’ve seen kids get into fishing when they’re mischievous, and could have even got into trouble, who become responsible people teaching their own kids to fish. On that day that I said “yibbida yibbida”, I kissed the rainbow trout on the lips and put it back in the water. It launched my career internationally. It became my trademark. I believe it is a great gift to another angler by releasing a fish.

HM: Do you miss the TV?

RH: I miss the buzz of the red light going on the camera. But, Hame, fair dinkum, I got away with it for 15 years. I am happy to let it ride. Let’s not frighten the kiddies.

HM: Not many shows like that anymore.

RH: Because people are scared to produce like that now. It can’t be done now because people are scared to actually try things. They’re scared to make a mistake. The only person who doesn’t give two rats’ backsides about offending people or saying the correct thing is Sam Newman. You mark my words, people say they are sick of The Footy Show, but there will be hundreds of thousands of people tuned into The Footy Show when Eddie and Sam get back on. You know what they want? They want to be offended so they can complain. The world is full of people who just complain about things. A little bit of adversity goes a long way to getting ratings.

HM: The world is so politically correct now. If the environment was in 1989 as it is now, could you have gone to the heights that you reached then?

RH: I wouldn’t even get through the screen test.

HM: First unique player nickname you made up?

RH: I would think the uniqueness was with “The Garbologist”, who was our dear departed friend Paul Couch.

HM: Favourite nickname?

RH: Probably Sean Wellman. “Not a well-man”.

HM: What would you say to an aspiring broadcaster who was 20 years old and trying to get into the game?

RH: If you want to be popular, if you want to be technically correct, and if you want to describe the game perfectly, start looking for another job now. In two years, you’re going to need it. If you want to go on a ride, where every moment is just a joy: take a few risks, stretch the boundaries, dare to be different. Just be yourself and you might just end up all right in a very cut throat industry.

HM: Thanks, Rex.

RH: Thank you very much — lovely to see you, Hamish. Would you like another cuppa?