George Street’s long road from track to transport hub

The heart of Sydney has been fed by the same major artery for more than two centuries but this week all that changed.

Today in History

Don't miss out on the headlines from Today in History. Followed categories will be added to My News.

GEORGE St has been the artery keeping Sydney’s heart pumping since the early days of the colony.

This artery has now been closed off to bus and car traffic while it is transformed into a major light rail link running from Circular Quay to Randwick.

It remains to be seen whether the project, which has seen Sydney’s bus travellers thrown into confusion this week by dramatic route and timetable changes, will pump new lifeblood into Sydney’s centre or if like some past transformations it spells the end of an era. Either way it’s another huge change for the street that began life as a walking track.

When the British landed in 1788, pushing the Cadigal off their traditional lands, they discovered the indigenous people had already made well-worn paths around the area. One of these ran parallel with the trickle of fresh water, later known as the Tank Stream, that ran from a spring near what is today Hyde Park down to Sydney Cove.

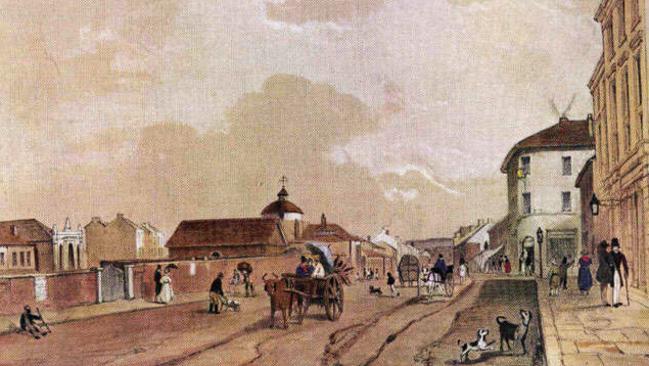

This track imposed a structure on the town that began to grow around Sydney Cove in the first few years, the soldiers’ barracks and convict dwellings stretched out in a line along the track, while to the east, across the river, was the Governor’s residence and the government domain. Consequently this street, at least part of which was known as Spring Row, became known as High Street, according to British naming conventions for the main thoroughfare.

By 1800 the street ran from a clay pit where clay was sourced from bricks at Brickfield Hill, past a burial ground, then rows of huts, the stocks and pillories, government stores to open out on to the market place that was then the centre of town.

It joined with Sergeant Major’s Row, a ragged street following the easiest path (again probably an indigenous track) through the lower part of the Rocks, running up to Dawe’s Battery, a small fort on Dawe’s Point.

This street saw the heaviest traffic on a daily basis and so when Lachlan Macquarie took over as governor in 1810 he ordered the street to be widened, straightened and generally improved to deal with the traffic and to create a thoroughfare more befitting the sophisticated centre of a colony. Macquarie also had the street joined to Sergeant Major’s Row and renamed it George Street after King George III.

Macquarie also moved the market south along George Street, commissioning a new building to house the markets. As the town continued to spread south along George Street Macquarie thought it prudent to build a brick wall around the burial ground, closing it off and establishing a new burial ground further south.

In 1811 a new road to Parramatta was opened that linked up with the southern end of George Street, which veered west after Brickfield Hill. This part of George Street, which became known as George Street West and later Broadway, led to toll gates which paid for the building and upkeep of Parramatta Road.

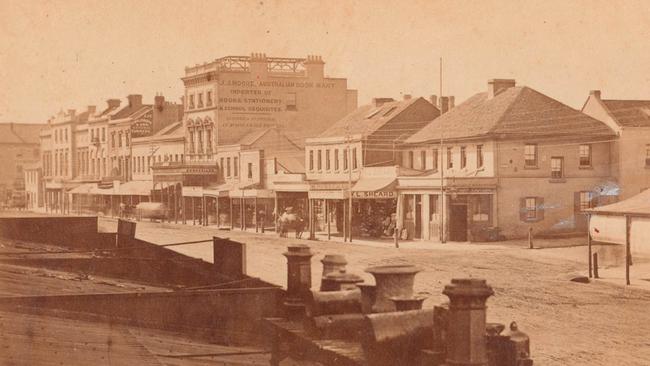

The 1820s saw the roads upgraded from dirt to beds of graded stone coated in ironstone. With less dust blowing around it made the street a more attractive shopping and business strip.

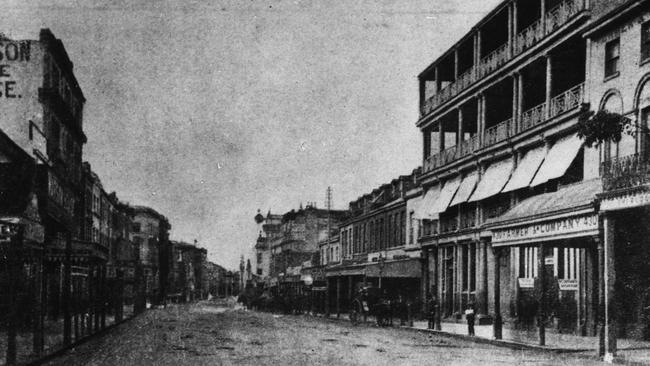

Paintings of George Street from the 1840s show rows of impressive three-storey buildings, some with attractive verandas, porticos and terraces. The street itself is a wide avenue, but is still largely a dirt surface rutted by cartwheels and horse traffic.

An 1855 map shows a branch of the street heading south that was then known as South George Street, meeting with Botany Road. After the opening of the railway in 1855, South George and Botany Road would become Lee Street and Regent Street.

The increase of traffic between Circular Quay and Central Railway, led to the introduction of horse-drawn trams in 1861 to help transport goods and people between ships and trains. Horse trams were upgraded to steam in 1879 and finally electricity from 1898.

But the traffic continued to increase, not helped by the introduction of cars. The stone-clad streets cracked and deteriorated under the strain, leading to experiments with sandstone bricks, woodblocks and later asphalt. By the 1920s asphalt had won out, but construction work on the road occasionally turns up woodblocks from the past.

CONSTANTLY CONSIDERING THE BEST WAY TO TRAVEL

BEFORE 1788 walking was the only way to get along the track that would later become George St.

Colonists introduced horses and convict-drawn carts.

Trams arrived in the 1860s along with the first motor cars in the 1890s.

Trams disappeared from George St in the 1960s, replaced by a fleet of buses.

A monorail served part of George St from 1988 to 2013.

More history: dailytelegraph.com.au/todayinhistory

Originally published as George Street’s long road from track to transport hub