From Tsars to journalists Russian politics has a long history of dealing with opposition in brutal fashion

NEMTSOV is not the first Russian politician to have ended up being silenced by dark forces in that country.

Today in History

Don't miss out on the headlines from Today in History. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Russia is a dangerous place to be a politician, particularly if you hold views opposed to those in power. Boris Nemtsov’s recent death at the hands of an unknown assassin is a case in point. Nemtsov had been due to lead a rally against war in the Ukraine on Sunday, but last Friday was shot dead as he crossed a bridge in Moscow, close to the Kremlin.

Nemtsov had recently expressed a fear that President Vladimir Putin would kill him, many people assume that is exactly what happened, although it has been officially denied and, perhaps ominously, Putin has vowed to take personal control of the investigation into the murder.

If people naturally look to the Russian leader with suspicion it is only because of Russia’s track record on political assassinations going back centuries.

Ivan the Terrible was notorious for simply eradicating any political opposition. He reigned from 1547 until his death in 1584, but remained suspicious of the elite aristocracy known as Boyars, working to curb their power and later finding ways to try them for treason and execute them. This was partly because he suspected the Boyars of poisoning his mother when she was regent.

When the monk Phillip II the metropolitan bishop of Moscow, from a Boyar family, publicly rebuked Ivan for his massacres of opponents and boyars he was arrested and later quietly strangled in prison by a member of the officers of his oprichnina, or inner court.

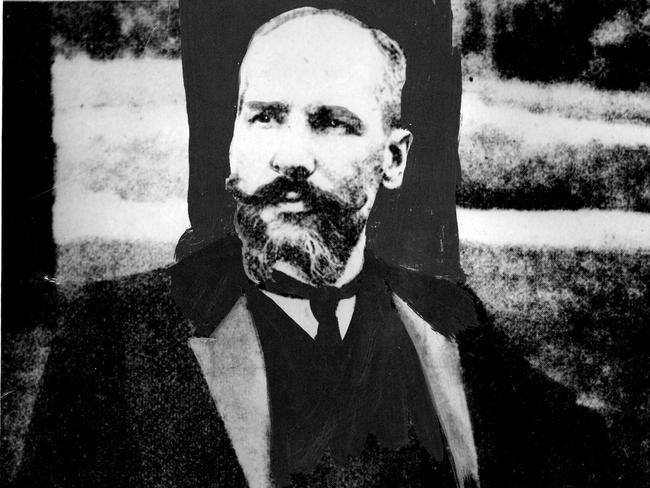

Prompted by the 1905 rebellion against his rule, in 1906 Tsar Nicholas II appointed Pyotr Stolypin as prime minister to bring about political reforms that would win back the peasantry. However, before his time as prime minister Stolypin had also been adept at repressing political opposition, which he did with ruthless efficiency during his time in office. He dismissed the left leaning Duma (parliament) and changed voting rules to elect more pro-Tsarist members, he also got busy hanging political opponents.

A political opponent dubbed the gallows “Stolypin’s necktie.” Stolypin challenged the man to a duel and quickly received an apology. However, Stolypin’s reforms in favour of the peasantry may have gone too far for Nicholas and opinion in the Tsar’s inner circle turned against the prime minister. The Tsar was contemplating firing his prime minister, but fate seemed to step in. While Stolypin was at the opera with the Tsar, the police guarding the opera house allowed an armed assassin to slip in and assassinate Stolypin. He died four days later from his wounds. The assassin was found to be a member of the Tsar’s Okhrana or secret police, who was also secretly a member of a leftist revolutionary party. He was hanged before he could be properly interviewed.

The result was that the government seemed to collapse into chaos as the Tsar took the political lead. He would be ousted during the 1917 revolutions and he was later murdered along with his family on government orders, for fear that he might become a beacon for opponents of the communist regime.

Communist leader Joseph Stalin would see some of the worst excesses in terms of removing political opponents. In the 1930s Sergei Kirov was building his own fiefdom as head of the Communist Party in Leningrad and his power was coming to rival that of Stalin. Publicly he acted the part of one of Stalin’s greatest supporters but secretly he was working independently of Stalin. In 1936 Kirov was assassinated by young party member Leonid Nikolayev.

The assassin was quickly caught and summarily executed along with other conspirators, eradicating evidence of Stalin’s hand in the murder. Stalin then used the assassination as an excuse to murder thousands of people alleged to be part of a conspiracy.

Year’s later Soviet leader Nikita Krushchev would hint that Stalin was behind the murder.

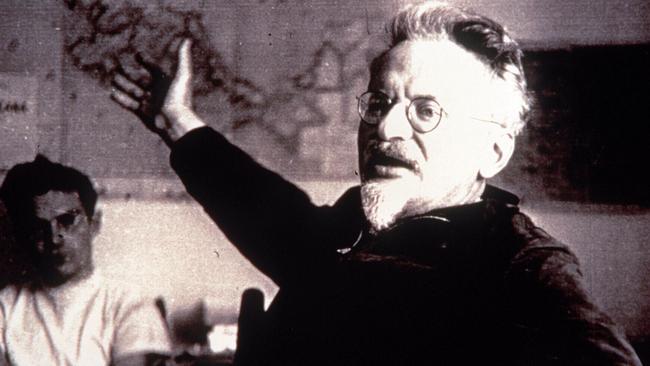

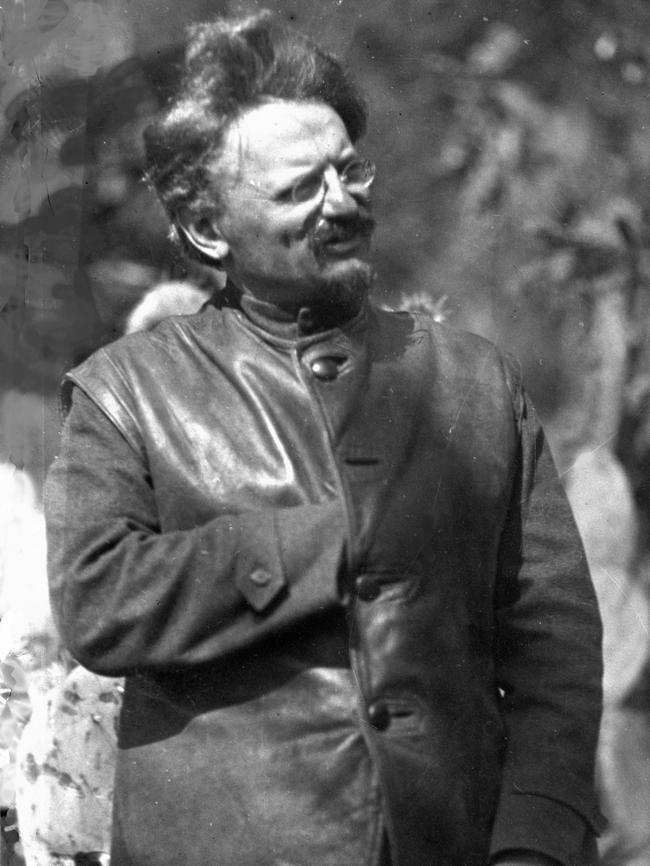

Stalin was also behind the assassination of exiled opposition leader Leon Trotsky. Trotsky was living in Mexico in 1940 when a young student Ramon Mercader wended his way into the exile’s inner circle and fatally wounded Trotsky with an ice pick. Mercader spent nearly 20 years in prison but was later given a hero’s welcome in Russia and the country’s highest decoration, Hero of the Soviet Union.

More recently Sergei Yushenkov, a noted Russian parliamentarian who fought for greater democracy, human rights and market reforms, was shot dead in 2003. Just hours before he had registered his Liberal Russia party. One of his election promises had been to investigate the 1999 Moscow apartment bombings blamed on terrorism but believed to be the work of government agents.

Originally published as From Tsars to journalists Russian politics has a long history of dealing with opposition in brutal fashion