Force was with George Lucas in scoring Star Wars merchandising coup

A new Star Wars film means a new range of toys, but the franchise did not invent the idea of selling merchandise to cinephiles

Today in History

Don't miss out on the headlines from Today in History. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Long queues and hype aside, one of the surest things about the release of a new Star Wars film is the flood of merchandise it generates.

Star Wars The Force Awakens opens on Thursday and stores around the world have already been flooded with merchandise ranging from toys to sheets, furniture, posters and other paraphernalia related to the film.

While the films do huge business in their own right, it has been the accompanying Star Wars merchandise that really made Star Wars creator George Lucas rich.

In 1973 when he was negotiating with 20th Century Fox to make the first film in the series he offered to drop his director’s salary from $500,000 to $150,000 on the proviso he retain merchandising and sequels. It was designed to help lower the budget but turned out to be a very astute move.

Assuming Lucas’ film would only have niche appeal, the studio agreed.

Defying these low expectations, the first film did huge box office business when it was released in 1977, making Lucas a fortune in toy sales alone. Many of the sequels were geared to selling even more paraphernalia.

While Lucas’ success inspired many other filmmakers to rethink merchandising rights and to tailor films to create merchandise, he was not the first to come up with the concept.

It is difficult to say who first had the brilliant idea of cashing in on the idea of offering the public souvenirs of their favourite movie. As early as 1915 there was a huge range of official Charlie Chaplin merchandise including dolls and wind-up toys, but these found it hard to compete with the knock-offs.

Another early merchandising push centred on the animated screen character Felix the Cat who first appeared on film in 1919. All manner of objects carried the Felix image including crockery, comic books, pins, and even a Felix the Cat wool-winding tool. The most popular was the Felix plush toy.

Similar merchandise accompanied Oswald Rabbit, a character created in 1927 by Ub Iwerks, who was working for Walt Disney, which was sold to Universal Pictures. Children could buy a stencil set and draw their own Oswald cartoons or chose between small Oswald figures and stuffed toys.

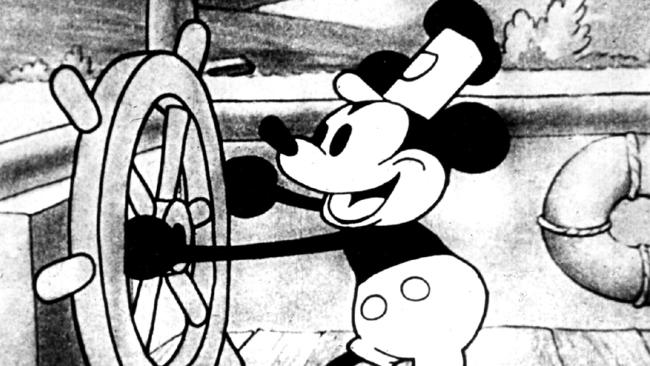

Because Universal owned the rights to Oswald, Disney got nothing from the merchandising. Then in 1928, after the success of the short film Steamboat Willie, Disney was approached by a representative from a company that manufactured school writing slates who paid Disney $300 to put Mickey Mouse’s image on the slates.

Disney knew he could use the money to help fund other projects, but it also inspired him to make Mickey the spearhead of what would become the Disney merchandising empire.

He hired Herman “Kay” Kamen to license and create the objects and soon Disney’s company was controlling a range of goods adorned with Mickey’s image. One of the most popular was the Mickey Mouse watch, launched in 1933, which helped revive the fortunes of Ingersoll-Waterbury watch company.

Each time new creatures were added to Disney’s animated menagerie, corresponding toys, games, jigsaw puzzles and even more practical items like cutlery would appear bearing images from the films.

When Disney moved into full-length feature films, beginning with Snow White in 1937, it expanded the merchandise possibilities.

One of the biggest selling items of the 1950s was a replica of the ’coonskin hat worn by Fess Parker in the Disney film Davy Crockett and in the Daniel Boone TV series. They were made of rabbit not raccoon and even Australian fans flocked to buy them.

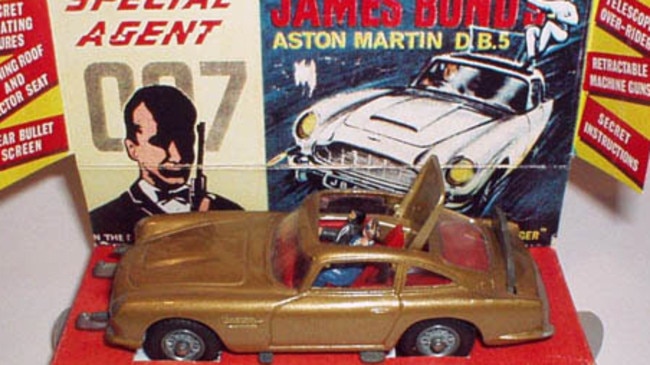

The Bond films, based on the works of Ian Fleming, spawned huge sales of Corgi’s toy Aston Martin cars. The films also inspired a 1965 slot car set that was fraught with mechanical problems but now sells for big money among collectors.

Fleming’s children’s story Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, about an inventor’s flying car, also kicked sales of toy cars when the film was released in 1968. A TV version of Batman spawned a big film version in 1966 with Batman merchandise including toy cars, games, Batman costumes and also action figures inspiring other comic book publishers to license action figures.

By the time Lucas created Star Wars there was already a market for toys based on film and TV subjects with an appeal to children and he had realised how lucrative it could be.

Originally published as Force was with George Lucas in scoring Star Wars merchandising coup