Files finally opened to reveal Gallipoli’s legacy of pain

A letter that arrived at the Australian Repatriation Department in February 1976 embodied a lifetime of unspoken sadness for one family of a World War I veteran.

Today in History

Don't miss out on the headlines from Today in History. Followed categories will be added to My News.

A LETTER that arrived at the Australian Repatriation Department in February 1976 embodied a lifetime of unspoken sadness.

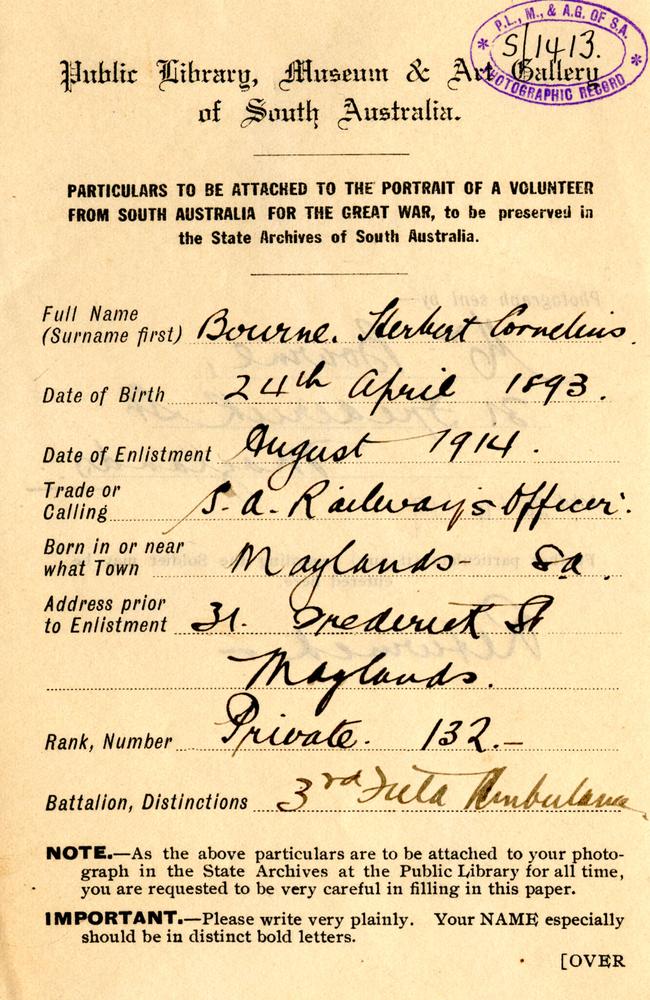

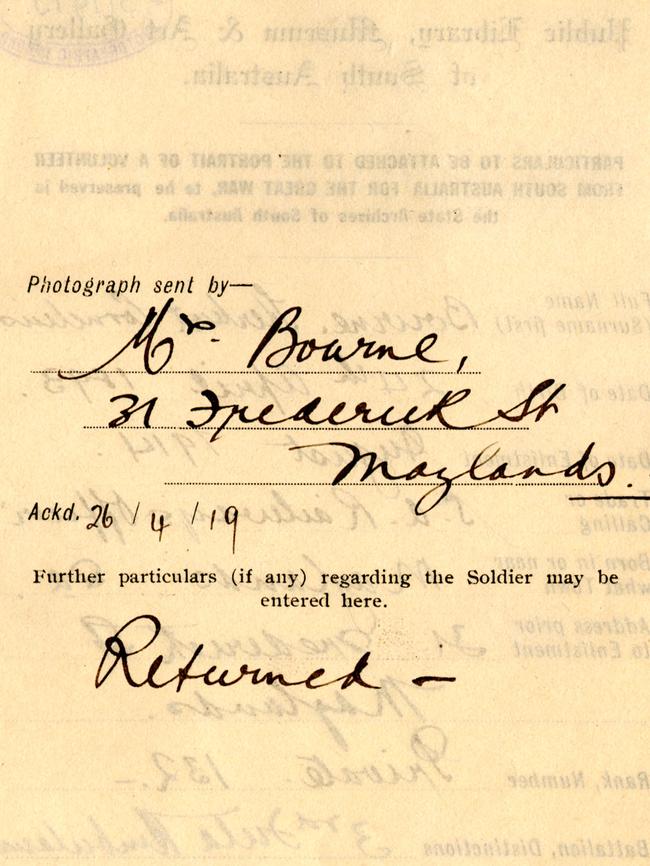

“Dear Sirs, I am wondering if you could assist me with confidential information regarding my father Herbert Cornelius Bourne,” it began.

The writer, Donald Bourne, was seeking clues about the origins of his late father’s temperament after serving in the Great War.

“Could you tell me the nature of my father’s sickness and cause of invalidity when he was returned home from Gallipoli?,” Donald Bourne wrote from his home in Norwood, Adelaide.

“As there are stories within the family of him being buried alive and other difficult war experiences, is it possible to know his field ambulance record and experience in the field of action? Having lived over 50 years with a dual personality problem, it would be of comfort to me and the family if there was ‘a war experience cause’ to his explosive temper and unpredictable personality changes.”

Several days later, deputy commissioner R.G. Collins wrote: “I wish to advise that it is not the policy of this Department to divulge any information held in departmental files.”

And that was that. Any chance to understand the mental and physical effects of Gallipoli was denied to the Bourne family, as it would have been to so many others.

Now the National Archives of Australia is commemorating the centenary of Anzac by opening its World War I Repatriation files.

Of its 600,000 repat files, the Archives aims to digitise 5000 this year. A further 150,000 files have been identified and described on the catalogue.

For the descendants of returned service personnel, the emotional significance of the $3.4 million project will be immense, says the Archives’ World War I curator Anne-Marie Conde.

Many of the files will reveal why a relative set off for war in normal health, and returned with debilitating mental conditions which were often misunderstood and neglected. Many returned people simply hid their mental anguish.

“The Bourne story stands for possibly many, many families who have had to cope with difficult, unusual, violent behaviour and have thought to themselves, ‘what happened to this man to make him the way he is?’ In this case, the family didn’t get the answers.”

Herbert Bourne’s repat files show he worked as a South Australian Railways clerk and apprentice jeweller and watchmaker, enlisting in August 1914 at the age of 21.

Bourne was in the first landing at Gallipoli on April 25, 1915 and served as a stretcher bearer with the 3rd Australian Field Ambulance.

“Stretcher-bearing was extremely dangerous and exhausting work, but Bourne endured almost the entire campaign until finally in December he was evacuated, having suffered for months from influenza and typhoid,” Conde says.

Bourne was often hospitalised for illnesses including influenza and “enteric”. He returned home in December 1917 and was discharged in April 1918 as “medically unfit (not due to misconduct)”.

“Bourne’s Repatriation files record in extensive detail that he had poor health for the rest of his life,” Conde says.

“He told his doctors that he was ‘blown up’ on Gallipoli, but this was not mentioned in his war records. Many veterans faced this dilemma. If an adequate record of a medical event was not kept and preserved at the time a veteran had little to back up claims about their post-war health.”

After the war, Bourne established himself as a jeweller in Moonta, South Australia. By 1951 he had moved back to Adelaide. But he suffered shortness of breath, fatigue and palpitations. One doctor believed Bourne’s symptoms were due to an “anxiety neurosis” concerning his heart.

Bourne was divorced in 1966 but preferred to say he was a widower.

In his final years, he was troubled by heart problems, diabetes, varicose veins and ulcers. These became gangrenous, and one leg was amputated in 1968. Visiting nurses described him as eccentric and lonely but resistant to joining a club.

In 1976 he told authorities he would feel like “a lost dog” without his married friends, the Banbrooks, who looked after him. He died that year, aged 83.

Access your relatives’ Repatriation files at

http://discoveringanzacs.naa.gov.au/after-the-war

Originally published as Files finally opened to reveal Gallipoli’s legacy of pain