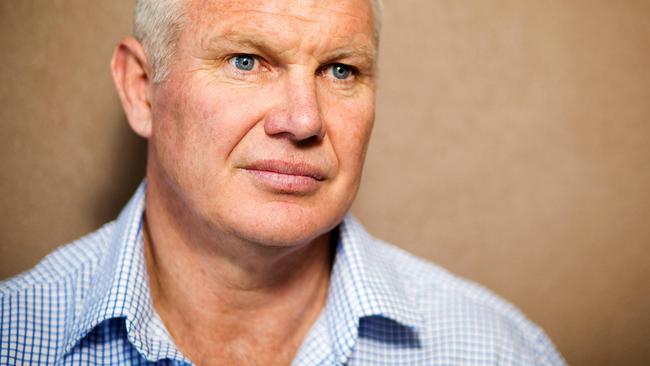

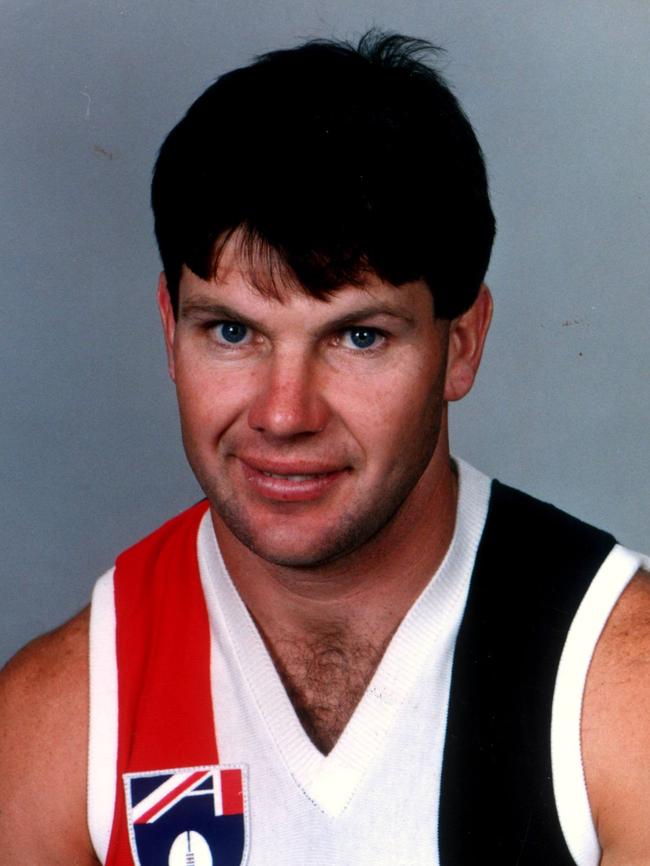

Hamish McLachlan interviews Danny Frawley: 'I completely fell apart'

On October 15 2017, Danny Frawley first revealed his battle with depression in an emotional interview with the Sunday Herald Sun. As Australia continues to mourn the beloved footy icon, we bring you that courageous conversation with Hamish McLachlan in full.

News

Don't miss out on the headlines from News . Followed categories will be added to My News.

The first time Danny Frawley spoke publicly about his battle with depression, the footy champion said he wanted to help people. As the footy world continues to remember 'Spud', we bring you his courageous Sunday Herald Sun interview with Hamish McLachlan from October 15, 2017

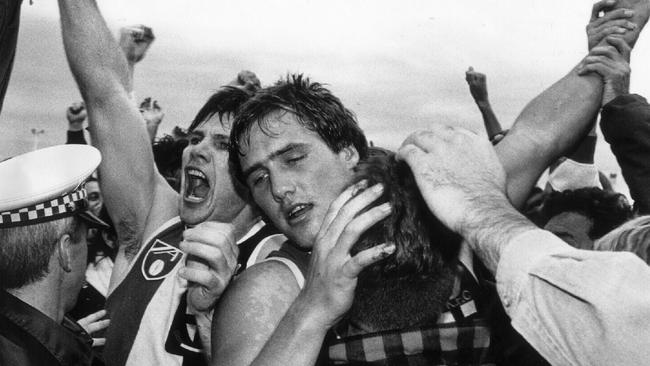

The Danny Frawley we see on our TV screens and hear on the radio is a fun-loving former St Kilda captain who doesn’t take himself too seriously.

Always up for a laugh, and happy to use himself as the punchline.

But when Danny was laughing on air, he was often grimacing off it.

We spoke about childhood, life on the land, loneliness, failing, dealing with depression and looking ahead.

Hamish McLachlan: Spud, you took a long time off work at the start of 2014. No TV, no radio — why was that?

Danny Frawley: I had a nervous breakdown, Hame. It was incredible and so hard to believe it was actually happening, but it was, and it did. I did a game for Triple M and I was losing a lot of sleep, and then I completely fell apart.

HM: Do you know why?

DF: There were a lot of issues, and unbeknown to me at that stage, a lot of deep seated ones. The tipping point for me came when I was CEO of the AFL Coaches Association, as well as playing this other character in the media.

HM: The happy-go-lucky guy?

DF: Yeah, that’s him. My role on air at Triple M and Fox was to throw people under the bus, and throw myself under the bus whenever required. But while I was doing that in the media, the Essendon supplement scenario was playing out. No one was prepared for it, no one could have been. I wasn’t ready for it. I was put in charge of the coaches’ association as more of a marketing-type person, and was trying to deal with a crisis that I wasn’t equipped to deal with.

HM: You really struggled to manage the coaches that were involved in the Essendon saga?

DF: Absolutely I did. The thing came out of nowhere and it put everyone on notice, no one more than me. I was dealing behind the scenes with a lot of the Essendon coaches, who were really struggling, and anxious as to how it would all play out. I got a lot of information that was confidential, and yet on the weekend I had to take one hat off, and put another one on for the media. I was really battling with it all. I started losing some sleep, and the more tired I became, the more I had to work. I started running a lot, trying to keep fit and hoping I would sleep, but I couldn’t, so I started drinking a lot, and then I started doing weight sessions, and in the space of three weeks without sleep, something had to give. I was waiting to get the cold, or the flu, or to become run down, but I just kept going. As my father used to say, “Work through it. You’ll be right, son”. So I tried to, and it all came to a head as a nervous breakdown.

I’M NOT EMBARRASSED ANYMORE

HM: You’ve never spoken about this?

DF: No, I haven’t. I’m not embarrassed by it anymore. I want to help people, and I just want to put it out there, as that’s what happened.

HM: So you had a nervous breakdown and in the end were diagnosed with clinical depression?

DF: That’s right. The most frightening thing happened when I was at the MCG one afternoon. I called Anita up after a game. I was sitting in the car park, behind the wheel. I had no idea where to go, or what to do. I was lost. I had to call my wife up to work out how to get home from the MCG. I’d been driving home from the MCG for 30 years, and I didn’t know if I should turn left or right!

HM: You didn’t know how to get home?

DF: I had no idea! It was an out-of-body experience. I was mentally shot.

HM: In what sense?

DF: I was confused and couldn’t find an answer. Any answers. How to get home isn’t one you should be searching for. I know that sounds bizarre. The only thing that I could think of was ringing Anita and saying “I’m confused”. I got home after she told me how to, and she said “You should take the dogs for a walk”. It was dusk in late April. When I got back I thought I’d lost one of the dogs; I wasn’t concentrating when I went walking. I got home, and basically sat down and just cried for two hours. I just thought: “This is not happening to me, what’s going on?”

HM: Did you think something was building in the lead-up to it?

DF: Looking back now, maybe I could sense there was, but I’d always woken up in the morning and be OK and just get on with the day and work it off. When you are a competitor, you just don’t want to let people know you’re hurting, even my family. Anita was the one that could see what was happening. I hadn’t slept for about three weeks, which is insane when you think about it. After the first couple of nights I should have been a bit more honest and forthright about it.

HM: Did you go and get help?

DF: I did. I went to our local doctor, where he asked me a few questions. He put me through a few questions and said “You’ve got a bit of depression”.

HM: Did that surprise you?

DF: Again, I was in denial. He said: “Look, here’s a few Temazepam. Go home, and you’ll sleep well”. I had the Temazepam, and slept for about five minutes. I rang him up again, and he put me onto a psychiatrist. This guy had a three-month waiting list, but happened to have a cancellation. I went in there, and that’s when I sat down and told him what was going on. He looked at me, with Anita, and said “You’ve had a nervous breakdown”. I didn’t know what that was. I just thought that was for people who had a bit of a weakness, or a bit of a brain malfunction, or for the mentally weak.

HM: Then you realised that was the furthest thing from the truth.

DF: I did. That’s a lot of the reason I want to talk to you today. I was the typical stoic farmer that always had the head up, the shoulders back, and it didn’t matter if your arm was chopped off, you just rolled the sleeve up on the other one and keep working through it. That’s the way I was treating this still, at that stage. I was in a bit of shock when he told me that. He gave me some Stilnox, and you’ve got to get that prescription for that, and I had that, and I only slept for about an hour.

HM: You can understand why sleep deprivation is a form of torture.

DF: Absolutely. I rang up the next morning and said, “Mate, I just need to sleep. I’m going off my head”. I was so tired, but my mind was just flying. He gave me two more Stillnox. He said “Look, that should put an elephant to sleep”. I had those, and they put me to sleep for two and a half to three hours. That went on for about three or four weeks, and I had to see him nearly every day for two to three weeks. I eventually called him one night and said: “Nup, I need to go somewhere. I don’t know what I’m going to do with myself”. At that stage all I wanted to do was get out of bed, walk around the corner and walk under a truck. That’s what I was thinking about.

I WAS OVERWHELMED

HM: That’s how bad your thoughts were?

DF: Yep, I was done, and I was thinking those things.

HM: What got you to this point?

DF: The tipping point was that I found myself trying to manage a position, with the Essendon saga, to which I didn’t have the skill set to manage. Dealing with the Essendon scenario was for people much better equipped than me.

HM: You were overwhelmed and highly stressed?

DF: I was overwhelmed, became highly anxious, mainly because I was underqualified. But I didn’t want people to know that. I thought to myself: “I’ve got to get through this Essendon scenario, and then I’ll resign, and then I’ll go into the media full time.”

HM: But you didn’t get that far?

DF: No, I didn’t. There was a review of the AFLCA, and rightly so, because the AFLCA had doubled in numbers in three years, from 80 to 160 coaches. The AFL were well aware of that. A couple of coaches wanted an independent review, so again, I felt a little bit precious because there was a board and staff who were all looking to me for leadership. In the back of my mind, I’m still thinking that as soon as I resign from the AFLCA, everything will be OK. I resigned about a week and a half after seeing the psychiatrist, and I still didn’t sleep a wink. I thought it would be a load off my mind, but it just wasn’t the case. Then he said: “Look, after the nervous breakdown, you’ve developed clinical depression.”

HM: What did you do to try and deal with it?

DF: I started reading books on depression, but it just wasn’t me, it wasn’t helping me. At the time I was working with Triple M and Fox Footy, and I told them I was feeling like I needed a break, so I intended to just take two weeks off. People started speculating and talking about me, and I really battled with that too. That’s why I get pretty upset with people when they start talking publicly about others when people are struggling. You’ve got to be very careful, because everyone’s different. I thought two weeks would be good for me. I’d stay off Triple M and TV, and I would get some sleep. But it didn’t help. It took me 18 months to actually come to the realisation that what was happening was a legacy of childhood and how I’d been put together.

HM: In what way?

DF: It started from a very young age. Being a farmer, I was always told to toughen up. There wasn’t a lot of compassion shown to me, no talking through things, just told to be tough, and get on with it. If I’d had a big night on the drink on the farm, Dad would get me up two hours earlier — “Work it off son” — or if I was feeling crook or needed to go to the doctor: “Don’t be moping around here”.

I HATED LOSING

HM: He sounds tough, but that’s how many dads were back then.

DF: He didn’t mean anything by it, it was the way it was. Farmers also work on their own, and are often isolated, they’ve just got to get the job done, and with little thanks or gratitude or recognition, but have to get it all done, regardless of the situation, in quick time, and get it done right. I battled a bit with that, too. And I think on top of that, it stemmed a bit from my older brothers. They were tough on me as older brothers were back then — but I think that had a pretty big effect too. I wanted to be like them and I developed into a tough competitor who hated losing and would cheat to win if I had to! And then school added to it. You went to your first day of college with 800 people and your head would get flushed down the toilet. For the year 12s, that was the thing to do to the new kids.

HM: How did this all lead to depression?

DF: In my mind, all of these things just turned me into this unbelievable competitor who was always struggling and trying to survive, and who had to win, and if I didn’t, I would feel like I’d failed. If I couldn’t find the solution or clean up the problem, I had failed, and I wasn’t worth anything. So when I failed with the Essendon stuff, trying to help the coaches, I think it was like a tipping point. It was the ultimate failure in my mind, and because I had let people down by not being able to save their jobs or make things easier for them, it was my fault.

HM: Always trying to win — even the things that you were no chance to win at?

DF: Yeah — the deep-seated issue was that I was a competitor, and the only person I was in competition against was myself, because I was never happy.

HM: It’s a big weight to carry — and a tough way to live.

DF: It is probably an unrealistic way to live, looking back on it, but that is how I was living, and that is a long time to be carrying all that self-imposed burden.

HM: You left the farm — you felt you had to?

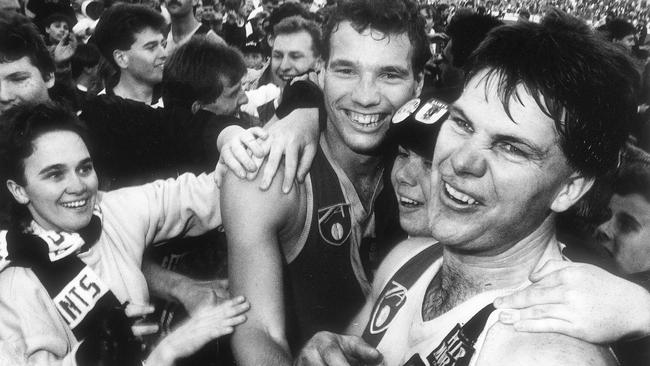

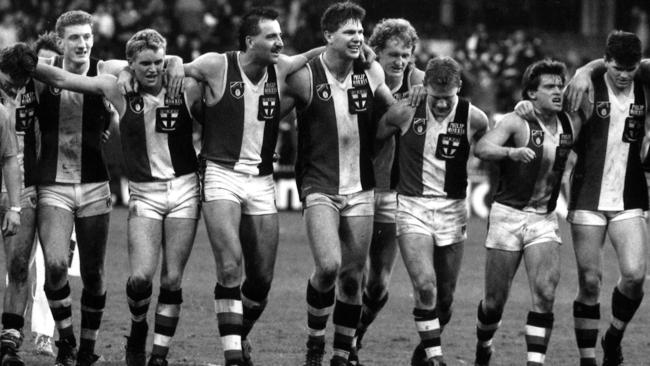

DF: I had to get off the farm because I didn’t really like the farm life. I found it very lonely. For the first two years I tried to get a game at St Kilda, but probably wasn’t working hard enough at it. Then I thought: “Sh*t, I’d better have a crack here or I’ll be gone”. I went off the drink, trained every night, ran with my brother who was a professional athlete, and got a job playing for St Kilda. That was the way out for me, the way to get off the farm. I liked the farm, but I didn’t love it.

HM: Did you feel you were failing on the far?

DF: I think so. I think when you are a competitor, you are never satisfied, which is dangerous. In my mind, the only thing I think I have succeeded with is my family. That was the one thing that got me through the last few years — that made me feel like I was able to achieve something significant and wasn’t a failure.

HM: Nothing more important than family.

DF: No, there’s not. My three daughters and my wife — they are my greatest achievement.

I WAS AN ISLAND

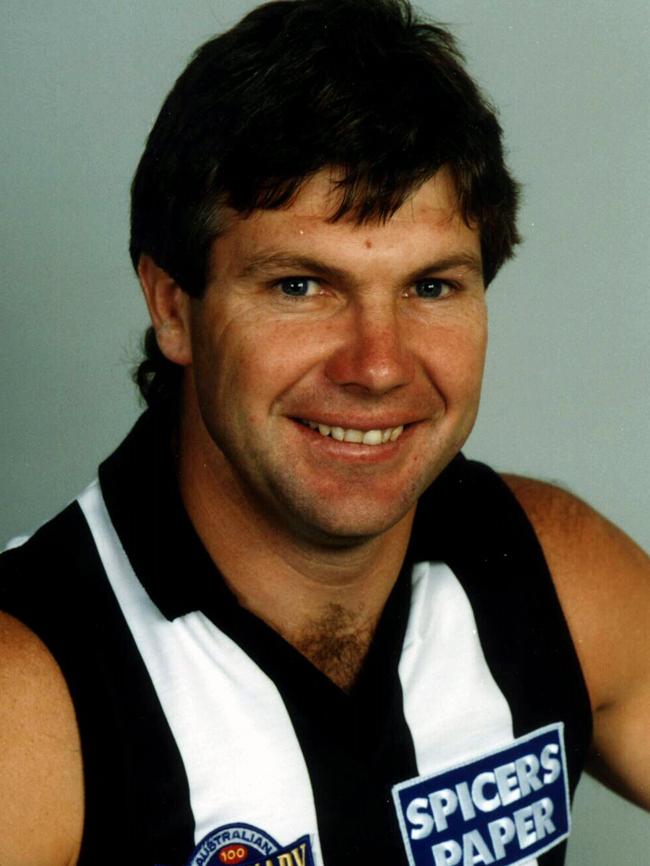

HM: They are magnificent. How did you battle mentally in the brutal world of coaching?

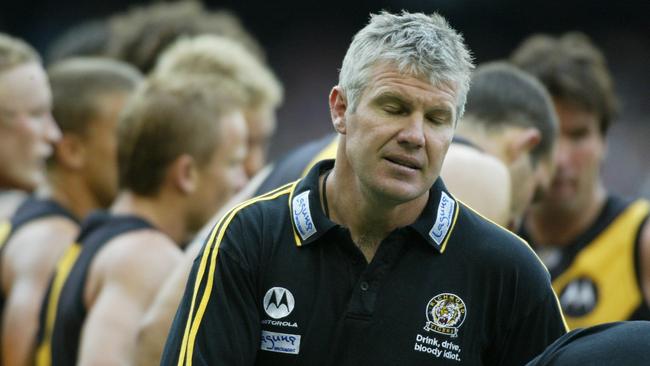

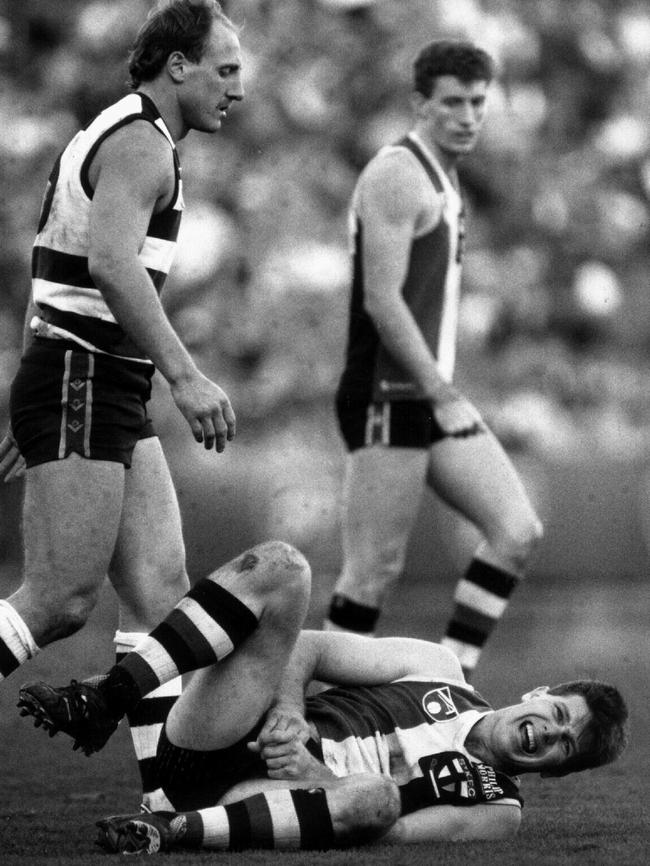

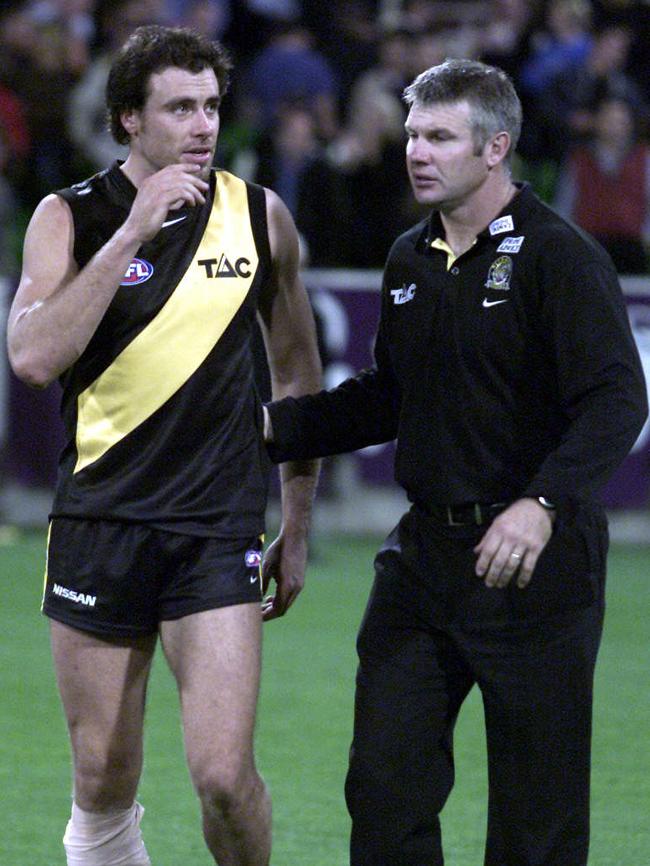

DF: When you don’t succeed — and it ends badly for most — you suffer mentally. When I retired from footballer, the competitor in me said instead of going back to the farm, I’ll go and ply my trade in coaching. My plan was to spend a couple of years at Collingwood, but North Melbourne were after me as well. I picked Collingwood because my uncle Des Tuddenham played for them. Tony Shaw was a young coach at the time, so I thought it’d be good. The plan was always to do two years, and then go back and help the late Trevor Barker to coach, because he was a really successful coach at Sandringham. At the age of 39 he died of bowel cancer, which again is a great story for people. Talk about a fitness fanatic. He just thought he’d had ulcers for a couple of months, and didn’t read the signs. That’s one of the great injustices, because he would’ve been a great coach. The plan was for me to go back and help Barks after a bit of experience with Collingwood. And then the great man died. I thought, what do I do now? I was on a bit of an island. I coached for another two years, and then the Richmond job came up. I thought, there it is. I’m ready to go. Collingwood were a great club, and they gave me a great opportunity. I was probably 1000 to 1 to get the job, but I interviewed quite well. It came down to two, and I got it. It was about me trying to achieve what was a little bit of a black hole as a player. I was going to coach a flag — the thing I didn’t achieve as a player. I had a little bit of success early, and then quite amazingly, I was 36 when I coached Richmond to the prelim.

HM: That’s bloody young.

DF: It was — but I was out of the game at 41, yet at the age of 54 now, in any other world sport I should be coaching in my prime! In 2001 we had a first-time coach in me, we had a first-time footy ops in Trevor Poole, we had a first-time CEO in Mark Brayshaw, and we had a first-time president in Clinton Casey. We wanted to win a flag. We were beaten quite comfortably by Brisbane in the prelim. At that stage I knew Brisbane were going to be a great team, but I didn’t know they were going to be the greatest team of all time. I thought the year was still a success. We’d come third, and as coach I had a win-loss record of around 61 per cent in my first two years. The great Leigh Matthews, one of the greatest coaches of all time, retired at around that percentage, so I thought I was the man! After a poor season in 2004 I resigned with nine games to go, and the easiest thing to do was to walk away. I should have, but I’d signed a deal with Richmond to coach to the end of 2004, and I thought being a man of my word, I’d do it.

HM: And just like that, a coaching career was over?

DF: I was waiting for the phone to ring after Richmond, and it never did. I was as low as shark shit, but I didn’t want anyone to know that.

HM: Embarrassed?

DF: A bit, and empty and lonely too. A week after I’d left Richmond, I could have had the going-away party in a telephone box and still had plenty of room! I had to sell my house because I thought I would be coaching ongoing and had bought a house with a bigger mortgage — but that’s fine; people have pressures. That didn’t worry me, because we bought a beautiful house around the corner.

HM: It can’t be healthy, coaching. Forget the departure, but the week-by-week analysis, criticism and critique of a coach is beyond almost any other profession.

DF: It is, and it’s interesting when I look back at my time. I was like that bloke from the Monty Python film with no arms and no legs …

HM: … just a flesh wound.

DF: Just a flesh wound, but I could still bite your kneecaps off. That was me. It really hit home for me on a Friday night, when we were beaten by 80 points. There was a young lad there that had too much to drink, and he actually spat on me.

HM: This was a spectator at the game?

DF: It was. It wasn’t a great night for the club, or me, or the players. The whole week was just bizarre. All of a sudden the Frawley name was put into disrepute. I heard my sister on the radio crying, saying “Danny’s a good fella”. We played Hawthorn on the Friday night seven days later, and a whole bus load of family and friends came down from Bungaree. I lost it. We won the game, but I walked into the footy ops afterwards and said: “I’m done. I don’t care whether we get in the finals; I’m done”.

HM: What was next?

DF: I left Richmond and got into the media and went to Triple M. All of a sudden James Brayshaw, as he does, pumps me up as a St Kilda champion, a St Kilda legend, and coach of a prelim side at Richmond, and I started feeling a bit better. I didn’t become a peacock immediately, but I was on the way up again.

I BLAMED MY FATHER INITIALLY

HM: You were feeling better about yourself, doing the media things, and then took on the CEO role of the AFL Coaches Association?

DF: Yeah — then the AFLCA role came along, but the inability to do the role well in tough times was the tipping point for me. It all came to a head via the Essendon stuff. The only way forwards for me was to establish the root of the problem — which I think was my upbringing. I actually blamed my father initially, but he only knew what he knew, and didn’t do anything that his father hadn’t done to him — work hard, show no emotion, and pass it on down the line. Then I blamed my older brothers for turning me into a complete and utter lunatic, as in a lunatic competitor, through the tough sibling rivalry. I never wanted to be beaten, but being beaten by the Essendon thing did my head in. I was out of my depth and I couldn’t help the coaches at Essendon as it was all too complex. I spoke to the head coaches in March of 2014, and I broke down in front of them — I just thought I was a huge failure.

HM: Did the coaches know you were struggling? Was it obvious? Were you open with them?

DF: I think so — the signs were there that I was struggling mentally. I remember a couple of coaches called me the next day asking if I was OK. I’d say “Yeah, I’m fine mate, no worries”, but I wasn’t, I was done. I was done six months before I tipped over the edge, there’s no doubting that whatsoever.

HM: I looked up the definition of depression. “Feelings of severe despondency and dejection. Self-doubt creeps in, and that swiftly turns to depression. Melancholy, misery, sadness, unhappiness, sadness, sorrow, woe, gloom, gloominess, dejection”. Is that what you felt?

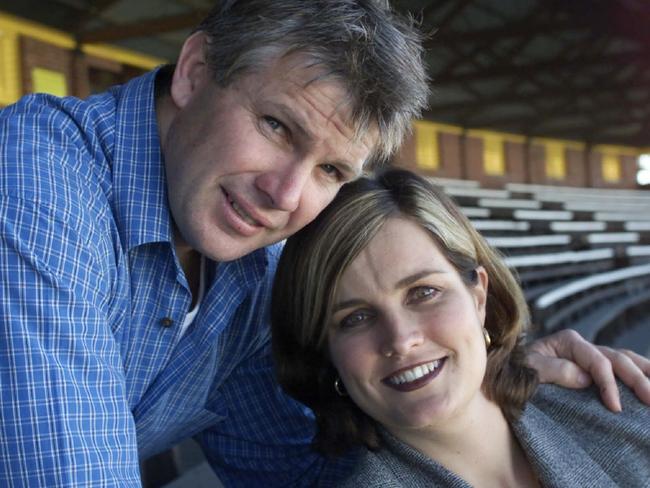

DF: Yeah, it’s all of that. The glass is always half-empty. That’s why I owe it to my beautiful wife, Anita. I remember she said to me: “You’re a great man and you have been a great husband, but you’ve turned into a bitter, twisted person that just looks at the negatives of everyone”. In a way, if I didn’t get depression, I would have lost my family too, as over the last few years I wasn’t a great husband or father. I’d made mistakes and unbeknown to me, I didn’t know that depression makes you selfish, and all I was doing was trying to chase happiness for myself at the cost of my family.

HM: Anita was very honest with you.

DF: She was, and she needed to be. She was hoping I’d get better, but felt she needed to tell me what it was doing to her and the kids, as it affects everyone around you too. I had to see a psychiatrist, and I’ll never forget when Anita had to drop me into a clinic in Melbourne. It was for people who were ready to do away with it all.

HM: End it all?

DF: Yeah. I went in there, and again, I couldn’t wait to get out of the place, but I’m so thankful that I went. It doesn’t pick or choose who it affects, and whoever it chooses, we all need help.

THE LITTLE BLACK HOLE GOT BIGGER

HM: It doesn’t discriminate.

DF: No, and all these guys in there knew me. I walked around the Tan with a few of them, and some of their stories were extraordinary. A lot of them were farmers, living on their own in debt during the drought. They kept looking at me saying “What? What have you got to be so disappointed about?” They were right, and I kept trying to convince myself that I had everything. A beautiful young family, no debt, a great job, but again, it took me 18 months. I went away to a farm, and I had a guy looking after me there. It was a farm where people were really struggling. I remember he said “We’re going to go for a walk”. We just went for a walk through this beautiful park, and unbeknown to me, every time he got on my shoulder, I’d just get two metres in front of him. Anita and the girls were telling me this for years. “Why don’t you just walk with us, Dad?” Again, it was just me being a competitor.

HM: You had to win the walk?

DF: I had to win. The guy goes: “Mate, you’re not smelling the roses, you’re giving them windburn. Slow down, what is wrong with you?” I was just like a hurricane for the first week up there. I had to get broken down to actually work out that it was me, no one else. It was just what evolved over a long period of time. The little black hole just got bigger and bigger. The thing that got me back was that I like to help charities. I’d go down to the Sacred Heart Mission on a Wednesday when I was battling, and I started coaching a lot of guys there that were living on the streets. It’s the best thing I ever did.

HM: It gave you perspective?

DF: It gave me a huge perspective, and it gave me an ability to tell them that I was battling. Some of their stories were remarkable. Kids were thrown out of home when they were 15! I’ve got a lot more empathy for people now, there’s no doubting that whatsoever.

HM: When you were at your lowest, you didn’t leave the house?

DF: I didn’t.

HM: You didn’t want to see people? You didn’t sleep?

DF: I didn’t sleep for three weeks! It got to the stage where I was running 15km going to work, to the AFLCA, before going and putting a footy jumper on to do a challenge with the chief (Jason Dunstall). Then I’d go back to work, put a suit on, get home, do some gym work, drink two bottles of red and lay awake all night with this huge noise in my head.

HM: You’d lay awake all night?

DF: All night.

HM: How many hours would you get. One?

DF: No. I never slept.

HM: At all?

DF: At all, for three weeks. I’ve done tests on it, and no wonder my brain shut down. I was waiting to get the flu or to become run down, but my mind and the adrenaline glands were just firing. The flood gates were open.

HM: Literally you’d lie and stare at the ceiling all night?

DF: All bloody night. I was doing meditation and things, and that’s why as I said, my brain got to a stage where I couldn’t get home from the MCG. I knew I was battling, but I thought it was just from a lack of sleep. Eventually I went to the doctor to get a couple of sleeping tablets, but looking back, it was always going to happen to me. That was just the tipping point. At the time when it happened I blamed Essendon, I blamed the media. Why couldn’t I have a job like JB? Why can’t I do this? Why aren’t I still coaching senior footy? Looking back now, I’m very thankful to wake up and realise the blame was all squarely on my shoulders, no one else. My life is all around my girls.

HM: Anita, Chelsea, Danielle and Keeley.

DF: That’s it. The rest is just a road map to get where you want to. As I said, they were there, but I wasn’t. I am now.

HM: All your focus was elsewhere at the time?

DF: It was. It took an illness for me to get perspective on life. I spoke to Schwatta (Wayne Schwass), and he was a great support. My three doctors were as well. I still see my psychiatrist.

HM: How often do you catch up?

DF: I see him every six weeks now, and it’s basically just a checklist to see how things are going. The big thing that I’ve found is that if something happens, or if I lost my job in the media tomorrow, I wouldn’t be worried. I’d be disappointed, but it doesn’t define me. My three girls do, and Anita …(begins crying). I’m sorry for getting a bit emotional.

HM: It’s perfectly normal.

DF: It’s just a part of life that happened, I guess. St Kilda knew I was battling, and they brought me back into their womb, so to speak. That helped, because it gave me a bit of discipline, and I was back to something that I loved doing. Coaching. I owe Richo and Matty Finnis a lot for giving me another opportunity, and to Fox and Triple M and SEN, all for different reasons.

ONLY WAY TO LEARN IS TO LISTEN

HM: Are you more attentive now as a husband and as a father than you’ve ever been?

DF: I listen more, I hope … I think. I’ve still got a bad habit of interjecting when I’m passionate about something. At the end of 2001 I lost a proportion between my lips and my ears. I didn’t listen. That’s what I do now: I listen. That’s how you gain wisdom. You don’t gain any wisdom if you’re talking 24/7. You’ve got that wisdom, but you’re not going to get any more, because all you’re espousing is what you know. The only way to learn is to listen. Listen and read. I love leadership, but the thing I say to young coaches when they become a senior coach is: “Don’t forget the ability to listen”. I reckon Dimma’s a good example of that. He’s got Balmey in, and I’m sure as the coach he listens a hell of a lot more. He’s in a happy place, the players are happy, and the club is happy. I think at times, when your ego gets out of control and you’ve got love bites in the mirror, you’re not going to listen. You’re hearing, but you’re not listening. I reckon I was like that.

HM: The treatment now for you — are you on any medication?

DF: I’m on antidepressants. Do I have to take them? Probably not. Do I take them as a matter of just keeping things in tow? Yeah. I do a bit of yoga. I do meditation.

HM: Does that help?

DF: It does. I do it with Anita. I’m in there with a lot of ladies, and they giggle a bit. I can’t touch my knees. let alone my toes! If someone had have told me four years ago I was going to do yoga, I would have said “You’ve got to be joking”.

HM: And if somebody had said you’d be wanting to do it!

DF: You’d think that can’t be a spud farmer from Bungaree! That was part of the issue. My persona was a senior coach, a tough gruff, a man who was a man’s man. Deep down I’m just a big, gentle puppy dog.

HM: I think probably a lot of men are, but they don’t feel like they can be who they really are.

DF: I owe my late father everything, but for him to cuddle one of his sons wasn’t an option. But that was the way it was back then.

IF YOU’VE GOT A WEAKNESS, BAD LUCK

HM: Did he ever tell you he loved you?

DF: Nup. But I knew he did, of course.

HM: Gave you a kiss?

DF: Never. But that was it. It was passed on for generations. We are now fourth-generation spud farmers in Australia, from Tipperary in Ireland. I’ve been back to Ireland, and it’s like looking at my father when I see those guys. It’s work all day, have a few beers every night, get up and do it again. If you’ve got a weakness, bad luck. If you’ve got an issue, grab a tissue.

HM: Not healthy physically, emotionally, or mentally?

DF: No. Most of my uncles on both sides of the family were farmers, and that’s why they died before the age of 60.

HM: On your darkest days, what was it that you felt?

DF: The darkest days for me were when I’d come to the realisation of how bad I was, and that I wasn’t going to get any better. There was no time frame as to when I would get better. And the “black dog” was barking louder and louder and louder. He’d go to sleep for a few days and I’d think, “How good’s this, he’s gone”, and then he would come back, and he would just bite you again and wouldn’t let you go.

HM: Are you better now at accepting that things will go against you and you’ll lose, and you don’t let it get you to a point where you feel like a failure?

DF: I am. If I’d have been a boxer, I probably wouldn’t have got as bad as I did, because as a boxer, there’s always someone better than you, and you get used to it. As a footballer you’re part of a team, and win lose or draw, you’ve still got your position. My position was great. Even though the team got beaten at times — and the Saints got beaten a hell of a lot — I’d still hang my hat on the fact that I beat Dunstall, or I beat Paul Salmon, or Warwick Capper. I don’t look back on being a competitor as being a weakness, and I’ve still got it there; you can’t fight being a competitor. I don’t cheat in Monopoly anymore with my daughters and my golf is getting better!

HM: Did you used to cheat?

DF: They’d go to the toilet and I’d grab another $2000 out of the bank!

HM: Because you had to beat them?

DF: I had to.

HM: That’s a problem!

DF: (laughs) It’s a huge problem, especially when they knew it was happening!

HM: (laughs) Dad’s a cheat.

DF: When they’d see a hotel on Mayfair they’d say “How did that get there, Dad!” I’d just say “I don’t know; it just fell there”. I think they understand all that now. The cheating was a part of being a competitor as well. That was like hanging onto the jumper of a full-forward because he was too good.

HM: You spoke about how you were drinking too much. Schwatta said he drank basically to numb the pain. Is that what you were doing?

DF: Yeah, I did. My wife and kids would go away, and I’d watch a movie and have two bottles of red. I thought it was good because my brain would just relax a bit. It was just not on, especially with the medication. I thought it’d actually put me to sleep, but it actually made me worse. It hyped me up too much. I’ve put on a bit of weight now and I’ve got to lose a bit, but when I was crook I was like a stick.

HM: How many kilos did you lose?

DF: I reckon I lost about 25. Initially, the fitness thing made me feel really good, so I thought I’d train for 10 hours a day. My endorphins felt good, so I just kept training and training and training, and all of a sudden I’d be beating guys out on the bike who were 20. It was the competitor in me again. It felt good, but it wasn’t doing me any good. It just got my adrenaline glands opened up again. The word “balance” is an interesting one now for me. I hear people talking about it, but balance, now that I’ve been through it, is just about being happy, and being able to float throughout the day. To me, balance was about fitting as many things into my day as I could … and then some.

SMELL THE ROSES, DON’T GIVE THEM WINDBURN

HM: Are you living simpler days?

DF: I love being on my own now, which is amazing. I did hate it. I love people, too. A part of my persona is that I can create quite a good environment, whether it’s team orientated, or at a function, or whatever, around me. Now I like to switch off, go down to the Brighton Baths and just sit on the decking there and read a book.

HM: And you’d never do that historically?

DF: Never, ever, ever. If I told you I liked colouring in, would you believe me?

HM: No.

DF: I do. There’s these books now that you can buy, and I just colour in. A game of chess, even. A game of chess for me in the past would have lasted five minutes, because if I was getting beaten and I knew the guy had me, we’d just start again. Now, I can have a game of chess on the phone for six months, and it’s all about the next move. It’s a bit like what the guy said to me on the farm: “Smell the roses, don’t give them windburn”.

HM: So how did you get from a point where everything was rushed, where you tried to do too much and where you had to win everything, to a simple, easier life? What was the lightbulb moment, or transition?

DF: Basically, I had to reprogram the hard drive. I had to retrain myself, which is really difficult when you’re in your early 50s. When you think historically, the only person that likes change is a baby with a wet nappy! My father never changed, at all, until the day he died. I’m proud of that, but when I look at some of his bad habits I think that I was starting to go down that road as well. That takes a lot of work now, because I can slip back a bit. I see my psychiatrist as a mentor now, and I can openly talk about it. If I had told someone two years ago that I was seeing a psychiatrist, I would have become really down.

HM: Embarrassed?

DF: I would think people would assume I’ve got something wrong with me.

HM: When did you get to the point where you were happy to talk about it?

DF: Probably now.

HM: I’ve never heard you talk like this.

DF: No. As I said, I’ve got a real passion to help people, and I’ve got a real passion for country people. I know the Flying Doctors do a great job. Farmers traditionally had a lot of manual labour, but now machinery has taken away a lot of jobs for farmers.

HM: And mateship?

DF: And mateship. Now, the machine takes over. The farmer’s just sitting there all day on his own and he’s got no one to talk to. When the farmers do a job on themselves, there’s no coming back from it. They’ve got no one to help them, and no one to talk to. I only got through it with support, mainly from my wife; I wouldn’t be here now without it. I was thinking about getting out of bed and walking onto Beach Rd under a truck. The only thing that kept me going was knowing I couldn’t leave my wife and daughters with that. I look back now and wonder how I got that bad. My brain just shut down, and the thoughts were getting darker and darker. There was no light at the end of the tunnel for me.

I SAW IT AS A WEAKNESS, NOT AN ILLNESS

HM: The stigma is something that we need to remove, because the more you say you talked about it, the easier it became. There is a reluctance to talk about mental health issues.

DF: There is, and I was reluctant until now because I still saw it as a weakness, not an illness. It’s an illness.

HM: If you had a broken arm, you’d talk about it. If you had a cancer, you’d talk about it.

DF: That’s spot on. I wanted to get those things. I wanted to have a heart attack. I thought, “At least that’s going to pinpoint the problem”. There’s a heart attack every 12 minutes, and I thought, “Why can’t I be one of those?” I thought I was on that path physically. I thought people were as weak as piss if they had a mental illness. I’d say it to their face. Now I realise that poor bastard was looking for a bit of support and I just put fuel on the fire, because now I know that if people talk about those things and you speak to them like that, you can nearly tip them over the edge.

HM: Do you feel like talking about it helps you?

DF: Yeah, it does — there’s no doubting that.

HM: If you were helping those that are listening or reading, what would be your advice? What were the best learnings for you on how to attack it and address it?

DF: Don’t beat yourself up: it is what it is, and you are what you are. Be honest with yourself. If you’re struggling, tell people. Don’t be like me and look in the mirror, start crying, and then cover it up and walk out with a smile on your face. You’re just living a lie. I wouldn’t do anything differently, and I used to beat myself up over that. Don’t make excuses. It’s all I knew and that’s why I did it. Now, having been through it, and now that I’m wiser and older, I’d do things differently. If I was losing two nights’ sleep, I’d tell Anita look, I’m battling a bit.

HM: And talk.

DF: Talk. I think doctors are getting a hell of a lot better at it. A good friend of mine, Dr Rohan White, is a great advocate of it. My wife and our girls talk openly about any issue. I get embarrassed about it, and I’ve got to walk out. Anita and her friends have coffee three times a week. I’m sure they talk about me, as I’m sure Soph talks about you. The soothing is there, and the advice is there around the coffee table.

HM: Self-healing.

DF: Men are stoic. Men over 40 have an issue talking about it. If we’ve got an erectile dysfunction for example, it’s a part of life. Go to Chemist Warehouse and get a Viagra, mate! Go to the doctor and tell them you’re struggling.

HM: How long did it take for you when you were diagnosed to ring your best mate and say “I’ve got depression”?

DF: My best mate was good. He was a bit like me though — he found it very confusing. We both come from the bush, we’re first cousins, we’re best mates, and we tell each other everything. He was great, but he didn’t get it. He didn’t get it because he used to look up to me as bulletproof. You’re bulletproof, you’ve done this, you’ve done that, and you’ll get through it, you’ll be fine. His attitude was very positive, but he just couldn’t relate to it. He now knows how bad it was, because he saw me a couple of times in the hospital. He was quite shocked. I was too, but that actually gave him a bit more of a sense on how bad it was.

HM: The beauty out of all of this is that positives come out of it. You’ve got a plan. You’re keen to get men talking. How are you going to do it?

DF: We’re going to start a show here on SEN, or at least a podcast. I’ve helped Schwatta a little bit, and it’s going to be more proactive than reactive. That’s what I like to do. It’s going to be a conversation, like you’re having with me, on a Sunday morning on SEN. We’re going to get some experts in and just get the conversation started. The underlying factor will be that no man should ever walk alone. If you look over your fence and see your mate hasn’t picked up the paper for two days, go and knock on his bloody door and drag him out. A lot of friends of mine dragged me out of bed to go for a walk. It was the best thing that ever happened. Did I go back to bed after the walk? Yep, but I got through a day, which to me at that stage was a huge goal. Just to get through a day was a real bonus.

WE CARRY FAR TOO MUCH STRESS

HM: It can be as simple as saying “Are you OK?”

DF: For men, it’s just a case of getting the conversation started. Women do an outstanding job, with breast cancer and all those initiatives. More males die of a heart attack than any other disease in Australia, and it’s due to two things. Physically, whether that be your diet or your habits, and mentally, the stress. We are carriers of far too much stress, and that has an impact physically and mentally. That’s it in a nutshell. You still need some enjoyment in your life. Mine’s my three daughters now and spending time with Anita. Would I have loved a son? I’d be lying if I said no. Would I crave for a grandson? Yeah, that would be a good thing.

HM: You might have one soon.

DF: Yeah, hopefully. It’s been good today, Hame — thanks! I don’t like getting emotional still, as you can see … (wiping tears).

HM: But the reality is, as you’ve just preached, don’t be afraid to speak, don’t be afraid to cry, and don’t be afraid to get emotional.

DF: And don’t be afraid to give a guy a hug. I do that now. Not as a smartie pants, it’s just to show that I’m here for them.

HM: You said your old man was very tough. My old man was tough too, but my brothers and I have taken the initiative and every time we see him instead of giving him a handshake, we give him a kiss. I’ve got a little boy, and I kiss him every day.

DF: And so you bloody should. We are changing and we’re getting better, but we can get a hell of a lot better, there’s no doubting that. As I said, I’m blessed looking back now with the life I’ve had. Hopefully I’ve got a lot more to go. I’m excited about the next phase of our life, because our girls will be off our hands soon, and Anita and I will have a great life. Getting old doesn’t worry me; nothing worries me, actually, other than the health of my four girls and my mother. The rest is just a part of life.

HM: They love you, I love you — thanks for talking.

DF: Good on you, Hame. Give us a hug.

If you or someone you know needs help, contact LifeLine on 13 11 14.