Computer nerds’ rush job would change the world

There was nothing basic about the fevered code-writing that led to the registration of Micro-Soft in Albequrque, New Mexico, 40 years ago.

Today in History

Don't miss out on the headlines from Today in History. Followed categories will be added to My News.

There was nothing basic about the fevered code-writing that led to the registration of Micro-Soft in Albuquerque, New Mexico, 40 years ago.

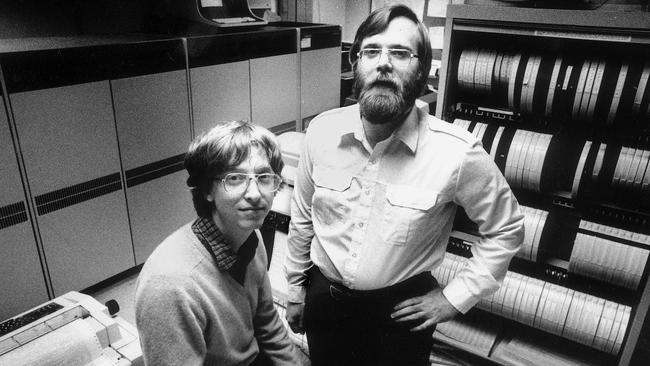

The start-up partnership, founded by Harvard student Bill Gates and Washington State University dropout Paul Allen to develop and sell BASIC software code for personal computers, was sealed on April 4, 1975.

Allen was 22 and Gates 19 when they took the first step towards realising their ambition to found a company which, “if really successful, could expand to employ 35 people”.

The two had known each other for seven years, since Gates enrolled at Lakeside School, a private boys’ school in Seattle. Both were regulars in the school’s innovative Teletype Room, experimenting with ticker-tape programs, then skipping athletics for code-time at C-Cubed, staffed by the University of Washington Academic Computing Centre.

Earning free computer time by attempting to find program bugs, they studied BASIC, FORTRAN, LISP and PDP-10 computer languages.

“Pretty quickly there were four of us who got more addicted, more involved, and understood it better than the others,” Gates recalled.

“They were myself, Paul Allen, who later founded Microsoft with me, Ric Weiland, who worked at Microsoft in the early days, and Kent Evans, my closest friend. He was killed in a mountain climbing accident when I was in 11th grade. So the four of us became the Lakeside Programming Group, the hard-core users.”

Allen had left high school with a perfect SAT score to study at Washington State University when Gates, still at Lakeside, was contacted by defence contractor TRW Inc, wanting to interview him for a job debugging software.

Gates called Allen, who joined him at the interview in Vancouver, British Columbia. When offered jobs paying $165 a week, Gates was granted leave of absence from Lakeside, while Allen dropped out of WSU.

The two also wrote class-scheduling software commissioned by Lakeside and launched their own company, Traf-O-Data, to analyse automobile traffic move-ments for local governments.

Gates applied and was accepted to Yale, Princeton and Harvard. He enrolled at Harvard to concentrate on pure maths, switching to applied maths when he found there were “several people who were quite a bit better than I was in math”.

By 1974 Allen was on his second university break in two years and still three semesters from graduation.

“I had a dead-end job at Honeywell, a crummy apartment, and a 64 Chrysler New Yorker that was burning oil. Unless something came along by summer I’d be going back to finish my degree,” he wrote in his biography, Idea Man.

Based in Boston, Allen was on his way to see Gates in December, 1974, when he spotted an edition of Popular Electronics magazine in Harvard Square. The cover story headline trumpeted “Project Breakthrough! World’s first minicomputer kit to rival commercial models”.

The Altair 8800, a computer based on Intel’s 8080 microprocessor, was developed by Bill Yates for entrepreneurial former airforce engineer Ed Roberts at his small electronics company, Micro Instrumentation Telemetry Systems, in Albuquerque, New Mexico. The first Altair 8800 machine could only be programmed to make its lights blink, and had 256 bytes of RAM with standard binary switches and LEDs on the front panel.

Convinced the Altair proved a commercial future in creating software for personal computers, Gates and Allen contacted Roberts to tell him they were developing an interpreter, or program code, although it did not exist. Their pitch followed engineering-industry practice of a trial balloon, an announcement of a non-existent product to gauge interest. Roberts agreed to meet for a demonstration in March, 1975.

Allen had written an Intel 8008 emulator for Traf-O-Data, which he adapted to the Altair programmer guide and tested on Harvard’s PDP-10, displeasing Harvard officials when they found out.

Allen and Gates worked for a month, buying computer time to complete their BASIC program on a simulated Altair, and hired Harvard student Monte Davidoff to write arithmetical routines. When Allen arrived in Albuquerque to meet Roberts, their interpreter worked perfectly.

When MITS agreed to market and distribute the Altair BASIC, Allen and Gates officially established their software licensing business, with Gates leaving Harvard to become chief executive. Allen came up with the name Micro-Soft, a combination of the words microprocessor and software.

Originally published as Computer nerds’ rush job would change the world