Citizenship’s benefits can always be weapons too

A bill allowing people to be stripped of their citizenship for terrorist activities has been introduced to Federal Parliament but citizenship has ancient roots

Today in History

Don't miss out on the headlines from Today in History. Followed categories will be added to My News.

In 1863 when America was torn apart by the Civil War, author Edward Everett Hale published a short story titled The Man Without A Country. The story is about a brash officer, Lt Philip Nolan, accused of treason, who shouts at his trial “I wish I may never hear of the United States again”. The judge then sentences him to live aboard US navy ships for life, never allowed to return to the US or to hear any news of his homeland. Nolan spends the rest of his days an outcast on the ocean, no longer a US citizen.

Hale was warning people, especially the secessionist southern states no longer citizens of the Union, that citizenship was precious. It gives access to a nation’s benefits, along with its protection, but in return duties must be performed, taxes paid and rules obeyed.

A controversial bill has been introduced in Federal Parliament that if passed would allow the government to strip Australian citizenship from dual citizens who have engaged in terrorist acts.

Australian citizenship has really only been recognised since 1949 when the Nationality And Citizenship Act came into effect, but citizenship more generally can be traced to ancient times.

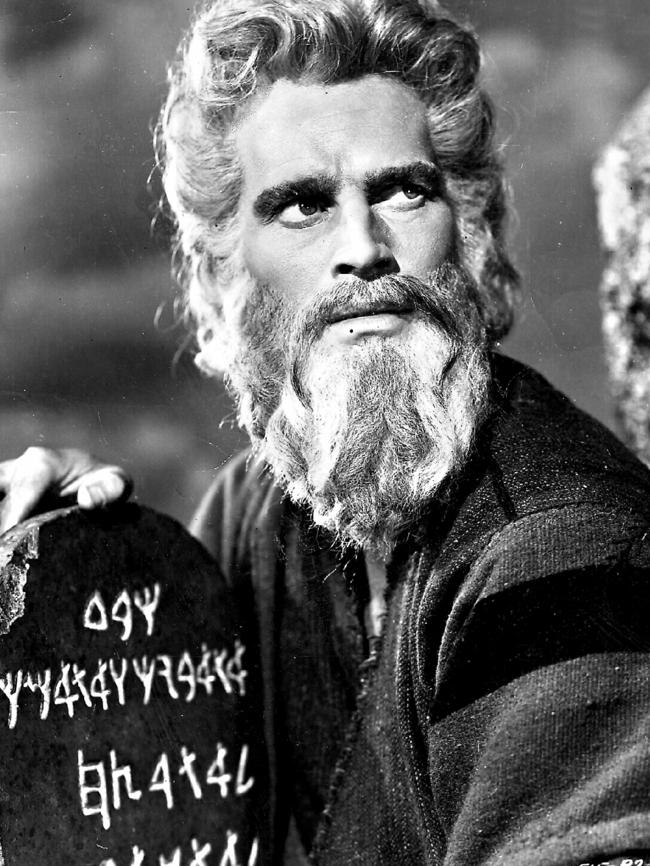

According to legend, the Ten Commandments delivered by Moses to the Jews who had escaped Egypt was an early document defining the rights and duties of the people and in return offering them the protection of the God who looked after their fledgling nation.

In Ancient Greek city states citizenship was well defined. Citizens, or polites, of Athens, for instance, were allowed a say in government and had the military protection of the state against other Greek city states. In return citizens had to take an interest in the affairs of state and provide support for the military, usually by serving as a soldier. However, full citizenship was limited to adult males. Women and slaves were not considered citizens. While technically citizens, the landless poor generally had neither time nor money to take an active part in politics. However an attempt by Athenian politician Phormiosis in 403BC to limit citizenship to property owners was soundly defeated.

Any citizens threatening the stability of the state could be ostracised, effectively losing their citizenship for a term of 10 years. In Sparta citizenship could be revoked from those who failed to pay a tax that went to pay for food for army training or if a citizen refused military service.

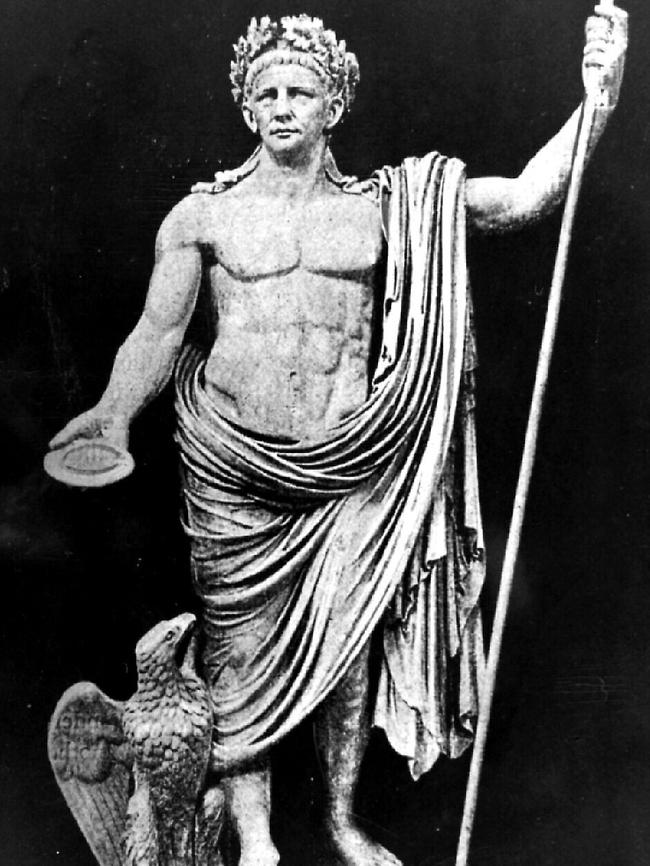

For the ancient Romans citizenship was first limited to people who lived in the city of Rome, but as the empire expanded Romans extended the privilege to people of conquered nations as an incentive to contribute to the empire.

Among its many benefits Roman citizenship entitled people to collect a grain ration, vote in elections and gave them the protection of the Roman army and Roman law.

Among other duties, citizens had to give military service to the state and if they failed in their obligations, allegiance or obedience to Rome citizenship could be revoked and the person would often be forced into exile. Emperor Claudius once revoked a man’s citizenship because he didn’t know Latin.

In medieval times citizenship of larger nations became secondary to duties owed to, and protection granted by, feudal lords rather than countries. But by the 18th century, as the political map of the world altered and larger nations came into being, the rights and obligations of people within national boundaries were increasingly defined in national and international law.

At first citizenship tended to be defined by property qualifications or class, but as the result of upheavals such as the French Revolution in 1789, the protection of the state, its laws and the right to take part in the political process began to be an important part of citizenship.

French Revolutionaries referred to each other as “citoyen” (citizen). From the 19th to the 20th century full citizenship would be widely extended to women and the poor.

The Americans would be fairly strict on their rules for being a citizen and at times used citizenship as a weapon against agitators.

There are notable examples of people being stripped of their citizenship in the 20th century.

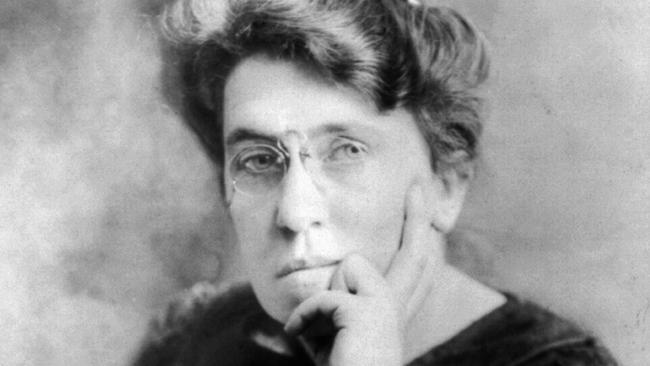

Anarchist Emma Goldman had emigrated to the US from Lithuania, then part of the Russian Empire, in 1885. But in 1908 she was charged under the Anarchist Exclusion act, which outlawed advocating revolution. Her citizenship was revoked and she was deported. Although she never returned to the US the government allowed her body to be brought home and buried in Chicago.

Aussie’s battle with the US

In the 1950s the US tried to revoke the American citizenship of Australian-born union leader Harry Bridges. Born in Melbourne in 1901, Bridges arrived in the US in 1920. In 1939 a government attempt to deport him failed because he was not affiliated with an international body advocating revolution. He was naturalised as an American in 1945 and later convicted of fraud and perjury, stripped of his citizenship and imprisoned. That decision was overturned in 1953 and his citizenship was restored.

Originally published as Citizenship’s benefits can always be weapons too