Can Olympic flame cool Korean conflict?

CROWDS at Sydney’s stadium roared approval when two Korean teams marched under the same flag at the 2000 Olympics.

Today in History

Don't miss out on the headlines from Today in History. Followed categories will be added to My News.

CROWDS at roads at Sydney’s Olympic Stadium roared approval when two Korean teams marched together under a blue-and-white flag at the opening of the 2000 Summer Games.

It was the first time the divided countries had united at an Olympic event since a single Korea competed at the 1948 London Games, before the Korean War began in 1950.

It is a well-worn cliche that sport and politics make uneasy bedfellows, although a contrary argument is that for 50 years, sport helped to keep the Cold War cold.

The first is certainly true of the fratricidal Korean conflict, and it is hoped the chill of a Winter Olympic competition in South Korea next month will cool overheated posturing in North Korea v. the rest of the world.

For the Koreas, it requires a warmer relationship, after both sides agreed to field a united women’s ice-hockey team when the Winter Olympics open at Pyeongchang, South Korea, on February 9. The two countries will also march at the opening ceremony behind a “unified Korea” flag showing an undivided Korean Peninsula.

Although welcomed in South Korea and the United Nations as a goodwill gesture by bombastic North Korean leader Kim Jong-un, members of South Korea’s ice-hockey squad now fear they will be dropped in favour of North Korean players in the six-aside competition. If the two Koreas do field a united squad, it will be the first unified team since 1991, when athletes from both nations competed at a youth soccer tournament and international table-tennis championship. The two Koreas also marched together in the 2004 Summer Olympics in Athens, and at the 2006 Asian Games.

North Korea’s Olympic competition began in 1964 when 13 athletes attended the Winter Games in Innsbruck, Austria, where Han Pil-Hwa won a silver medal in the women’s 3000m speed skating. The country made a strong showing at its first Summer Games in Munich in 1972, winning five medals, including a gold to Ri Ho-Jun in shooting. Ri Ho-Jun, then 25, was awarded the title of Merited Master of Sport of the USSR, the highest Soviet accolade for an athlete in socialist nations, and later became leader Kim Jong Il’s closest bodyguard.

While medallists can be rewarded with homes and cars, judo competitor Lee Chang Soo says less successful competitors were sent to work in remote coalmines. A former North Korean champion, Lee Chang-soo lost to a South Korean competitor at the 1990 Beijing Asian Games. He said his punishment was being sent to work in a coal mine, until he defected at a tournament in Spain in 1991.

Scientist Kim Hyeong-soo, who escaped in 2009, agreed that athletes who performed poorly faced the gulag: “If they had a gold medal, they would receive a huge benefit like a car, a new apartment in Pyongyang and extra rice. But if they have a bad result the athletes and the coach can be sent for hard labour for several months.”

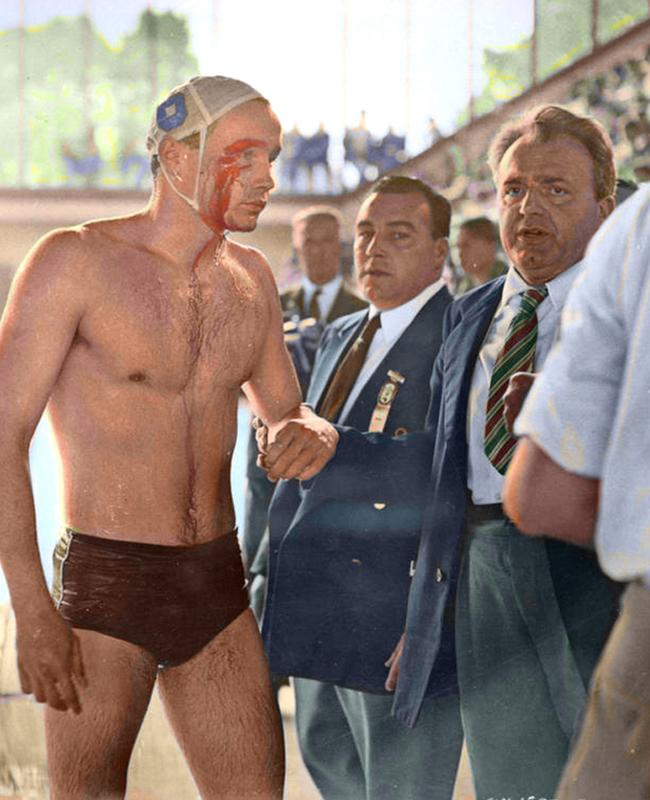

The Cold War delivered its own Olympic punishments, including the “Melbourne bloodbath”, when Hungary beat the Soviet Union in water polo at the 1956 Olympics. The game on December 6 came weeks after the 1956 Hungarian Revolution. As Hungary won 4-0, Hungarian player Ervin Zador emerged from the water in the game’s last two minutes with blood pouring from above his eye, after a punch from Soviet Valentin Prokopov.

And after two Olympic upsets, one against the US and another against the Soviets, two silver medals have never been inscribed. Americans had not lost an Olympic basketball game since it began in 1936 and say the 1972 Munich game is “the most controversial in international basketball history”. With the US and USSR tied at 49-49, with six minutes to go guard Doug Collins stole a Soviet pass at halfcourt. Fouled and knocked down by Russian Zurab Sakandelidze, Collins had two free throws and scored one, putting the US ahead 50-49. A Soviet at the scoring table shouted that a time out was called before the second free throw, but not granted. The last three seconds of the game were replayed, and Soviets took the lead to win 51-50. The US lost and refused to accept their silver medal.

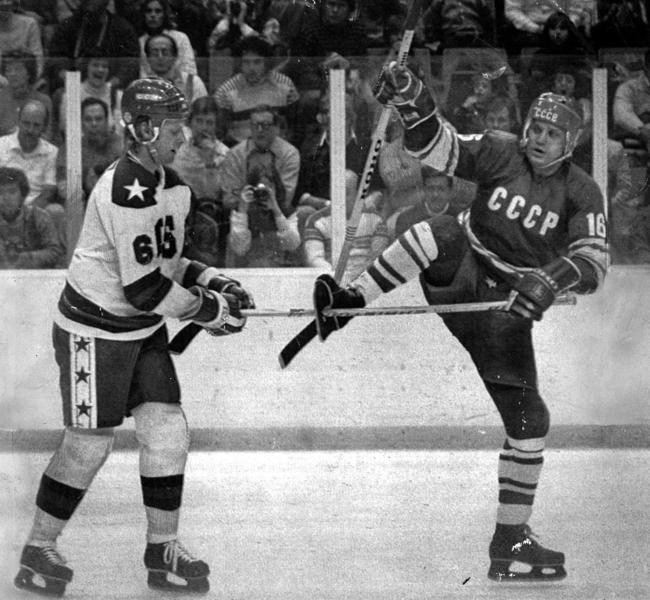

America retaliated at Lake Placid, New York, in 1980, when the US ice hockey team, comprising college players, defeated the Soviet’s four-time defending gold-medallists. The Soviet squad, considered the best in the world, lost 4-3 to the young Americans in front of 10,000 spectators. The Soviets later defeated Sweden to take the silver medal, while the Americans defeated Finland 4-2 to win gold. The Soviets had not lost an Olympic hockey game since 1968, and their team refused to have their names engraved on the silver medals.

Originally published as Can Olympic flame cool Korean conflict?