Bolsheviks formed Cheka, a secret police force to round up conspirators

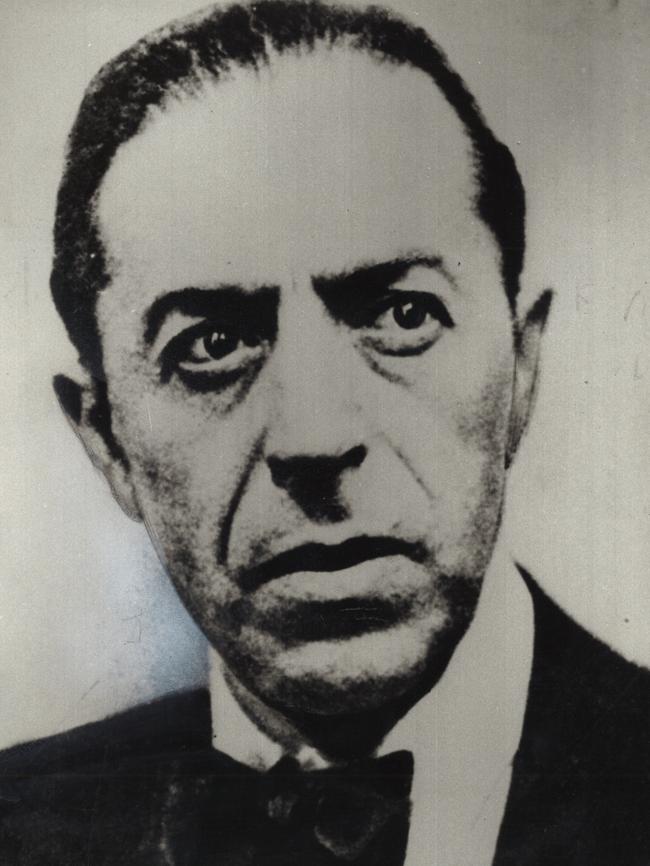

WHEN British intelligence operative Sidney Reilly tried to overthrow the Bolsheviks he didn’t count on their secret police being so effective.

Today in History

Don't miss out on the headlines from Today in History. Followed categories will be added to My News.

SINCE the Bolshevik revolution of 1917 Russian communists had been nervous about plots to oust their government. A century ago today they formed a secret police force, known as the Cheka, to deal with conspirators.

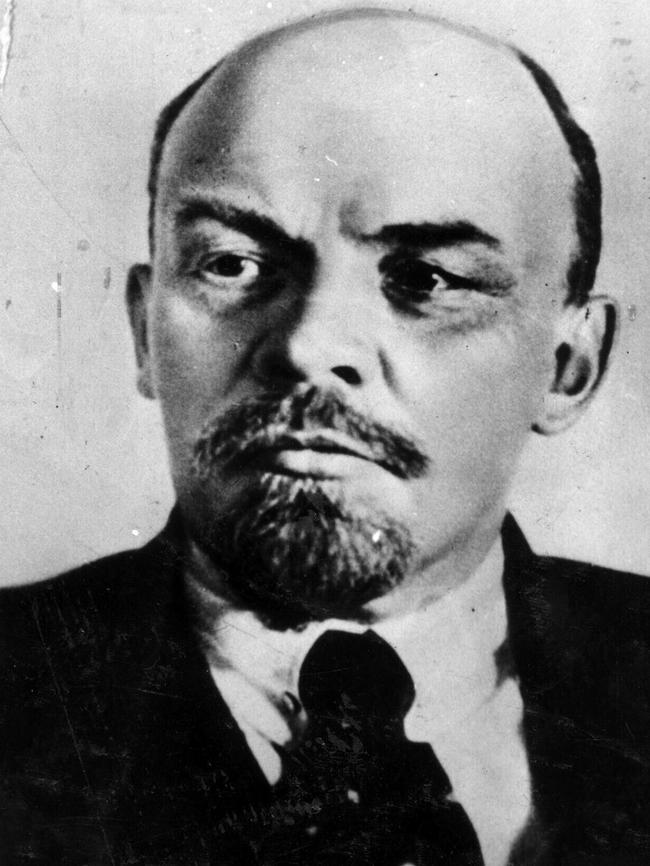

One early conspiracy was a British Secret Intelligence Service (SIS) plot to kill Russian leader Vladimir Lenin and stage a coup using disaffected elite Red Guard troops and counter-revolutionary organisations. But as SIS master spy Sidney Reilly was to set in motion his scheme in September 1918, another group of conspirators botched an assassination of Lenin on August 30.

The Cheka began rounding up suspects. They had been watching Reilly and correctly assumed he was up to something. The spy, cheekily dressed as a Cheka operative, fled Russia through Finland and Sweden before reaching London in November.

Although Reilly’s conspiracy was accidentally thwarted by the secret police, it provided the Cheka with a justification for existence, a chance to terrorise the population and entrench themselves as a part of the power structure. Even though the organisation would be disbanded in 1922 it was replaced by other organisations, such as the OGPU, NKVD and KGB, that all modelled themselves on the Cheka.

In the weeks after the Bolshevik Revolution on November 7, 1917, the fledgling government looked for ways to protect their fragile grip on power and combat counter-revolutionary activities.

Initially the Military Revolutionary Committee (MRC), established before the revolution, was given power to conduct searches, arrests and seizures, enforce curfews and protect alcohol stores. Lenin also authorised them to use the “strictest measures” to prevent profiteering, food hoarding and sabotage.

But the MRC was only ever meant to be a temporary body and was disbanded in early December. A committee headed by Felix Dzerzhinsky was convened to report on ways to fight counter-revolution and sabotage.

Dzerzhinsky, born in 1877 on the family estate in the Minsk region, was the son of a Polish nobleman. But Dzerzhinsky rebelled against his blue blood background and was expelled from school, just before graduation at the age of 18, for revolutionary activity.

He joined a Marxist party and was involved in organising strikes, but spent long stretches in prison in Poland, Lithuania and Russia. At the start of World War I he was transferred from a prison in Warsaw to Oryol Prison in Oryol 360km south-southwest of Moscow. When the Tsar was ousted in the revolution of February 1917, he was freed and later joined the Bolshevik Party, taking an active part in the MRC during communist revolution. He seemed a natural choice to investigate ways to ensure the security of the new government.

On December 20, 1917 he recommended the formation of “The All-Russian Extraordinary Commission for Combatting Counter-Revolution and Sabotage”. (The name Cheka was the acronym spelled out in Russian letters for the commission.) Its brief was to suppress “all attempts and acts of counter-revolution and sabotage throughout Russia, from whatever quarter” and to hand over conspirators for trial by a revolutionary tribunal.

The Cheka came into being on that same date, with Dzerzhinsky as its director. On December 29 the organisation was given the power to arrest suspects. By the end of February 1918 it was conducting summary trials and executions. Dzerzhinsky deliberately modelled his organisation on the Okhrana, the Tsar’s secret police.

Some complained that Dzerzhinsky was merely recreating the repression of the old imperial regime. He didn’t care, even setting up his Moscow headquarters in the same building of the Imperial Police.

As the country descended into civil war and plots against the government multiplied, the Cheka continued to grow. In July an uprising by the more moderate Left Socialist Revolutionaries (SR) was suppressed with the help of the Cheka and associated organisations.

When Reilly and fellow conspirator Robert Hamilton Lockhart, another SIS member serving as an unofficial ambassador in Moscow, plotted to overthrow the Bolsheviks they didn’t count on disgruntled SR member Fanny Kaplan shooting Lenin on August 30.

Lenin survived the assassination attempt but the shooting gave the Cheka an excuse to round up conspirators.

Reilly made it out of the country but in 1919 made another attempt to overthrow the communists which was even less successful. The Cheka was officially disbanded in 1922, but Dzerzhinsky then headed a new secret police force known as the State Political Administration (GPU) which later became the Joint State Political Administration (OGPU).

In 1925 members of the OGPU enticed Reilly to come to Russia to meet with an anti-communist group. He was caught and executed.

Dzerzhinsky died of a heart attack in 1926 but his organisation continued.

Originally published as Bolsheviks formed Cheka, a secret police force to round up conspirators