Andrew Rule: Doping scandal puts racing’s reputation down the tube

RULE breakers don’t record their activities, so the history of illicit treatments in horse racing is strictly word-of-mouth. That is until a series of text messages revealed one of the biggest scandals Australian racing has suffered, writes Andrew Rule.

News

Don't miss out on the headlines from News . Followed categories will be added to My News.

DANGLING a new Mercedes-Benz as bait for horse trainers was like tying a goat in the jungle to lure tigers: it was only a matter of time before the apex predators closed in for the kill.

For more than a decade, trainers from all over Australia came to the Warrnambool May races hoping to win a new car in a “long shot” bonus scheme for any trainer who could nail four wins over the three-day carnival, including one of the big feature races.

The four winners needed to bag the Mercedes could be from more than 20 races in three days, but one win had to be either the Grand Annual Steeplechase, the Warrnambool Cup, the Wangoom Handicap or the Galleywood Hurdle — races ordinary trainers might not win in a lifetime.

VICTORIAN RACING DOPING PROBE WIDENS ACROSS STATE BORDERS

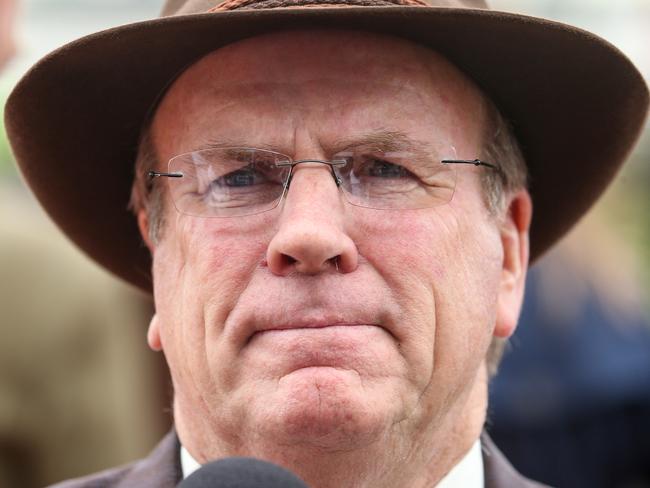

But Robert Smerdon was no ordinary trainer. He came from a family of horsemen with an uncanny knack of winning races when the money was on.

Smerdon had been around stables since he could walk, rode racehorses throughout his teens and was a professional jumping jockey while studying year 12 at St Patrick’s College in Ballarat. There are few shrewder heads in the business.

For the dozen years that Warrnambool offered a car as a prize, the club had been able to “hedge” against paying out by laying off with bookmakers, who happily took the bet for years. But that profitable arrangement started to unravel in 2010, when Smerdon arrived at the ’Bool with a string of horses, all tuned up and full of running.

The first day, the poker-faced Smerdon saddled the winner of the Brierly Steeplechase. Its name? Some Are Bent.

Next day, he snared the Mercedes with four more winners — the best of them in the Galleywood Hurdle, his second feature win of the week. That horse was Black And Bent, half-brother to Some Are Bent.

ACCUSED TARGETED BAND OF RUNNERS FOR ‘TOP UPS’ AT 2015 MELBOURNE CUP CARNIVAL

But if the horses’ names now seem grimly amusing, the headline in the local newspaper about Smerdon winning the car now seems a gem.

“Trainer’s key to success” it read, innocently referring to the keys of the $90,000 Mercedes he’d won. But, almost eight years later, that line has an irresistible double meaning in the middle of one of the biggest scandals Australian racing has suffered.

It began when stewards grabbed Smerdon’s right-hand man, Greg Nelligan, illicitly dosing a horse with sodium bicarbonate as the great Winx stepped on the track for the Turnbull Stakes at Flemington last October.

The timing of Smerdon’s extraordinary training feat at Warrnambool now looks interesting, even intriguing: thousands of captured text messages between members of the self-styled “circle of trust” (a handful of trainers, a stable hand and Nelligan and his wife) go back to that same year, 2010.

TEXT MESSAGES SHOW ACCUSED TRAINER’S GROWING AUDACITY

Among them is one exchange between the Nelligan and his wife, Denise, at the 2012 Warrnambool meeting, which shows the stable had its sights on another Benz.

“Well done to you,” Denise texted her husband at the races, apparently referring to a horse being illicitly dosed to win a race. “He needed it today. No one else is mentioning the car so the caller must have stuffed up.”

That year, Smerdon’s strike rate was again remarkable, but he didn’t quite win a second Mercedes. But after the rising star Darren Weir did in 2014 the bookies folded because they don’t like winners.

Smerdon and seven others charged under the rules of racing can’t be prejudged. But his contemporaries seem to believe they have seen the last of him at trackside: weeks ago, fellow Caulfield trainers who regard the dry, wisecracking Smerdon as a genius at his craft attended a dinner they dubbed “The Last Supper”. They doubt he will be rejoining them in the trainers hut.

His horses — including the brilliant young sprinter Nature Strip — have been scattered around other stables. He no longer needs to set an alarm for 3am.

It looks like the end of an era of alleged skulduggery. But when did it start?

NEW TEXTS SPARK FEARS RANDOM RACE-DOPING TESTS COMPROMISED

AS long as there have been horse races, there have been horse people trying to get an edge.

Speed and stamina stimulants range from the many opiate offshoots, such as oripavine and “elephant juice”, to bizarre exotics, such as “frog juice” and cobra venom, to heirloom “tonics” such as caffeine or arsenic, the one that killed Phar Lap. As for “stoppers”, there are many, though even a bucket of water slurped up by a thirsty horse close to race time is enough to nobble it.

Rule breakers don’t record their activities, so the history of sodium bicarbonate “milkshakes” and other illicit treatments comes strictly word-of-mouth. The word is that harness trainers used sodium bicarbonate “milkshakes” before it caught on with galloper trainers.

A pioneer of the “milkshake” in Victoria was the late Ron “Tubby” Peace, a colourful harness identity in a game that had plenty of scallywags and scoundrels.

The most efficient way to get sodium bicarbonate — the same baking soda used to make cakes rise — into a horse is to mix it with a palatable liquid and use a drenching tube and funnel. A skilled operator can thread the long tube through a horse’s nostril and down its throat into its stomach, avoiding the windpipe.

RACING CRUELTY CLAIMS: VICKS VAPORUB USED IN HORSE’S NOSE

“Tubby would cut a length of Nylex garden hose, rasp the end down smooth then slide it in,” recalls a current galloping trainer. More sophisticated operators would obtain veterinary-standard rubber or plastic tubes to do the pipe trick.

With the tube in place, the bicarbonate mixture is poured in using a funnel. This worked well until racing authorities banned all race-day treatments, which meant “tubing” went underground because the treatment is ineffective unless done shortly before the race.

The ban led to stewards following horse floats on race day, trying to catch handlers tubing horses just before they reached the track. Herald Sun crime reporter Mark Buttler once watched a trainer with tube and funnel get into his horse float at a service station near Geelong harness racing track.

The pacer won, at long odds, for the first time in many months.

Trainers anxious not to exceed a maximum “bicarb” level in pre-race tests worked out a quick way to “top up” secretly just before a race, using a paste squirted into the horse’s throat. This was what Nelligan was allegedly doing to Smerdon’s horse Lovani at Flemington last October.

If done close to a race, bicarbonate dilutes the lactic acid build-up in the horse’s muscles as it gallops. Like the illegal “blue magic”, “bicarb” is not a stimulant. It does not make a horse faster but slightly “braver”, allowing it to gallop a little harder at the end of a race than it otherwise would. It is natural and safe and, except on race day, an entirely legal feed supplement.

READ THE TEXTS: BRAZEN ALLEGED DOPING REVEALED

An experienced gallops trainer who admits he made good money punting on his horses back when he used “bicarb”, estimates that it boosts performance in “seven out of 10” horses and has no negative effects on the others. The improvement is just enough to make the difference between winning and losing a tight finish in a test of stamina.

There is no richer test of stamina in Australia than the Melbourne Cup. Which is interesting, apart from the current speculation over which horses were “topped up” before the 2015 Cup. Racing insiders say a trainer who broke into the big time by winning the Cup had earlier learned “milkshake” tubing from a seasoned Flemington trainer.

That trainer went on to extraordinary success in Group 1 races. His horses flew. By then, according to one impeccable source, the stable had learned how to combine “milkshakes” and something more sinister: EPO, the blood-altering compound that killed several Italian racing cyclists in the 1980s before its use was refined.

One of the stable’s most famous winners went from being a classy stayer to “a winged Pegasus”, says a contemporary trainer with hands-on knowledge.

LEO SCHLINK: TEXTS PAINT DISTURBING PICTURE

The Sunday Herald Sun published an expose of EPO doping during the 2012 spring carnival that upset both horse racing codes by alleging several trainers used the same drugs Lance Armstrong did to win a barely credible tally of Tour de France and other big cycling races. It named harness racing “legends” Bob and Vinnie Knight as EPO cheats, on evidence offered by a retired veterinary expert.

Since then, the cobalt scandal led to the charging of several trainers, including big names who were later acquitted.

Like the EPO family of drugs, cobalt chloride creates extra red cells so the blood carries more oxygen — an automatic boost to stamina. Horses treated with it run harder for longer and hit the line instead of hitting the wall.

For a while, cheats prosper. But nothing is a secret once more than two people know, let alone eight. If there is a falling out, there’s the risk one blows the whistle on the rest.

A former policeman with a lifetime in racing this week said he had dealt with painters and dockers, armed robbers and Mafia figures, but none were as “solid” as jockeys about not informing on each other. But it seems not all trainers are as tight-lipped as those who ride for them.

The exchange of thousands of incriminating texts astonishes one former jockey who knows the main players well.

It’s the law of the jungle. The tigers get the goat — but then they get shot.