WHEN Melbourne was awarded the rights to host the 1956 Olympics in 1949 it seemed like a blessing. But as difficulties began to mount it felt more like a curse.

The games were beset by problems including Australia’s tough quarantine laws threatening the equestrian events, as well as a shortage of housing for athletes and strikes delaying work on Olympic venues.

In 1955 International Olympic Committee President Avery Brundage visited Melbourne to check on the progress as he had been sceptical of the city’s ability to host the games.

Brundage was criticised for being autocratic, ruining careers, holding on to outmoded ideas and harbouring prejudices

On his tour of the venues he went to the Melbourne Cricket Ground, the main arena, and found only six workers on site due to an industrial dispute.

He chided Melbourne organisers: “It sets me wondering why Australia ‘knocks’ itself, when all other nations realise the potential boost they receive in the public’s eyes when granted the Games”.

He even threatened to take the event away from Melbourne and give it to another city.

The threat may not have been genuine, but it was enough to make Melbourne sort out their problems and, on November 22, 1956, the IOC president stood alongside Prince Phillip at the opening ceremony.

As the head of the Olympic movement Brundage was treated like royalty, but he was not well liked. While he did much to shape the modern games and make them successful, his time as an administrator was controversial.

He was criticised for being autocratic, ruining careers, holding on to outmoded ideas and harbouring prejudices.

Brundage was born in Detroit on September 28, 1887, the son of a stone mason. In 1901 he won an school essay competition; the prize was an all expenses paid trip to the second inauguration of President William McKinley.

He sold papers to help pay for his education, and was a keen sportsman, even making his own sporting equipment.

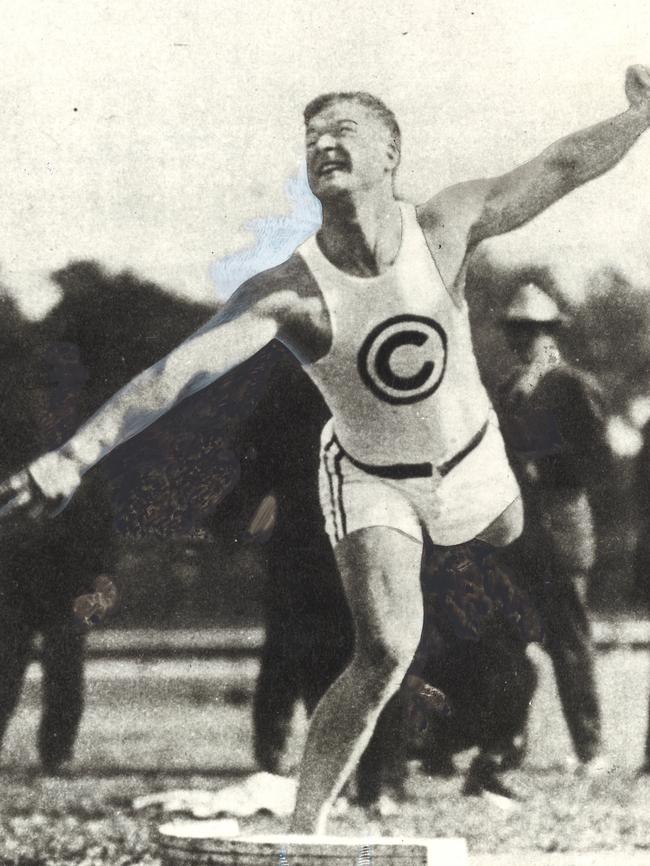

At the University of Illinois he studied civil engineering, graduating with honours in 1909, and also excelled at track and field.

He started working in construction for a major Chicago firm, but kept at his amateur sports. He joined the Chicago Athletic Association (CAA), finishing third in national championships for the “all-round”, a version of the decathlon.

He qualified for the Stockholm Olympics in 1912, finishing sixth in the pentathlon and 16th in the decathlon. He went on to be US all-round champion in 1914, 1916 and 1918.

In 1915 he founded his own construction company, using his sports profile to publicise it. When his dominance of all-round ended, he took up handball and was a top ranked player.

He also moved into sports administration, at first with the CAA but later with the American Olympic Association (AOA). In 1928 when General Douglas Macarthur resigned as AOA president, Brundage got the job.

The millionaire Brundage believed in the purity of Olympic amateurism, partly because of the corruption he had seen in the construction industry.

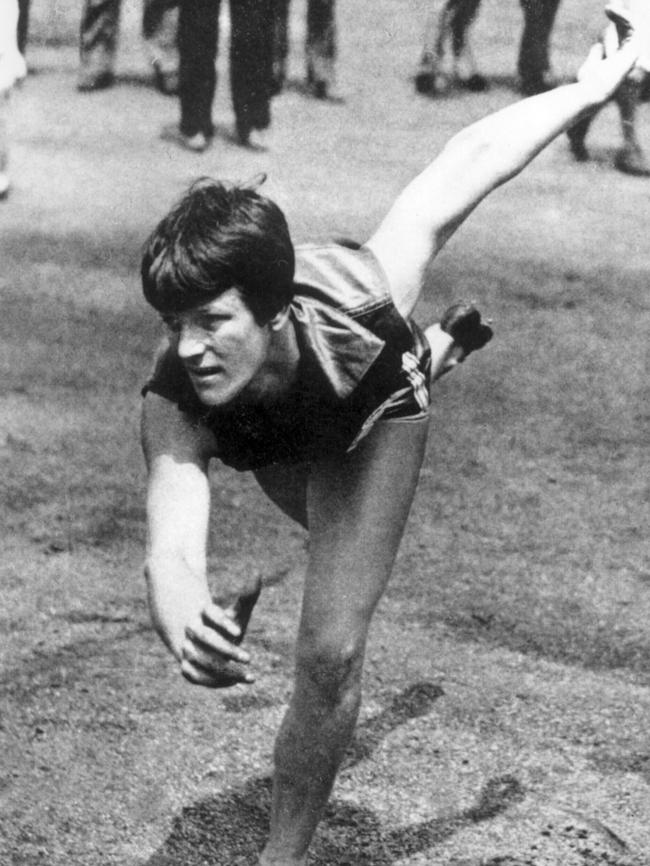

He rigidly enforced rules on amateurism. Among his victims, Los Angeles Olympics gold medallist Babe Didriksen who appeared in a car ad in 1932, was suspended for being a professional.

He commented: “The Ancient Greeks kept women out of their athletic games”.

When people debated boycotting the Nazi-run Olympics in 1936, Brundage, by then elected to the IOC, was initially concerned that some athletes, specifically Jews, were being excluded.

But after a visit to Germany he urged people not to boycott the games saying “the Olympic Games belong to the athletes and not to the politicians”. Brundage was accused of being a Nazi sympathiser.

When IOC president Henri Baillot-Latour died in 1942, Swede Sigfrid Edstrom become interim president and appointed Brundage vice president. In 1946 Edstrom was elected 4th president of the International Olympic Committee but resigned in 1952 and Brundage took over.

But he was soon mired in controversy. In 1953 he tried to bar ‘muscle women’ from the games saying, “ ... women simply aren’t built for rugged sports. Anyway, most of them look just plain silly”.

He also expressed doubts Melbourne could stage the games.

They proved him wrong, even saying “We have never had a better Games opening”.

The one down side had been the politics, particularly incidents such as the battle between the Russian and Hungarian water polo teams.

When the IOC was running low on funds in the ’60s he was slow to assure its future by negotiating television rights.

He said “The moment we handle money, even if we only distribute it, there will be trouble”, perhaps foreseeing corruption scandals that later beset the games.

The problem of politics despoiling the games continued to dog him. In Mexico in 1968 his demand that the US suspend two athletes over a Black Power salute was ignored.

In 1972 he was criticised for insisting the Munich games go on despite the kidnapping and killing of Israeli athletes by the Palestinians.

He resigned as IOC president in 1972 and died in 1975.

Gallipoli to D-Day: Aussie’s epic war story

George Dixon went ashore with the original Anzacs at Gallipoli, aged just 15 – and was shot. Three decades later he was fighting again, at history’s other most famous wartime landing.

Love story behind escape tragedy

An Australian murdered in the infamous wartime Great Escape died after swapping places with another man. And his story is still unfolding, 80 years on.