Albert Einstein changed the way we look at the universe, and life

The way scientists looked at the world changed fundamentally when a moustachioed scientist dropped his bombshell about the nature of gravity in 1915

Today in History

Don't miss out on the headlines from Today in History. Followed categories will be added to My News.

A century ago, while the world was at war, a group of scientists gathered at the Prussian Academy of Science to hear a lecture by an unassuming moustachioed man.

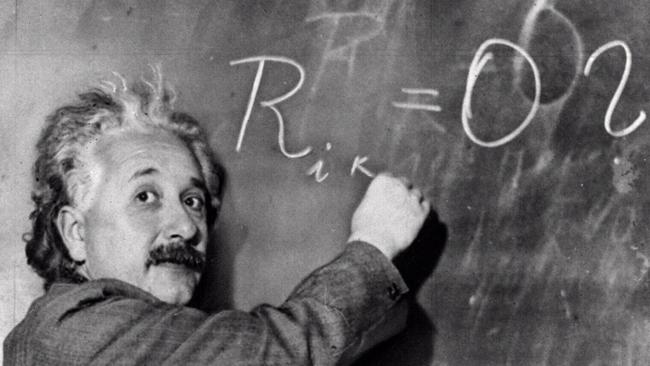

It would change the course of physics. On November 25, 1915, Albert Einstein unveiled his general theory of relativity, in which he theorised that gravity bent space and time. He was not an unknown.

Ten years earlier he had made an impact with his special theory of relativity, which said time and space were relative, that no object could exceed the speed of light and that the energy contained within any substance was equal to mass times the speed of light squared.

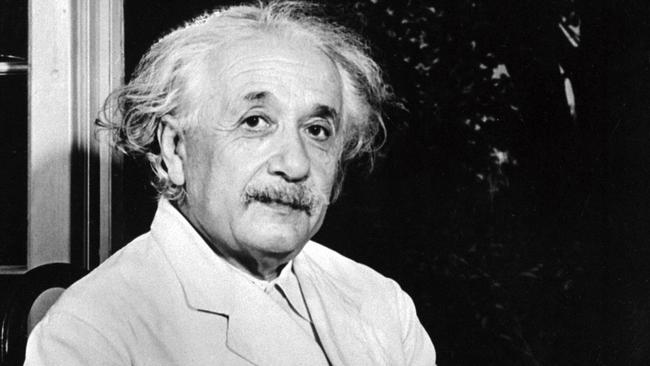

His earlier work had gained him influential supporters, such as German theoretical physicist Max Planck. But Planck and others remained sceptical after the 1915 lecture, until an experiment after the war confirmed some of Einstein’s theories. This changed Planck’s mind and hurtled Einstein to international fame.

The future genius had a difficult start. Born in Ulm in Germany in 1879, he was the son of a salesman and engineer. Einstein was three years old before he could speak and his education was interrupted by his father’s failed business ventures.

Yet he was inspired by his father and his uncle Jakob, who stimulated his love of maths, geometry and science. A family friend, medical student Max Talmud, gave him science magazines, one of which theorised what it would be like to travel with electricity through a wire.

This prompted the 16-year-old Einstein to wonder what would happen if you could race fast enough alongside a beam of light? He spent years trying to find an answer. To escape military service and to finish his high school education at a Swiss institution, he renounced his German citizenship in 1896 (he became Swiss in 1901) and went on to study at a prestigious Swiss polytechnical school, specialising in mathematics and physics.

When he graduated in 1900, he was far in advance of many of his professors, but his tendency toward independent research and learning made it hard for him to get recommendations for an academic position. He found low-paying jobs for a time but in 1903 got a job as clerk at the patents office, which at least was steady work and made use of his intellect.

It also gave him time to think on subjects that interested him, especially his questions about light.

His outpouring of genius in 1905 and the support of scientists such as Planck finally earned him a doctorate and entry into the academic world. He was appointed to a teaching position in 1908, became a full professor in 1911 and in 1913 was appointed head of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics (although the institute would not be properly set up until 1917), which allowed him to indulge purely in research. By then he was working on a solution to some of the problems with Newton’s theories on gravity, culminating in his landmark 1915 general theory of relativity.

In 1919 two ships set out on expeditions to different parts of the globe to observe a solar eclipse, which showed the light from stars was bent as the stars passed near the sun, as Einstein predicted. The results of the experiment were announced at the Royal Society in London and made headlines in The Times.

Einstein became famous, enhanced when he was awarded the Nobel prize for physics in 1922 and travelled the world on speaking tours.

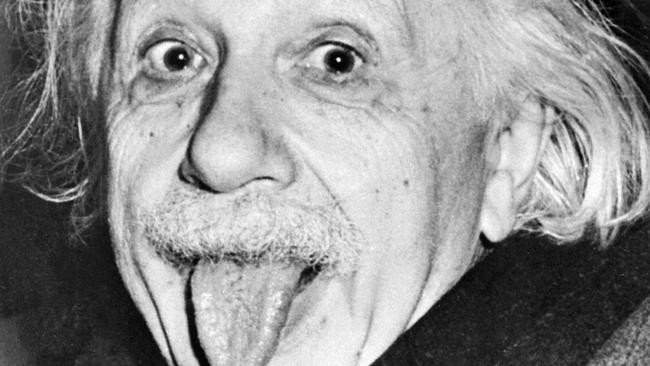

His theory was unfathomable to the general public but his image as a slight dishevelled and eccentric genius endeared him even so.

The rise of Nazism drove him out of Europe and he eventually settled in the US, where he became a citizen in 1940. In 1939 he and physicist Leo Szilard prompted the US president Franklin D. Roosevelt to begin developing an atomic bomb, for fear the Germans might develop one first.

To the end of his days he worked on a unified field theory that would bring together all the laws of physics and nature in one elegant theory.

He remained a popular figure. Snapped by paparazzi in 1951, he showed his annoyance by poking out his tongue. He liked the photo and it came to symbolise his informality. He died in 1955 of an aneurysm, without ever finishing his unified field theory.

Originally published as Albert Einstein changed the way we look at the universe, and life