Werribee Research Farm: The scientific ghost town where IVF was born

It was a place where scientists milked mice, 60 radioactive cows were buried and pigs were dissected for heart research. It was also the place where IVF began. Care to take a look inside?

Lifestyle

Don't miss out on the headlines from Lifestyle. Followed categories will be added to My News.

The surgery tables at the Werribee Research Farm are caked in a quarter-century worth of dust.

Stacks of filed say untouched in a muddied cupboard.

A clock ticks on the wall of a meeting room, where a whiteboard still has equations scribbled on it, as if scientists all just walked out one day.

Aside from a thriving beehive tucked neatly into the outer corner of an old animal pen, the place is lifeless.

But the scientific ghost town was once alive and bustling, with world-first finds and fields of vital agricultural resources.

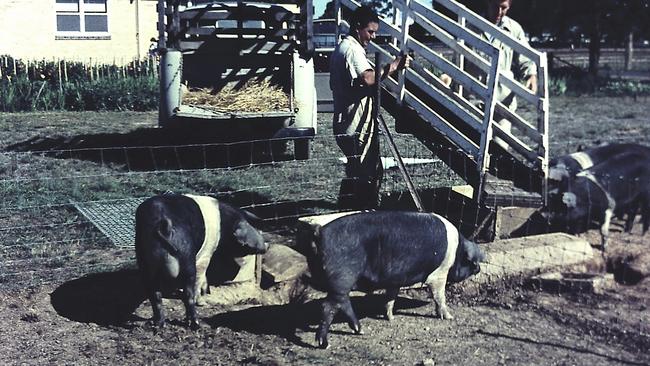

It was a place where mice were milked for cancer research, up to 60 radioactive cows were rumoured to have been buried and pigs were dissected for research on human heart surgery.

It was a place that produced vegetable seeds for local and international needs during World War Two, ergotine for shell shock and when morphine supplies began to dwindle, opium poppies were grown to fill the gap.

It was a place where more than 300 women were trained through the Women’s Land Army in farming practices and where cheesemakers from around the world gathered to learn the trade.

It was also a place where hundreds of scientists, farm workers and their families lived in cottages.

One of those scientists was emeritus professor and distinguished scientist, Alan Trounson, an early pioneer whose experiments changed the lives of millions of people worldwide.

Werribee: The birthplace of IVF

In 1968, at the age of 24, Alan Trounson began poking and prodding at what would

eventually grant millions of couples and singles across the world their greatest wish:

to have a child.

As a MSc student, Trounson was given the opportunity to live and work among other brilliant young scientists at the renowned State Research Farm in Werribee.

The farm, acquired by the Department of Agriculture in 1912 to battle the social troubles of the economic depression of the 1890s, had become a thriving science and agricultural hub.

Trounson, a rugby-loving farm boy from outback NSW, was housed alongside his peers in a row of motel-style rooms with shared bathrooms.

In 1971, the inquisitive young scientist was sampling blood from farm animals day and night to identify the difference between twin and single ovulating animals.

“You would collect blood from the sheep, every hour or every half-hour at different times, because you wanted to collect a peak of the hormone that was being released into the blood,” he explained.

It was then that Trounson met gynaecologist Carl Wood, who would later become known as the father of IVF.

Craving more knowledge, Trounson moved to Cambridge to study biochemistry and physiology, where Australia’s greatest scientific competitors were also probing the mystery of infertility.

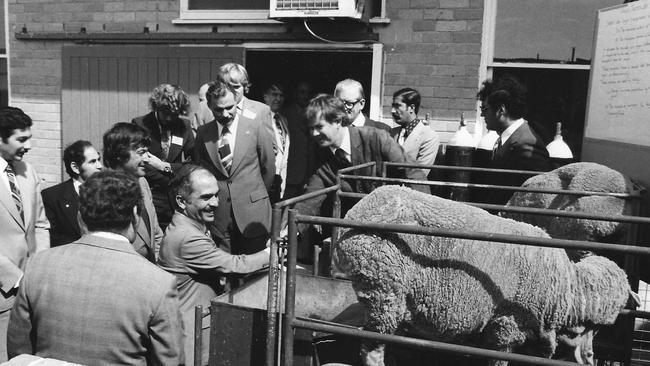

On his return to the bustling commune on the side of the Princes Highway in 1977, interest was buzzing.

Wood and his colleagues were vigorously researching human IVF in competition with UK gynaecologist Patrick Steptoe and embryologist Robert Edwards, and asked Trounson if he would join the team.

Trounson, who was conducting micro surgery on sheep to remove parts of their fallopian tubes as part of the team at the Queen Victorian Hospital, eventually agreed to come aboard in 1979.

But he had one condition: the team would have to switch to his method.

“I changed the whole form of the IVF methods to the way we would do it in animals,” he said.

In 1980, the team at the Royal Women’s Hospital in Melbourne made a major breakthrough using Steptoe and Edwards technique of collecting an egg just before natural ovulation.

They had created Australia’s first ‘test-tube’ baby, Candice Reed.

The following year, Trounson, alongside gynaecologist colleague John Leeton and

Wood struck gold.

His method had created the world’s first baby using fertility drugs for producing multiple eggs.

The young scientist from Orange stood on stage at the World Congress of Human Reproduction in Berlin in 1982 and shared his discovery with the world.

“I was speaking at the conference and the chairman said: ‘you’ve used up all the time’ and the whole audience jumped up and shouted at the chairman ‘let him continue’,” he laughs.

“The next 14 pregnancies happened very quickly with what we were doing. It was a totally different method, and was rapidly adopted worldwide.”

By 1984, another breakthrough; Zoe, the world’s first baby born from a frozen

embryo had been a success.

“It was a eureka moment,” professor Trounson said.

“If you’re an optimistic person and you believe it can work, then you just keep working until it does.”

Trounson’s research at Werribee had helped revolutionise the IVF success rate.

Hopeful mothers would undergo fewer operations to retrieve eggs and eggs could be safely reserved for future use.

The now Melbourne-based emeritus professor said he never really thought about how popular IVF might become.

“I just thought about it as a science; the thing that I was doing,” he said.

“I wasn’t really aware of infertility, much of the university in the 60s, we were primarily avoiding pregnancy.

“But I learnt to understand the depth, the pain of infertility for couples.”

Today, more than 10 million babies have been born through IVF.

These days, the distinguished scientist and his wife are focused on expanding the method overseas.

“The people in Africa and Asia came and said: ‘why can’t we have IVF? why can’t you do something for us?

“And so we’ve created low cost IVF, and we run clinics in Africa, where the more disadvantaged people can have children for a few hundred dollars.”

Professor Trounson said the price Australians are paying for IVF is “ridiculous”.

“It’s really a push by the companies that are involved,” he said.

“I know there’s some people spending absurd amounts on this.”

A community like no other

Professor Trounson recalls the sound of the children’s laughter, the patter of their footsteps on the gravel as they boarded the school bus on the edge of the farm.

“There were houses on or associated with the farm and I’d wander up from the quarters and see the kids running onto the bus, going to school, or in the afternoon, if you came back early, you’d see them playing around the farm,” he said.

“Sometimes you’d end up having dinner with the families. It was a unique environment.

“The farm had its own sort of social culture.”

Professor Trounson said the relationships he built at the SRF strike him as the fondest memories of his time there.

“It was an intersection of people from different backgrounds, where a lot of innovation was happening.

“Other scientists had their own particular interests but we would come together and be interested in what each other were doing, apart from talking about football.

“It was one of those really special environments.”

Researcher Dr Monika Schott, who has produced a short film about the farm in collaboration with Arts Assist and the Department of Jobs, Precincts and Region, said without the community at the SRF, the familiar supermarket items we take for granted today may never have graced the shelves of our local Woolies.

“Without these people and their families, we may not have things like powdered milk and flavoured yoghurt and a whole myriad of things in our supermarkets today,” she said.

“There was a strong social structure that had its own life.”

Mice milking, pig dissection and a grave of radioactive cows

Walking through the eerie buildings more than 20 years on from its closing, Trounson is struck by a sense of sadness.

It’s as if the last to leave put down their tools, crossed off the last day on the calendar, slipped books back onto the shelves and simply walked out.

Laminated no smoking signs remain stuck to doors and old phones still plugged into power points.

But the space, structurally left very much the same, could not feel more different to professor Trounson.

“It’s very strange because when I was here before it was such a lively place, full of people and full of animals and full of things happening all the time,” he said.

“And now, it’s a dead place. There is nothing here and it’s decaying … it’s a skeleton of what it was.”

Stationing himself between the surgical lights that once lit up the insides of dozens of pigs as Trounson searched for answers to the question of infertility, the silence, he says, stands in stark contrast to the brilliance of its glory days.

“Time takes a toll on everything, but it was magnificent work that was being done there, particularly through the 70s 80s and 90s, that truly was fantastic.

“That’s the nature of things, they change and pass.

Some of those experiments were stranger than others, Dr Schott says, standing beside a white board scribbled with notes, now decades old.

“The story of the radioactive cows has become a mysterious legendary tale.

“Depending on who I talk to about them, some believe it to be true, others say definitely not.

“But what certainly happened here were things like milking mice for cancer research, dissecting pig parts that we now use for human heart surgery.”

“It’s the kind of stuff you could only ever imagine.”

111 years on, what will it become?

Since operations came to halt in the late 90s and homes on the land were demolished, one question has loomed: What next for the farm?

The 2022-23 Victorian Budget provided $2.8 million to the development of the National Employment and Innovation Cluster (NEIC) within the western suburbs of Melbourne, but solid plans for the 775 hectares of land are yet to be determined.

“We are continuing to develop a strategy for the East Werribee Employment Precinct and how the former State Research farm land can be transformed over time,” a government spokesperson told the Saturday Herald Sun.