VWeekend: Why Martin Pakula loves life after politics

Former state attorney-general and sports minister Martin Pakula has opened up on the challenges of his role during the Covid pandemic, why he doesn’t miss politics and how he’s revved up about steering next year’s Australian F1 Grand Prix.

VWeekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from VWeekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

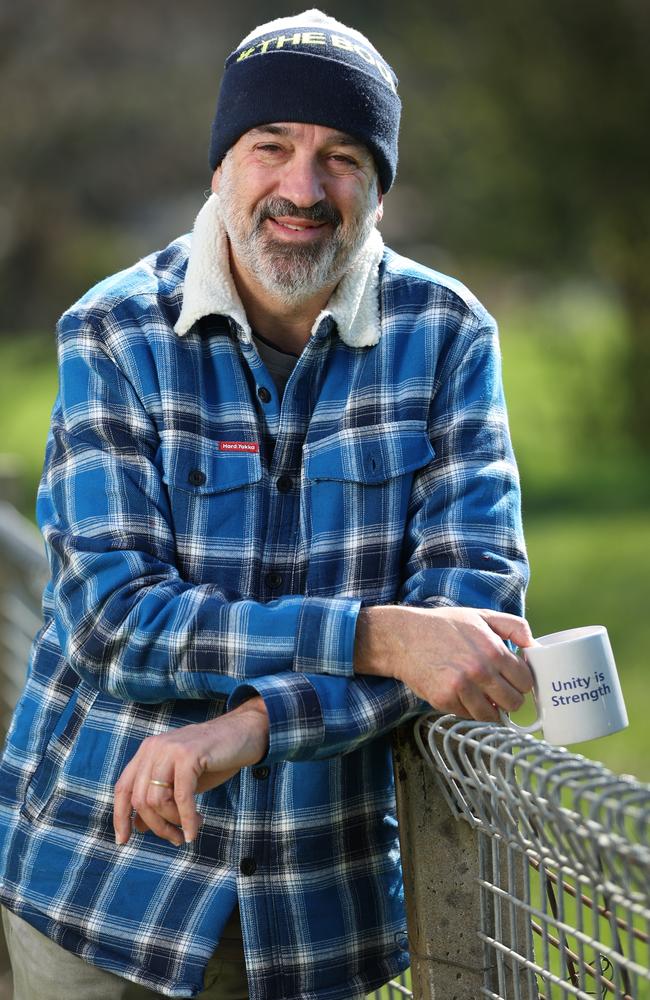

At the back of a modest fixer-upper property in northeastern Victoria stands a man dressed in a flannel jacket, beanie and boots, sporting an overgrown grey beard.

“I hope you didn’t expect me to dress up,” he jokes.

Martin Pakula, who once led the justice system in Victoria as the state’s attorney-general and is now the chair of the Australian Grand Prix Corporation, is with his wife Lisa at their King Valley weekender.

He looks the part of a weathered bushy, but quickly downplays his country credentials with a stern reminder he lives in Black Rock and is a “proper bloody Melburnian at heart”.

“The next door neighbour showed me how to use the pump, I’ve managed to work out how to swing an axe without chopping my toes off,” he says. “I bought a lawnmower and I’ve just bought a chainsaw which Lisa is convinced is going to be the end of me, or at least one of my fingers.”

But as we drive around popular pubs and wineries in the region, he chats to owners and staff like they’re old mates and points out attractions like a local.

Pakula has always been a bit of a chameleon, able to switch effortlessly from flannels to formal wear.

As an official at the National Union of Workers, his mentor, Greg Sword, told him that bosses feared seeing them in the boardroom more than “standing on street corners banging drums” and he was told to wear a tie to work.

As an eight-year-old he switched from Ormond Primary School to Haileybury College, thanks to a scholarship he baulked at accepting.

“I went from wearing a pair of dirty old jeans and a T-shirt to putting on a little pink cap and a tie and a blazer and thinking, what the hell is this?”

Pakula, who entered state parliament in 2006, served under three Labor premiers and rose to become first law officer of the state.

But his prominence grew during the pandemic when he was industry, major events and racing minister in Daniel Andrews’ Crisis Council of Cabinet.

In a rare exclusive interview, Pakula reveals how difficult it was to balance life and death decisions with keeping major events and tourism institutions alive, and why rejuvenating the CBD can make next year’s Grand Prix the best ever.

Pakula doesn’t miss politics.

“All I know is I’m sleeping better, eating better and feeling better since I left,” he says.

He points to social media to illustrate his point. “I haven’t been a minister for over two years, but I can’t send a tweet about the footy or about a rock band without someone saying, ‘Why don’t you shut up you piece of shit’, and I’m like, ‘how is that necessary?’” Pakula says.

“By the time I left in 2022, it was a much more unattractive way of life than it was even in 2006 when I entered. That’s partly social media. It’s partly the overhang from covid which was horrendous. It’s partly that everything, everywhere is more febrile.”

When Scott Morrison revealed he had battled anxiety during the pandemic, Pakula applauded the former prime minister’s candour, only to receive a torrent of abuse.

“I agree with Scott Morrison on pretty much nothing, but I sent a tweet saying I’m really glad to see him open up on that, because it is difficult, and that period of time was horrific,” he says. “I’m not for a moment saying that what we went through as politicians was as bad as people who lost loved ones or businesses which went broke, but it was pretty bloody awful for us, as well.”

Pakula won’t switch off social media; sitting in silence isn’t his nature.

During his political career he was known for speaking plainly, including during the pandemic when he had to advocate for industry and businesses to reopen.

“One of the things that I was always focused on was that this thing is going to end one day, and we need these institutions to still be here,” he says. “Whether that was Sovereign Hill or the Phillip Island penguin parade, or our CBD theatres, you didn’t want what was going to be a one year or two year health and economic event to mean that these things were all then gone forever. It was about keeping them alive.”

He acknowledges a lot of people disliked some government actions, some of which were panned by a federal review, but that context must be remembered. “The further into the distance Covid recedes, the easier it is to remember how much we disliked lockdowns and the harder it is to remember why they happened – a novel virus, no immunity, no vaccines and millions of deaths worldwide,” he says.

“Notwithstanding that, a good friend of mine said, ‘Next time, I think people would rather die than go into lockdowns again.’

“He might well be right, but that’s a pretty scary bloody prospect. Let’s hope there isn’t a next time.”

The Melbourne CBD needs a rev up, Pakulasays. The Australian Grand Prix chair, who was appointed to the role last year, says getting more workers back to desks would help.

“I’ve always supported having more people back in the office more often,” he says.

“The public sector and the private sector both need to pull their weight to make that happen.

“I think the CBD is more crucial to the cultural and economic life of Melbourne than the CBDs of other capital cities.

“Our strength is events, restaurant culture, theatre culture, bar culture, coffee culture. You need a vibrant city for that.”

He acknowledges that Covid-19 decision-making had a large bearing on this.

“We were probably too ready to accept the idea that the world of work was going to be radically different after Covid,” he says.

“I think now there’s a fair bit of recalibration happening and it needs to.”

But Pakula bristles at commentary of the Andrews government, criticising lockdowns while taking aim at 768 deaths linked to hotel quarantine breaches.

“You can’t attack us for keeping people at home, and in the next breath attack us for allowing people to die,” he says.

“If you are arguing for more openness, you are implicitly arguing for more infections and more hospitalisations. I knew that, when I was arguing for it. I knew that there would be a price for saying, ‘Let’s allow greater density in restaurants, let’s allow for more people back in the office.’

“It was about trying to find that balance.”

Pakula says Albert Park’s Formula One race next year, the first on the global calendar during the sport’s 75th anniversary, will be huge.

About 120,000 people have signed up to the GP’s “pre-registration”, with a 42 per cent increase in international registrations.

“Off the back of Covid, the Formula One Grand Prix is one of very few global events that actually has the capacity to move the dial in terms of rejuvenating tourism and generating value for local businesses,” he says.

At the Mountain View pub in the tiny town of Whitfield, Pakula sips a glass of wine while consulting his form guide.

“I still love the neddys,” he says with a grin, before musing that this King Valley venue recently won Tony Leonard’s pub of the year on 3AW.

Following his decision to quit politics, and with children Ben and Eva now adults, Pakula and his wife Lisa bought their weekender “shack”.

Although there has been a shift in lifestyle, Pakula has no intention of taking his foot off the gas.

As well as his unpaid Grand Prix duties, he’s on the boards of Helloworld Travel, the Sport Australia Hall of Fame, and Grande Experiences, which runs the Lume gallery.

Next year he will become chair of Tourism North East.

Pakula is also a major projects adviser to the AFL, working on the establishment of a new Tasmanian team and potential Gabba redevelopment, and is “back on the tools” doing legal advisory work for clients including the Victoria Racing Club.

The work is busy, but at a lower temperature than in a political cauldron where he became increasingly frustrated at an “absence of nuance” on issues as diverse as climate change, the Middle East, and gambling advertising.

“The instinctive demand on every issue is adherence to an individual’s personal dogma, or it’s a demand for a total ban on whatever they disapprove of,” he says.

“The reality is that most issues are complex and dominated by shades of grey. Debating nuance and finding a way through is difficult and time consuming. It takes effort and understanding. Being an absolutist is easy, but it’s incredibly lazy and disrespectful.”

As someone who once aspired to be a journalist, like his Aunt Zelda, Pakula quotes renowned American journalist and satirist HL Mencken.

“For every complex problem there is a solution which is clear, simple, and wrong.”

Pakula is baffled by the “caricature” of Daniel Andrews.

“He’s not a cartoon villain and he’s not the archangel Gabriel; he was an ambitious, hard-nosed leader,” he says.

“For me the two things that stood out about him were an absurd level of resilience, and a supernatural willingness to ignore his critics.”

During his farewell speech to parliament, Pakula said the pair had their fair share of “boisterous disagreements” but that the ledger was squarely in the premier’s favour, and that people who tried to make them out as internal enemies misunderstood their ambition for the government and the state.

Nevertheless, he was occasionally touted as a potential alternative premier by ALP right-wingers agitating against Andrews who favoured his centrist approach.

Some critics – and allies – thought he lacked the relentless drive of other leadership aspirants, and Pakula himself spoke about wanting to remain a “relatively well-balanced person” rather than a slave to the job.

He has maintained outside interests and kept friends from childhood in the southeast suburbs.

The switch from public to private schooling came after his late father Lou, who ran a small suburban legal practice, convinced him to sit for a scholarship with the promise that even if he won one, he could make the decision on changing schools.

“We got a call from the headmaster saying, ‘you’ve topped it’. I remember clearly thinking: ‘Oh that’s interesting but I’m not going’, and dad said: ‘Oh no, you have to go’,” he says.

“I’m not crying poor but there was no way my folks could have ever afforded to send me to a private school.”

As this story was being written, Pakula and his two sisters were rocked by the death of their mum, Adele, following a battle with dementia.

“My mum’s death is very personal to me, so I’ll just say this – if you’re lucky enough to have a nurturing and loving mum it gives you a sense of ballast and security that sets you up for life,” he says.

“That’s what we had, and maybe one benefit of being out of the day-to-day craziness of politics is that I was able to spend more time with her at the end of her life.”

Both of Pakula’s parents were the children of Eastern European Jews who escaped 20th century atrocities in Poland and the former USSR.

Adele started life in a displaced persons’ camp in what is now Uzbekistan in 1944, and became a teacher later in life.

Lou was born in Carlton; Lou’s parents were the only members of his direct family to make it to Australia – the others died at the hands of the Nazis.

Lou encouraged Pakula to study law at Monash University. He credits a powerful memory for delivering top marks at school.

“My head is full of a bunch of useless facts,” he quips.

“Every Brownlow medallist, every president, every Melbourne Cup winner going back to the 1960s.”

Testing the claim, I ask who won the 1982 Cup.

“1982 was a great year, Gurner’s Lane won the Caulfield/Melbourne Cup double,” he says.

“I remember because I was only 13 but I backed Gurner’s Lane that year, even though I kind of wanted to see Kingston Town win.”

His love of racing bloomed when he became a union official and learnt of an obligation to contribute to the punter’s club on his first day.

“Dad couldn’t stand it,” he says.

At university, Pakula had joined the ALP club and the Fabian Society, run at the time by Bill Shorten, after developing an interest in politics as a teenager.

“When most kids wanted to be doctors, lawyers, footballers, I wanted to be a union official,” he says.

“I wrote to Bill Kelty when I was 16 years old, in 1985, asking if I could get work experience at the ACTU. I can’t remember if he wrote back.”

He tried his hand at commercial litigation but “it didn’t really float my boat” and in 1993 he was an unsuccessful ALP candidate in the safe federal Liberal seat of Goldstein under the guidance of Ann Barker and Joan Child.

National Union of Workers secretary and political powerbroker Greg Sword later offered him a job and taught him that to be a good union official you needed “head, heart and balls”.

The goal was to be “hard-nosed and formidable without being gratuitously nasty and unpleasant”, and he took the same approach into politics 14 years later.

“You can be effective and you can be formidable and you can be a good politician without being an arsehole,” he says.

“It’s a long life.”

Pakula’s entrance to state parliament came after an unsuccessful tilt at Labor legend Simon Crean during a preselection for the federal seat of Hotham.

“That was an ‘eyes bigger than tummy moment’,” he says.

He was quickly shuffled into Cabinet by then-premier John Brumby and stayed on the frontbench for the rest of his career, but reveals he considered leaving after just one term due to Labor being dumped from government, and also eyed the exit in 2018, before reconsidering.

He knew it was finally time to go in 2021 when colleague Gabrielle Williams called to sympathise after his seat of Keysborough was abolished due to electoral boundary changes.

“I hung up and I thought, ‘I just didn’t give a shit’ … that’s a pretty good sign that it’s time to go,” he says.

Pakula says exhaustion from the pandemic wasn’t the defining reason he left politics; he still wants to do “one more thing” while young enough, at the age of 53.

He says no one wants to linger on the subject of the pandemic, because for two years they talked about “nothing else”.

“Not about footy, not about food and wine, not about travel,” he says.

“People had just had it.”

Sitting in the High Country as the vines change colour and the evenings lengthen, it seems the perfect setting to talk footy, wine and travel.

When the conversation is steered back to the pandemic, Pakula sums up his experience at the coalface.

“Economic livelihoods, life and death; you could be in politics in an era where you don’t have those kinds of challenges,” he says.

“If you can kind of navigate them and come out with your sanity intact, you’ve probably done OK.”