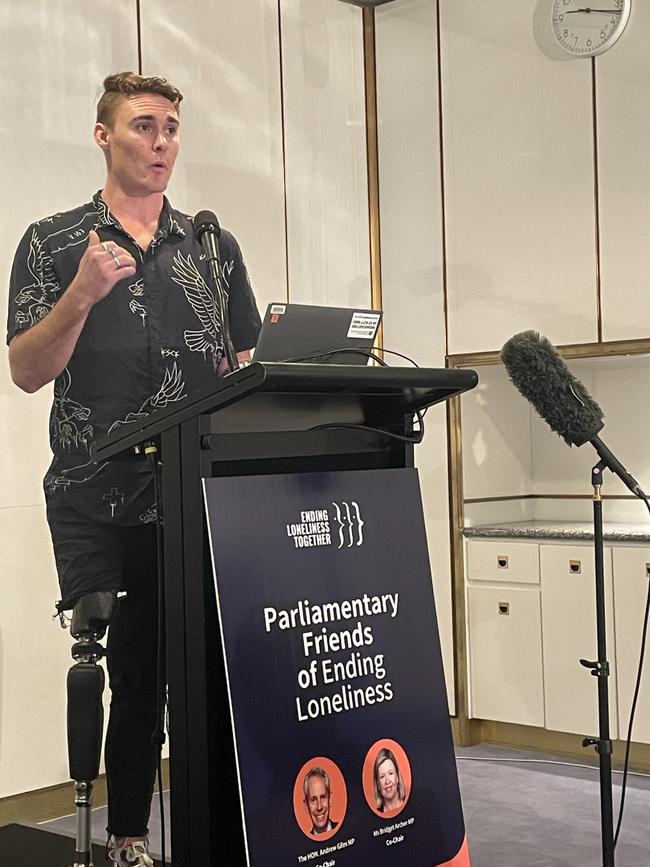

Joey Fry opens up on his battle with loneliness and why we need to make it part of the national conversation

More people than ever are feeling lonely and it’s the young who are suffering more than elderly. Joey Fry has travelled back from the greatest depths of loneliness and is sharing his story so others don’t suffer like he once did.

VWeekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from VWeekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

The worst night of Joey Fry’s life was not the Christmas Eve where he attempted to end it.

What was infinitely worse was waking up in intensive care six days later, to the abject grief in his mother’s eyes, and the news his right leg had been amputated.

It was December 2019, just a few months shy of a global pandemic that would take hold and cause widespread fear, confusion and isolation.

For the outgoing, and popular, young Newcastle tradie though, it had been the first time in his life he’d really felt alone – and it would lead to a decision devastating not only to him, but to his tight-knit family and loyal friends.

It would be his best friend who would find him slumped between his bed and the wall on Christmas Day. He’d been lying unconscious for so long, with his left leg laying heavily on top of his right, that the circulation in that leg had been cut off, the blood within it turning toxic, the muscles dying. While medical staff saved Fry’s life, they could not save his leg.

“In 2019, I went through a really turbulent time in my life. I had a split with a longtime partner, and my roommate at the time moved out, that left me living alone for the first time as an adult,” Fry tells Sydney Weekend.

“So over the next six months, I went through this self-sabotage downhill spiral. And looking back on that now I can now say that that’s the first ever time in my life I was experiencing severe loneliness.

“That led me to the decision I made on Christmas Eve to try and attempt to take my own life.

“I woke up six days later, in the ICU to mum standing over the top of me; she said: ‘There’s been an accident and you’ve lost your leg. They’ve amputated above the knee on the right hand side.’

“And that is the truly most heartbreaking thing I’ve ever had to hear in my life.”

Fry, now 27, would endure a dozen more surgeries, and be fitted with a prosthetic leg. He’d undergo intense rehabilitation, which continues to this day. Yet as tough as the physical recovery was, his journey back to good mental health was just as painful.

“The physical recovery was a massive thing, obviously, to get fitted with my prosthetic leg and get healthy again, and then go out into the world. But the mental game was just as much as the physical game,” he says.

“You have to become used to your new body – as who you are as an amputee. And that meant also finding a new identity as well. So that was quite tricky to start figuring out who I wanted to be in this world.

“I didn’t pass away, I got a second chance … so I didn’t want to muck it up the second time around. I just didn’t know what that would look like or the person, the young man, that I wanted to be.”

Fry’s beautiful mother, his dedicated aunt, other family and friends helped get him through those tough few months, and years.

“During my time in hospital, I experienced things like guilt, shame, anger, all those kinds of feelings of loneliness again,” he says.

“At first it didn’t feel like a second chance … it still felt awfully new, very painful. I thought how’s life going to be better now that I’m a person living with a disability?

“There’s no silver bullet to that answer; it was a lot of hard work and a lot of breakdowns, a lot of tears along the way. But on the flip side, I felt things like love and compassion and everyone rallied around me.

“It took such a tragic event in my life, unfortunately, to realise the connections that I had right in front of my face.”

A RANDOM CHANCE

What also helped immeasurably was an opportunity that literally came out of thin air. A chance call to a radio station that led to Fry not only helping himself, but others experiencing loneliness, depression or suicidal thoughts.

He’d been listening to triple j when the song Blueprint, by Melbourne band Slowly Slowly, came on and he connected with the lyrics: “It’s been a while since I’ve felt at home/ First time in forever I don’t feel alone now/ Back to basics/ Back on my bullshit/ I’ll get the hang of it, you be my blueprint.”

After playing the track, presenter Bridget Hustwaite urged callers to share their “wholesome stories” and Fry did just that.

“I said, ‘Well, what’s more wholesome than a formerly depressed, lonely, now one-legged man that’s got his life back together and starting to feel these wonderful emotions again, and can relate it to this song somehow,” he says.

“So I rang in and we had that chat on air, and yeah, just unknowingly changed my life for the better.”

Among those listening in that day was Shannon Swan, an award-winning Melbourne documentary filmmaker who was desperately looking for the right protagonist for his new project – The Great Separation. Swan, behind social insight documentaries such as Lygon Street, Gurrumul and We Were Once Kids, wanted to shine a spotlight on loneliness – its effects on the individual and society.

According to a 2023 State of the Nation report by the Ending Loneliness Together network, almost one in four Australians feel lonely most of the time – with one in six experiencing severe loneliness.

Contrary to the stereotype of older, lonely people, the snapshot of more than 4000 Australians showed that younger people were most likely to be lonely – with 22 per cent of 18 to 24 year olds reporting they often felt lonely compared with just 5 per cent of those aged 75 plus.

Australians who feel lonely are more than four times more likely to have both depression and social anxiety, and twice as likely to suffer from chronic disease.

“In late 2021, Melbourne (and NSW) went through a series of lockdowns where many felt loneliness and isolation for the first time – but it’s not just a pandemic issue, it’s an issue that’s been around since the dawn of time,” Swan says.

“What the pandemic did for many was provide a window into what loneliness felt like.

“The statistic that one in four people experienced loneliness was a shock to me and I wanted to explore that through film, along with a friend of mine, (cultural observer) Simon Hammond.

“But we needed a hero to tell the story.”

Driving home one night, Swan flicked on the radio, and serendipitously tuned in to Fry’s story. He immediately pulled over and hung on every word. Tracking down his “hero” wasn’t a simple task as Fry had not left contact details with the station, but through the power of social media the two would eventually connect.

“I went to Newcastle to meet him, and he just wanted to tell his story – he had the right support around him and he was ready to tell it,” Swan says.

“He wears his experience so visually – you don’t have to constantly remind the audience of the trauma he has been through.

“He’s the everyday man, he’s real, and that’s what people will connect with – the story of someone who on the outside had an amazing life, but how it quickly fell apart and how brave he is to share how that happened.”

Swan says Fry’s story changed his own life “profoundly” and believes the The Great Separation – available on SBS On Demand from October 10 – will do the same for others.

The documentary follows Fry as he meets with everyday people, and experts in the field of social sciences and mental health, to discover the reasons why he almost ended his life four years ago.

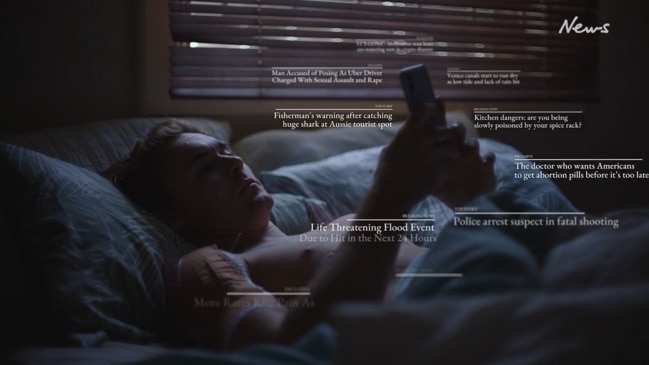

“The film covers what loneliness is, what forces separate us – whether it’s the way we build our houses, or use body language less, or spend more time on devices,” Swan says. “And it looks at how we can combat these things.

“It’s changed the way I interact with people – my own family, my friends, my neighbours.

“I now make it a priority to catch up with people face-to-face; I don’t turn on my phone before 8am and switch it off at night; we don’t have phones at the dinner table.

“There’s something in there for everyone – it shows how one change can change your life and the lives of those around you.”

For Fry, filming was cathartic too, as he searched for answers as to why he did what he did, and how he can stop himself from ever getting to that dark place again.

“I’ve never been in front of the camera before. I wouldn’t say I was a shy kid at all, you know, I was pretty outgoing, but I’d never done anything like this before,” he says.

“And I think one of the first scenes that we shot was the most emotional, in the way that Shannon really asked me some deep, dark questions about leading up to that night.

“And I quickly realised that I haven’t actually spoken about those kinds of feelings out loud to anybody, but I was okay doing it in front of a camera.

“I guess it’s just because I remind myself that I do want people to learn from my mistakes, and I have made a few mistakes in my lifetime. The best bit about that is the fact that we get to correct them.

“And that’s why I chose to be a part of the documentary. And then that’s also why I choose to keep sharing my story which at times is, you know, quite hard for me to share.”

He hopes everyone will take something away from the film that will help them when they’re feeling lonely, depressed.

“Everyone’s journey is different. I can only ever speak from a lived experience story,” he says.

“I put the walls up around my friends and family, when I really wished that I had just spoken up to somebody, anybody and really voiced the way that I was feeling.

“I let all of that sink into myself and it becomes very heavy, so if you’re just carrying on I really would suggest just saying something to anyone.

“And on the flip side, it’s such a simple conversation to have with a friend or a family member or loved one that can lead into bettering someone’s life.”

As for Fry, he’s enjoying time working down at the NSW snowfields – living in Jindabyne with a houseful of flatmates. A perfect example, if slightly hectic, of “social connection”, he says.

There’s a new dream too – with a chance meeting on the slopes perhaps opening a new chapter for this ambitious young man.

“I always had a love for the snow. I was a snowboarder when I had two legs. So it was a big goal of mine to get back on the snow in any way that I could,” he says.

“My amputation being quite a high one meant that I couldn’t put a prosthetic on a snowboard. So we tried skiing and after a few days a woman tapped me on the shoulder and asked how long I’d been doing it for and I said, it’s my fourth day. It turns out she has links with the Paralympic community.”

Now he’s serious about training to gain a spot in the Australian Paralympic team for the 2026 games.

“When I have the prosthetic on, everything’s a little slower, and more painful,” he says.

“Skiing makes me feel like myself again. I feel creative again and I feel inspired and it’s a really freeing feeling.

“I’m never going to say I’m fixed; I’m better, because mental health is always an ongoing thing. Being an advocate and an ambassador for good mental health means that I have to look after myself. And I’m doing just that.”

More Coverage

Originally published as Joey Fry opens up on his battle with loneliness and why we need to make it part of the national conversation