‘Here’s to a kind 1942’ were Val Shaw’s last words from Sorrento before he boarded a ship to hell

After many rejections, Vallance Shaw was happy to tell his mate he was finally going to war. He didn’t know where he was being posted. He didn’t know it was a doomed mission.

VWeekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from VWeekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Val Shaw picked up his cheap fountain pen.

He wanted to tell his dear friend, Jack Patterson, about the unlikely set of events which had plonked him near Sorrento, where he gazed at the boats at anchor and the petticoats on the main street.

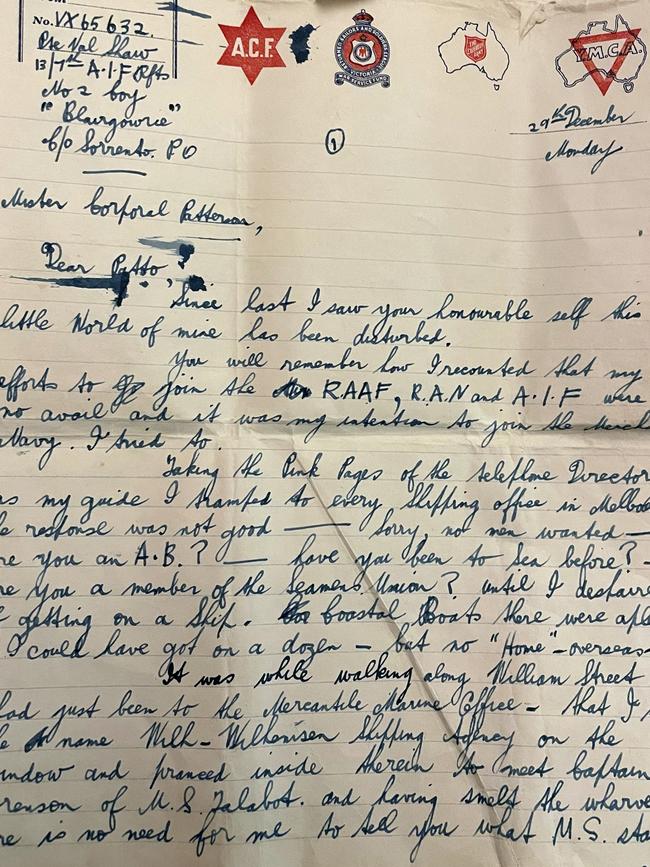

“Dear Patto,” he began writing. “Since I last saw your honourable self this little world of mine has been disturbed.”

Shaw was 23, an employee at the Argus, one of the city’s big metro newspapers in the 1940s. He itched to serve a country which fretted about the Japanese march southwards.

It appears that his eyesight was poor. Shaw had tried to enlist in the air force, and the army, and the navy. The armed services needed men, urgently, but they did not want Vallance Shaw.

Patterson, a cadet journalist, understood such exercises in dashed hope. He wanted to be a pilot, but had been rejected for flying for high blood pressure.

Shaw had refused to give up, he wrote to his friend. He had ripped out the pink pages of the telephone directory, and tried every shipping agency in Melbourne. He would join the merchant navy.

But he hadn’t been to sea, it was explained to him, again and again. He was not a member of the Seamen’s Union.

Shaw tramped down William St, to try yet another shipping agency. A Norwegian ship needed a deck hand and cabin boy for a six-month trip which would take in Hong Kong, Africa, America and Britain.

This was his ticket. All Shaw needed was a passport. He had photos taken in Flinders Lane, and popped into the Argus building, still preserved today at the northern end of the CBD, to say goodbye.

The next day, he went to the Immigration Office.

The “cold and officious bastards” there refused to process his passport.

There wasn’t enough time, they said. Anyway, Norwegian sailors could man Norwegian ships. Shaw “could have wept”.

As he wrote, the rebuttal proved fortuitous – the Norwegian ship was soon to be torpedoed and sunk by the “Yellow Bellies up north”.

And still, Shaw would not be put off. He returned, again, to the Australian Imperial Force office. Good news, finally. He could be enlisted in the postal unit.

But the postal unit, it turned out, was fully staffed.

Shaw was to join the artillery as a clerk.

Shaw had signed up at Royal Park on November 20, 1941. But things had taken an odd jag. As he wrote to Patterson: “Through some bungling – not uncommon in the Army – I found myself in the infantry and started my final leave within a week.”

He was going to war, a belated inclusion in the 2/21 battalion, which had trained together in Darwin for many months amid shortages of equipment, supplies and ammunition.

Shaw didn’t seem to know where he was being sent or what he was supposed to do.

But army brass did, and many senior Australian officers openly feared that the 2/21st battalion posting was a mission doomed to condemn hundreds if not thousands of Australian men.

Shaw had rushed to put his affairs in order – to that end, he was writing to ask if Patterson would serve as an executor to his will.

He probably wrote to his mother, Lily, at the house in Kew, and his brother Jack.

There was jauntiness in his voice, as if the generous loops of his cursive script described his excitement. He had made the most of his limited freedom; “I contrived to find happiness with a nurse from the Fairfield Hospital – I did.”

Yet Shaw had also walked the main street of Mornington, he told Patterson, and come across the avenue of trees for the fallen men of World War 1.

They had served in the infantry, machine gun and artillery battalions, even the Camel Corps.

The tribute “impressed me very much”.

“It all looks so very beautiful and peaceful,” Shaw wrote of the Mornington Peninsula foreshore, in the closing days of 1941.

“But over everything there is a strange vague feeling as if sitting on a time bomb and waiting for it to go off.

“I do not expect to be at Sorrento for long …”

“Here’s to a kind 1942.”

As Private Shaw wrote to Patterson in camp from his Blairgowie tent, a career colonel and decorated soldier was writing a letter to Army Headquarters.

Gull Force commander Lieutenant Colonel Leonard Roach was tasked with leading a defence of Ambon, a small island to the north of Australia.

Today, Ambon is an Indonesian wonderland rinsed in friendliness and spices. Then, it was a rundown Dutch outpost critical to Australia’s future.

It boasted a deep harbour and two airfields. If the Japanese seized Ambon, Australia’s mainland was imperilled.

Gull Force included the men of the 2/21st battalion. The bulk of them arrived at Ambon, now under imminent threat, on December 17, 1941. Roach would cite a near absence of automatic guns, artillery or naval and air support in asking for his men to be evacuated.

He had spoken of “unpardonable stagnation” in the planning for the Ambon campaign.

In his late December letter, he spoke of his “feeling of disgust and more than a little concern at the way in which we have been ‘dumped’ at this outpost position”.

By January 13, he raged about the “purposeless sacrifice” which awaited. Army HQ in Melbourne responded with cynical indifference and stripped Roach of the Ambon command.

On January 17, 1942, Roach was sent home to Darwin. The same day Shaw, the 2/21st battalion reinforcement, landed at Ambon.

Morale was low; defeat was expected, no matter whether the Japanese landed on the north or south of the island. If Shaw wrote to try and make sense of his unlikely destination, the words have been lost.

Almost 1200 Australian soldiers were stranded without hope or help when the Japanese invaded Ambon on January 30, 1941. One-sided skirmishes ensued.

Roach predicted the Allied defences would last one day; in the end, the Australian/Dutch resistance flared here and there over four days.

The inevitable Allied surrender of Ambon was just another fallen domino in a Japanese surge which engulfed the supposedly impregnable Singapore less than two weeks later. There, many green Australian soldiers, as with Shaw, were forced to surrender in their first weeks of battle.

Most tales about the capture of Ambon recall the one in four Australian soldiers who survived Japanese captivity for the next three-and-a-half years. Among the prisoners was Max “Eddie” Gilbert, the last surviving Gull Force member to march in Melbourne Anzac Day parades.

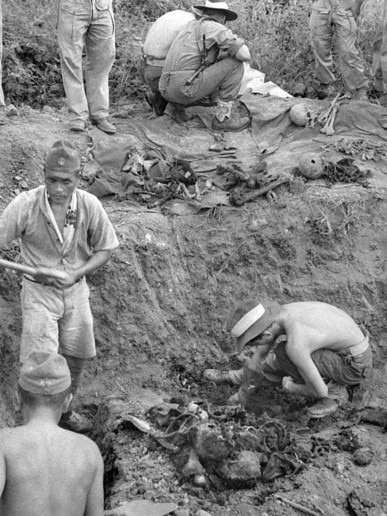

The Ambon massacres in the first days after the Japanese invasion are less remembered, mainly because no Australians were spared to speak of them.

These men just disappeared, poor Val Shaw among them.

It was only in 1945 that the Australian bodies – hands bound, many decapitated – were exhumed from mass graves in a coconut plantation. The evil of February, 1942 could finally begin to be understood.

Shaw’s official day of death would be recorded as February 20, or the so-called fourth massacre at the Laha airfield. The day before, the Japanese had marked their capture of this Ambon airstrip with the first of many bombing raids on Darwin.

About 220 men huddled to wait for the end. Some of the condemned waited six hours to die. Only one meaningful wish remained to them; that they might die cleanly and quickly, unlike some of their comrades who twitched and moaned in mass pits before death’s release.

The Australians were blindfolded, then beheaded or bayoneted.

In a later account, from a Japanese officer, cheering Japanese spectators gave “constant shouts of jubilation”, “mixed with ribald scorn as some prisoners begged for their lives”.

The night darkened; as it was later described, “several bonfires had been lit and cast dancing shadows on a spectacle reminiscent from the pits of Hell”.

Torches were produced to illuminate the victims’ necks.

The Japanese yelled “in revenge of so-and-so” as they swung. One Japanese officer observed that his sword had become nicked and bent.

The Ambon massacres were driven partly by revenge. A Japanese minesweeper had struck a mine in Ambon Bay; the commanding officer volunteered himself and some surviving men as executioners.

Four Japanese officers were sentenced to death for these atrocities at a later war crimes commission.

Their legal defence? Following orders.

Shaw’s letter to Patterson might have been the last he wrote. It was put in a tin box, for special keeping, along with love letters between Patterson and his wife, Winsome, and official papers.

There are no direct descendants to commemorate Shaw, just a skimp of a war service record which notes his missing status on the third page of five.

He was condemned to a whisper in misplaced hope and patriotism. Even the only known photos of him are a kind of consolation to a life unled, little more than a couple of mugshots which hint of kind eyes and a shy smile.

Jack Patterson visited Shaw’s mother Lily in her Kew home after her son’s death. It’s thought Shaw left him his car in his will, which Patterson refused to accept.

Patterson, like Shaw, fulfilled his wish. He would serve in the air force (on the ground) in the Middle East. He survived, to smoke a pipe and to bequeath a love of the Richmond football club which oozes from his great grandchildren today.

Winsome Patterson died long after him, aged 96, in 2017. The tin box was among her belongings. Shaw’s letter – and the irrepressible sense of purpose it described – had laid in statis for more than three generations.

To Patterson’s family, Val Shaw had always been the “friend who got beheaded”, a ghostly echo to be grieved with a sharp intake of breath.

The poignancy of Shaw’s final weeks – the impossible blend of anticipation and barbarity – haunted them.

Yet in reading Shaw’s words freshly, he became so much more.

In befriending a nurse, he at least experienced a joyful moment or two before the most grim of ends. He was a dreamer, a doer, and perhaps a writer doomed to never be.

Shaw had quoted a poet, Omar Khayyam, in describing to Patterson how he felt before he embarked on active service.

One Moment in Annihilation’s Waste,

One Moment, of the Well of Life to taste –

The Stars are setting and the Caravan

Starts for the Dawn of Nothing – Oh, make haste!

Khayyam wrote this poem in Persian about a millennium ago. Yet its message still resonates.

Life is short, he was saying. Seize the day, lest few days remain.