Ancient Egyptian treasures’ epic journey to Melbourne for Pharaoh exhibition

From a tomb wall that “nobody in our generation has seen”, to 10 towering statues of the goddess of destruction – these are the highlights of Melbourne’s new Pharaoh exhibition. WATCH THE VIDEO

VWeekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from VWeekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

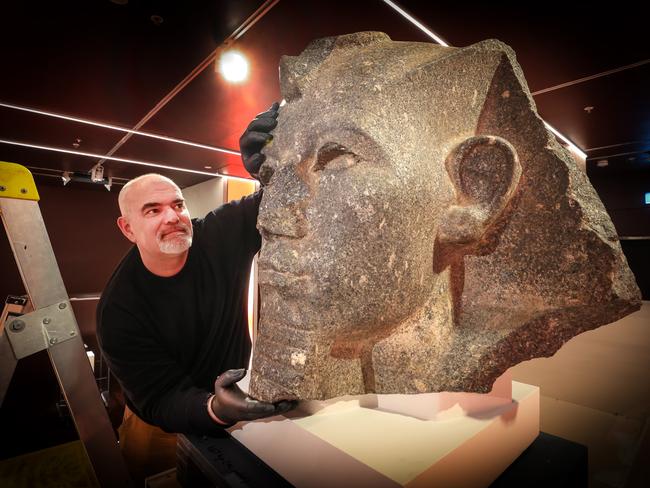

A grand lion statue immediately draws the attention of visitors to the British Museum’s world-famous ancient Egyptian sculpture gallery.

The powerful representation of 18th Dynasty pharaoh Amenhotep III stands out due to its size (2.16m long and weighing 2.5 tonnes) and excellent condition, given its age (more than 3000 years old).

The ancient treasure is normally displayed alongside a mirror-image companion. But that won’t be the case this year.

British Museum curator Dr Marie Vandenbeusch and her team selected it as one of 500 artefacts to be packed up and flown 17,000km from London to Melbourne, for Australian audiences to enjoy as part of exclusive National Gallery of Victoria exhibition Pharaoh.

The extraordinary loan to the NGV constitutes the largest exhibition the British Museum has toured internationally in its 270-year history, and the largest ancient Egyptian exhibition ever displayed in Australia.

As such, it has left several notable gaps within the sculpture gallery.

This is unusual, Vandenbeusch explains as she guides me through the space. She is typically restricted from leaving too many holes when she selects artefacts for travelling exhibitions.

“I usually try not to take too much from our display, because (we want our) visitors to enjoy it,” she says. “But because (Pharaoh) is a one-off (for Melbourne), I’ve been able to pick a few more objects in the sculpture gallery than I would usually.

“We really tried to build something unique for the Australian public.”

To further illustrate this, Vandenbeusch gestures to an empty case that is normally filled by a sculpture of Horemheb – another 18th Dynasty king, who ruled shortly after Tutankhamun – and his wife.

“It is one of my favourites, this representation of a general who became king,” she says, noting NGV visitors won’t want to miss it.

“There is no inscription, so for a long time, we didn’t know who it was. We didn’t know it was Horemheb until his tomb at Saqqara was excavated and they found a small bit of a hand from a statue and it matched perfectly.

“It really reflects all the things we still don’t know, and how we still learn constantly about life in ancient Egypt.”

The British Museum was the UK’s most-visited attraction last year, drawing 5.82 million people – more than Melbourne’s population — according to the Association of Leading Visitor Attractions. It’s swarming with tourists on the day of my visit. The Egyptian rooms are particularly bustling.

So the museum’s willingness to part with 500 artefacts for an extended period, to share them with NGV visitors on the other side of the globe, reflects a strong bond between the institutions. It also shows just how big a coup Pharaoh is for Victoria’s capital.

The Melbourne Winter Masterpieces exhibition has been in the works for more than eight years. It will cover the gallery’s entire ground floor from June 14, and celebrate the art and artistry of ancient Egypt by showcasing artefacts connected to the civilisation’s most famous rulers. This includes Tutankhamun, Ramses II and Queen Nefertari, Alexander the Great, and Great Pyramid of Giza builder Khufu.

“A lot of (the items) have never been displayed in Australia; some of them were never displayed in London,” Vandenbeusch says.

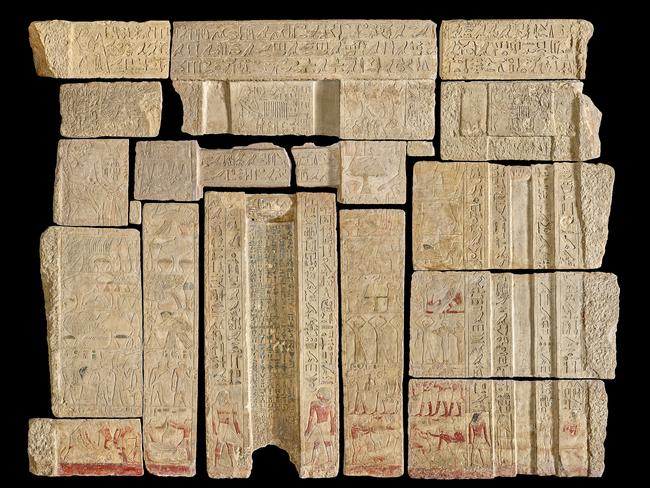

NGV visitors will be the first in a generation to see a limestone wall from a 4000-year-old mastaba, or funerary chapel, discovered near Giza. It stands about 2.5m tall and 3m wide, and is elaborately carved to reflect “all the things the deceased will need in the afterlife”.

“It will be rebuilt in Melbourne,” notes Vandenbeusch, an expert in funerary artefacts.

“Nobody in our generation has seen it all together. It’s quite exciting.”

In his 28 years at the British Museum, collection manager Evan York has never worked on a larger or more challenging international exhibit than Pharaoh.

The man responsible for getting the artefacts safely to and from Melbourne says his role began several years ago, when Vandenbeusch handed him a list of items she wanted to include in the exhibition.

“I decide what’s suitable for travel,” he says, noting this involves consultation with another colleague in the Egypt and Sudan department, conservator Stephanie Vasiliou.

“Then, I plan all the object moves from the store rooms and galleries, pack them and prepare them for the exhibitions by making bespoke modules and frameworks for travel, and mounts to display them.

“(My team) escorts them on the shipments to Australia. Then we’re on site installing them for the exhibition.”

York and his four-person team began packing items last June, assisted by the museum’s heavy object handling experts.

There is no one-size-fits-all approach to moving and packing ancient items. There is also no bubble wrap involved.

“We use different types of foam to hold things in place – depending on the different densities, the weight of the object, (whether) there are any existing breaks, the fragility of the object,” York says.

His team’s biggest challenge was managing the scale of Pharaoh. The museum has toured several large exhibitions in the past, but “this is bigger”, York says. “It’s much, much bigger.”

The scale of some of the individual artefacts also tested the collection manager – including the red granite lion statue whose twin remained in London.

“He looks nice and solid, but even granite like that is very delicate if you move it the wrong way,” York says.

“We’re sending several large sculptures for this exhibition – some weighing about 2.5 tonnes (like the lion). Some of these works have never travelled. Some haven’t moved for probably 30 to 40 years.

“Some of them needed bespoke steel frameworks (to be moved). Because some of them were so tall, to leave the gallery to be packed and transported to Melbourne, they needed to lie down.

“We use bespoke lifting and moving equipment – big forklifts, big trolleys and gantries.”

The artefacts were flown to Melbourne in hundreds of crates, and on a mix of cargo and passenger planes. They were stored alongside travellers’ luggage on the latter – although they would never know it.

“Security is taken very seriously,” York says. “Nothing is identifiable. We have couriers on all the flights.”

York and his team will “do it all in reverse” to get the items back to London, he says: “As soon as the exhibition closes, the de-installation starts the next day.”

From the 2.5-tonne lion to a 5000-year-old ivory label that was once attached to a sandal, and a 1.5-tonne fist detached from a colossal statue of Ramses II to ornate jewellery – the artefacts that make up Pharaoh vary dramatically and span 3000 years.

To put that time frame in perspective, Vandenbeusch notes that “we are closer now to Cleopatra than she was from Khufu and the Giza pyramids”.

“You can imagine how many changes you have between Cleopatra and now, so you need to expect those kinds of changes – in terms of the community, cultural input, economically and so on – during that time period,” she says.

A display of 180 pieces of jewellery will be a highlight of Pharaoh, Vandenbeusch says, adding the British Museum has never toured it as a collective before.

“The jewellery section was developed in collaboration with the NGV, for the NGV,” she says. “They were quite keen to have something unique.

“There are very few pieces of jewellery on display (at the British Museum).”

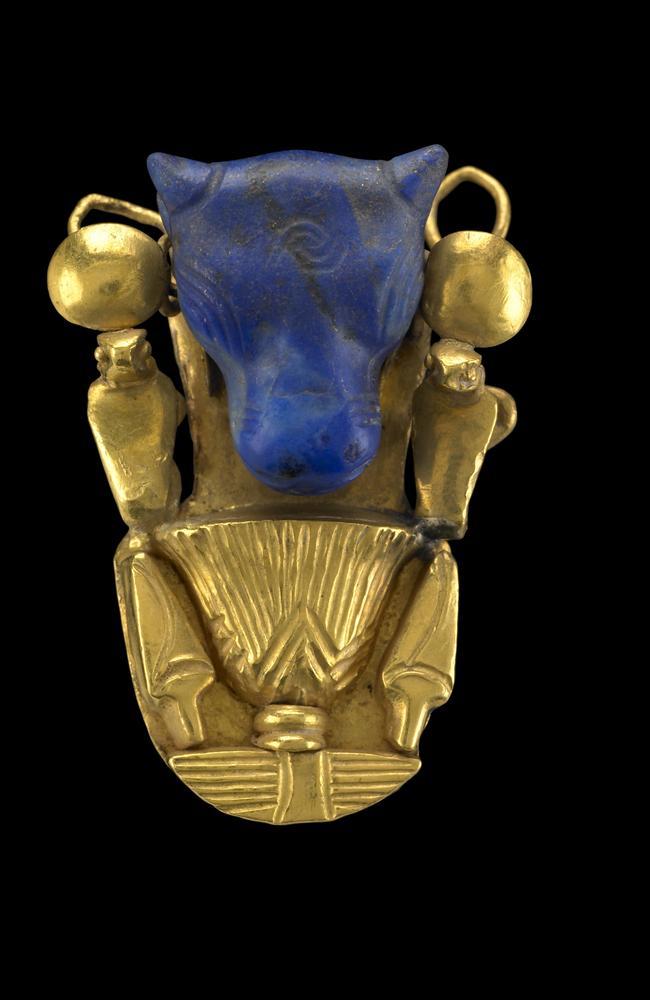

The necklaces, collars, girdles and rings showcase the sophisticated skill of ancient Egyptian craftspeople, who worked with gold, silver, electrum and semi-precious gems. A standout piece – a bull’s head ornament excavated south of Cairo – is made of gold and lapis lazuli, a deep-blue stone mined in Afghanistan.

Given the NGV is, at its core, an art gallery, it makes sense that at least part of Pharaoh highlights the artists of this society. One section focuses on the village Deir el-Medina, which was home to craftspeople who cut and decorated royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings.

“This … is an art slash archaeological exhibition,” Vandenbeusch says. “I really wanted to highlight the thousands of people that actually made the civilisation the way it was.”

At the opposite end of the spectrum from the jewellery pieces are the mighty stone artefacts.

As a senior conservator of stone, wall paintings and mosaics at the British Museum, Vasiliou was charged with ensuring these items looked their best for NGV visitors.

Her team dedicated about 2000 hours to conservation work on 70 stone-related objects. This included “anything from doing a light cleaning, dusting an object, right through to completely reconstructing things”.

“It depends on the object, what you’re trying to achieve with the conservation,” Vasiliou says. “We’re always trying to achieve stable – we want to be able to move it, handle it. Beyond that, we’re in discussions with curators about ‘what is the purpose of the object? What are we trying to achieve with the exhibition? What story is trying to be told?’

“You want them to look aesthetically nice, but we’re not making them the way they did thousands of years ago. You’re trying to make sure it’s visible to a degree that you’ve done the work.”

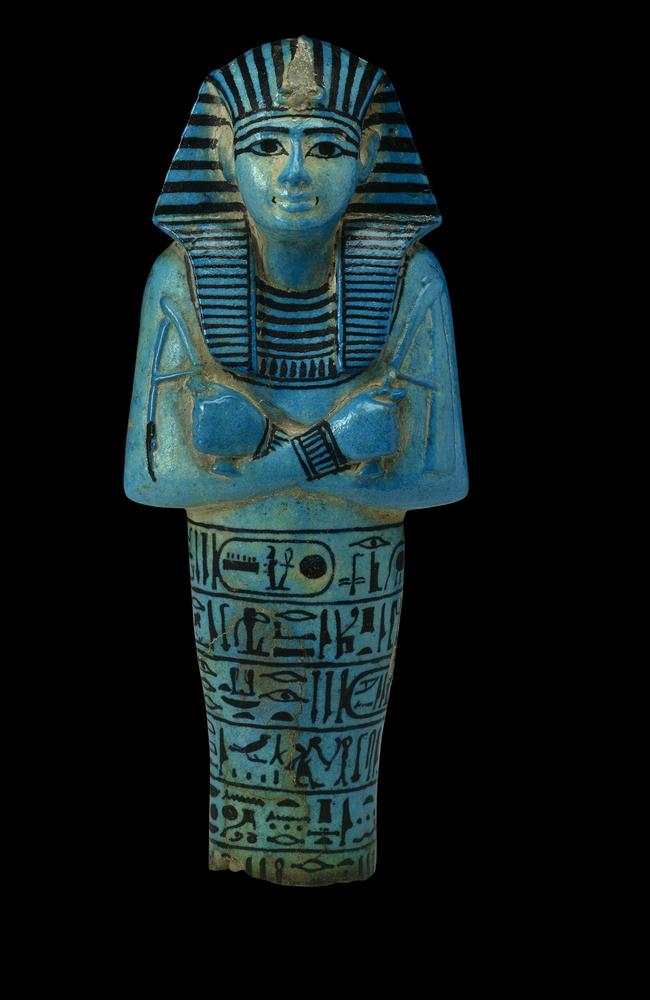

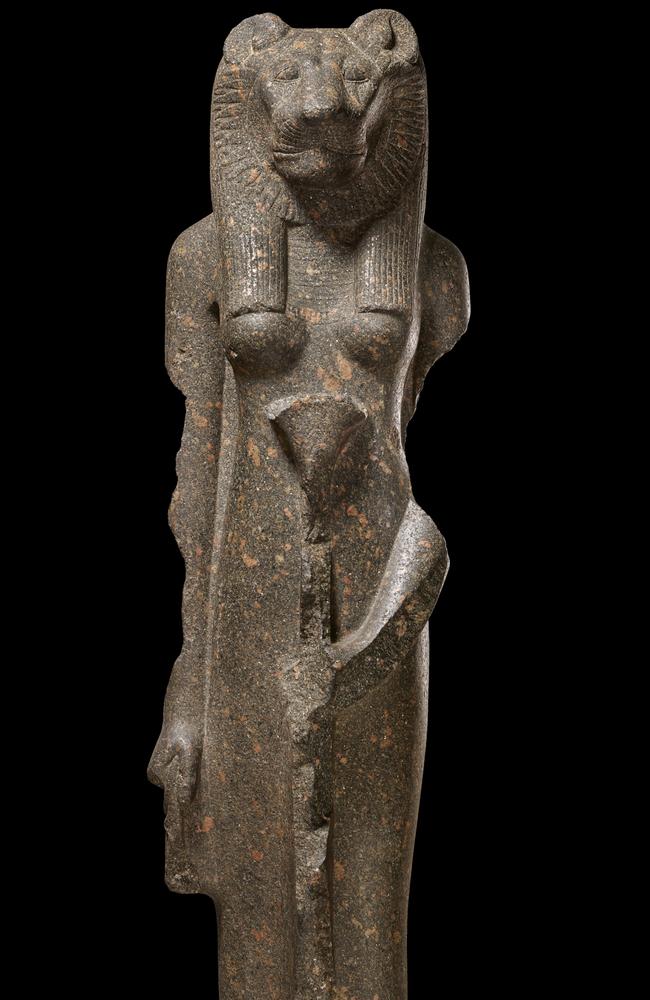

A statue of the lion-headed goddess Sekhmet – one of 10 that feature in Pharaoh – posed a particular challenge.

It had, at one stage, broken into two pieces around the stomach and been repaired. But that restoration had deteriorated while the grandidierite statue was in museum storage for about three decades.

Trying to move the Sekhmet out of storage as one piece would have involved precariously laying down the almost 2.5m-tall object. So the conservators took it apart, cleaned it and removed some of the previous restoration materials so it could travel to Melbourne in two parts.

This included having to cut through “very large steel dowels going all the way through from the (Sekhmet’s) chest region into her seat” with a saw, and using a laser to strip off a cement-like coating that had been applied several decades earlier.

When the statue arrived at the NGV, Vasiliou and her team used lifting equipment to pick up her top half and “slot her in, on to her base (so) she can be appreciated”.

Dr Daniel Antoine – Keeper or head of the British Museum’s Egypt and Sudan department – has been captivated by ancient Egypt since he was a child. He’s certainly not alone in that fascination.

“Some cultures have almost become world cultures because of the unique interest in them,” he says. “Look at the fact there are thousands of Egyptologists outside Egypt and outside Africa … whereas, there are very few Anglo-Saxon specialists outside Europe.”

He puts this down to the fact that dry conditions experienced in the deserts of Egypt allowed for remarkable preservation of organic materials, like papyrus. As a result, the texts recorded on these materials survived, providing modern scholars with a “rich and nuanced understanding of this culture”.

“That gives us insights into poetry, literature, divorce settlements, taxation records – all this detailed nuance that we miss in a lot of other cultures,” he says.

Vandenbeusch agrees preservation has been vital to ancient Egypt’s enduring appeal.

“To have access to the mummified remains of people (also allows researchers) to better understand who the people were,” she says. “And if you read the newspapers, every few months, there is a new incredible discovery. That keeps people interested.”

For Vasiliou, the skill and ingenuity of the people who made the artefacts she conserves still blows her away.

“Grandidierite, basalts, red granite – they’re durable, hardy stones,” she says. “If you were to drill into it grandidierite today, you would need a diamond-tipped drill. So how they carved it is amazing.”

Antoine hopes Pharaoh will captivate Australian audiences and ultimately “inspire them to visit Egypt”.

“I’m really looking forward to the NGV putting a slightly different twist on presenting ancient Egypt (and) highlighting the evolution of the art and how royal power was depicted over time,” he says.

The writer travelled to London with assistance from the NGV.

Pharaoh is at NGV International from June 14-October 6. Dr Marie Vandenbeusch will host an opening weekend keynote talk on June 15, presented by HSBC, about The Making of Pharaoh.

ngv.vic.gov.au/exhibition/pharaoh

PHARAOH HIGHLIGHTS

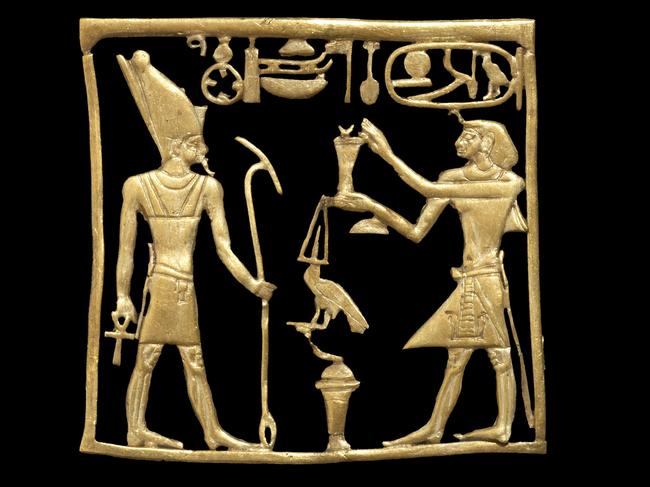

Statue of Horemheb and his wife

An exquisite limestone depiction of the last pharaoh of the 18th dynasty of ancient Egypt and his wife.

Dr Daniel Antoine: “(Horemheb) has his left hand on her lap, and she’s holding it with her two hands. This level of intimacy reveals another side (of Horemheb). I believe he was still a general (when this was created). If the visitors go around the back, they can see that her wig is in the process of being carved and it’s been interrupted. It’s likely that he became pharaoh when this piece was being made and they discarded this to prepare a hard stone statuary instead.”

Mastaba wall

This limestone wall from an Old Kingdom mastaba tomb is elaborately carved with hieroglyphic texts and depictions of the tomb owner seated in front of offering tables.

Dr Marie Vandenbeusch: “It will be rebuilt in Melbourne, it’s going to be quite impressive. Nobody in our generation has seen it all together.”

Statues of Sekhmet

Amenhotep III ordered that 730 statues of Sekhmet, the lion-headed goddess of destruction, be created for his temple in Thebes, to welcome and appease her. Ten of these will be on display in Pharaoh.

Vandenbeusch: “I really encourage you to have a look in detail, as they are all quite different. To produce that many statues, you needed a lot of people – some more or less skilled, some adding a few details here and there.”

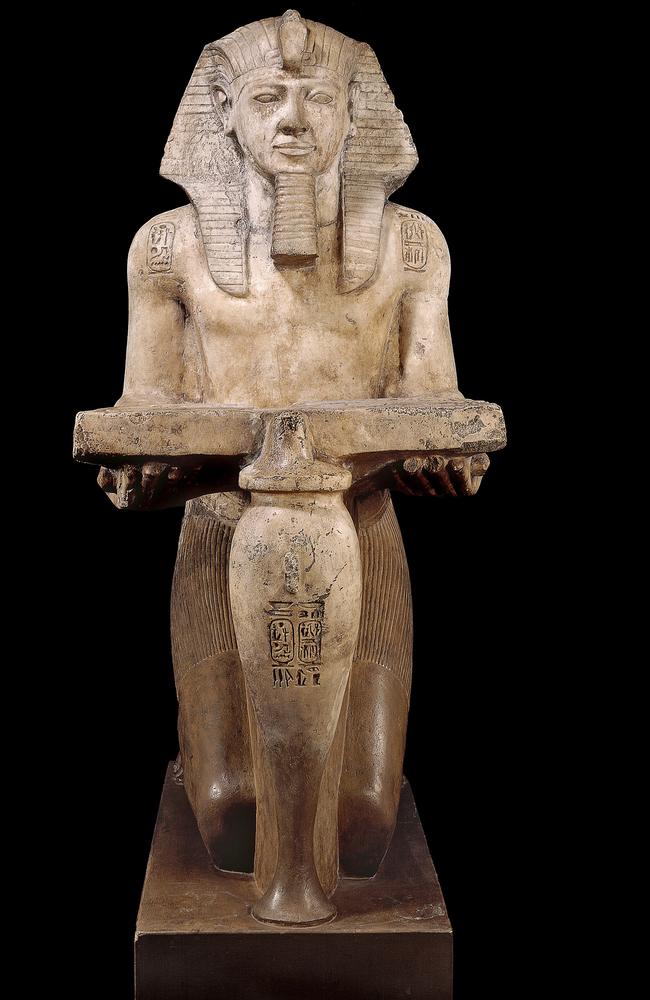

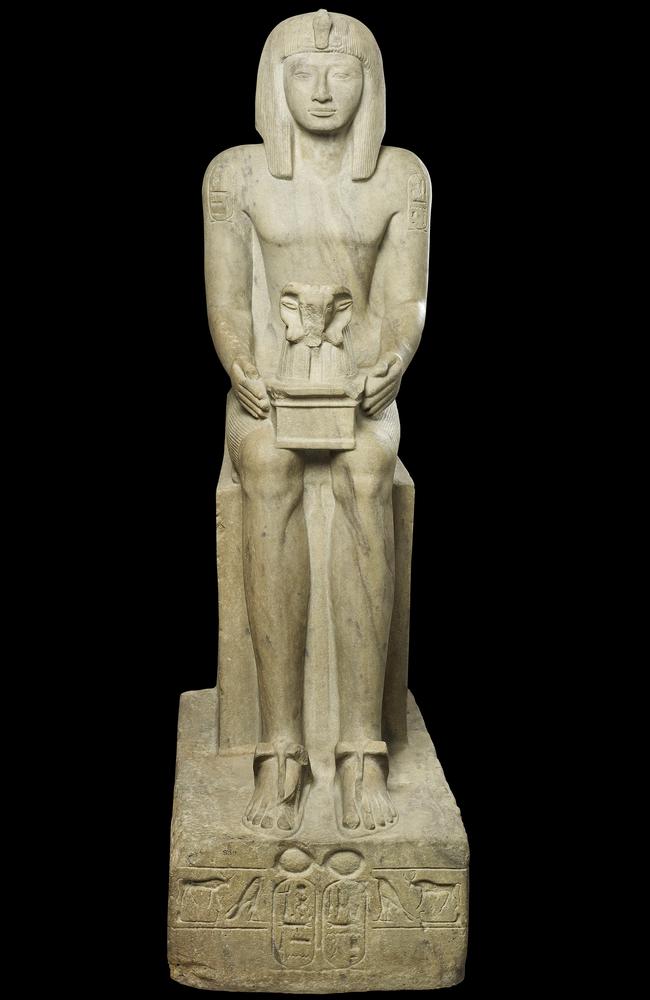

Seated statue of Sety II

Dating back to about 1200-1194 BCE, this is the most complete sculpture of a pharaoh in the British Museum’s collection.

Antoine: “It hasn’t been on permanent display at the British Museum for many years – it tours a lot because it’s such a spectacular, iconic piece. At 164cm (tall), a statue of this pharaoh in a seated position with the ram god Amun on his lap, it’s just a fantastic piece.”

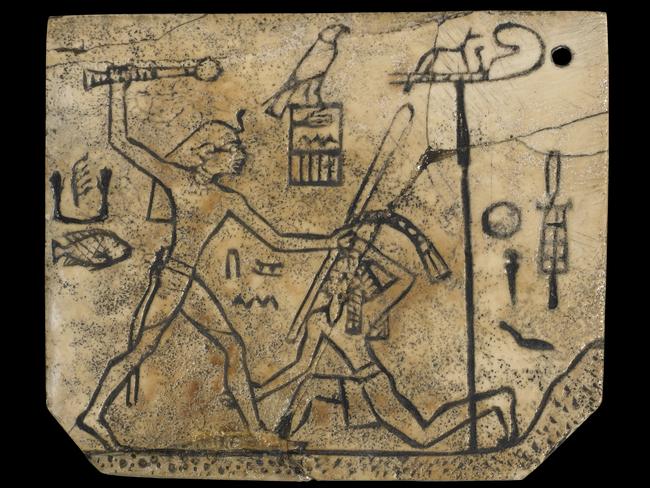

Ivory label with King Den

A small ivory plaque portraying King Den, one of the pharaohs of the first dynasty, that dates back to about 2985 BCE.

Vandenbeusch: “This is the earliest depiction of a king in the exhibition”.

Lapis lazuli bull’s head ornament

Made of gold and lapis lazuli, a deep-blue stone mined in Afghanistan, this is one of 180 pieces of jewellery showcased in Pharaoh.

Antoine: “The jewellery section adds a level of intimacy (to the exhibition, and) a very different perspective on power and projecting power.”

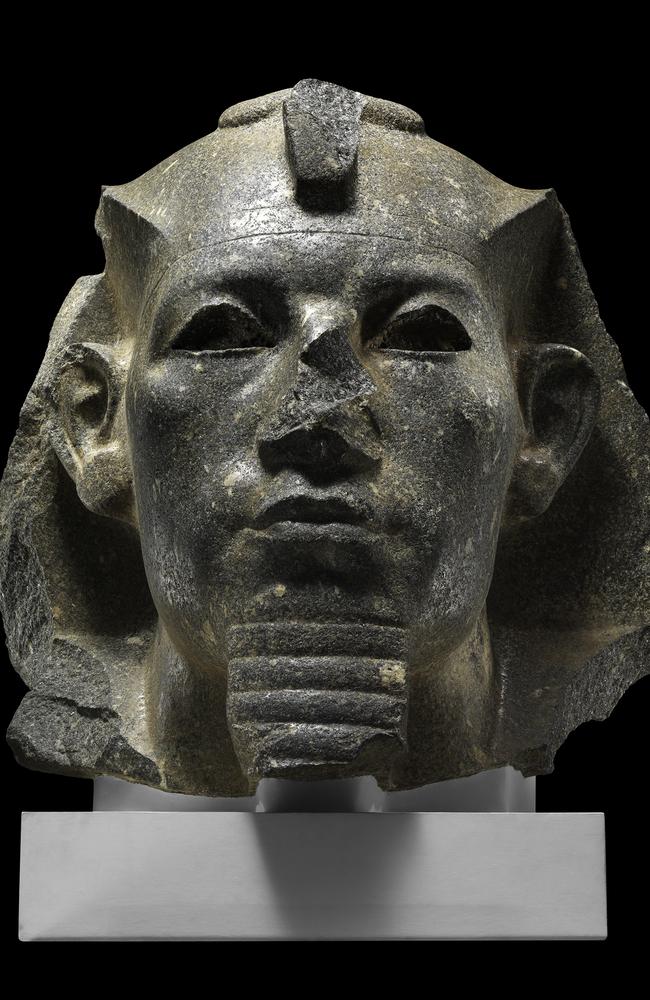

Statue of lion of Amenhotep III

This mighty representation of Amenhotep III is one of the largest pieces in Pharaoh. The red granite statue was uncovered in Sudan with a mirror-image twin. It has been re-inscribed by subsequent rulers, including Tutankhamun and Amanislo.

Vandenbeusch: “Most pieces don’t have just one story and one layer of narrative.”

Sources: Marie Vandenbeusch, Daniel Antoine