World-renowned artists on ‘what is art’ and why it must keep evolving

Artists have a message for traditionalists who may scoff at emojis, tennis balls and a banana being elevated as art as part of NGV Triennial.

VWeekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from VWeekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

An ordinary banana gaffer-taped to a wall at the National Gallery of Victoria elicits a range of responses from visitors.

“I love it,” one man says. “It’s silly.” His partner chimes in: “It’s a really good conversation starter.”

A teenage onlooker is less convinced, describing the work, Comedian by Italian artist Maurizio Cattelan, as “confusing”.

A woman from a group who can’t contain their giggles comments: “It’s quite thought-provoking, why someone would think that’s really funny. It’s making everybody who comes in here laugh.”

Laughter is a common response, as is the impulse to take a selfie with it. Two friends who do the latter have different takes. One muses: “Artists are in our lives to make it more interesting, to help us reflect on everyday objects and the world around us.

“I think art is intended to push boundaries.”

Her mate shrugs her shoulders and says: “We enjoyed it. (But) does it belong in a gallery?”

The same question could be asked about other out-there works in the NGV’s free exhibit, Triennial, including those that elevate robotics, emojis and tennis balls as art.

As for Comedian, can a piece of fruit store-bought and stuck to a wall with tape you’d find at Bunnings — albeit to specific instructions from the artist — be considered art?

At least a handful of cashed-up art collectors think so — the conceptual work has sold three times for between $188,000 and $235,000 since it was debuted four years ago. As does Ewan McEoin, senior curator of contemporary art at the NGV.

“Cattelan is a very respected artist. He has decided that he can put a banana on a wall and offer that to the world as his art, and he has every right to do that — as anybody has any right to make any artwork about anything,” he says.

“At its root, art is about people expressing themselves.”

What is art?

British contemporary artist Ryan Gander has created a diverse body of work spanning media including sculpture, film, writing, graphic design, installation and performance. But when he thinks about art, he can’t help but picture “the stuff that’s square and goes on the wall”.

“Art could always be anything. Throughout history, artists have made inventions, architecture, clothes, jewellery with great symbolism,” Gander says. “So I find it really weird – I mean, I do this, everyone I know does this – that we always think about art as paintings. That’s the first thing we think of.”

He is adamant, though, that art should be more than decorative.

“I’m interested in art that is like a very sophisticated, full-course tasting menu. I’m not interested in art that’s like going to KFC,” says Gander, who was awarded an Order of the British Empire for services to contemporary art in 2017.

“Art is everything that doesn’t answer questions, but only poses them. Art is meant to be the place where you can push boundaries, make mistakes, say ridiculous things, do things that are completely bonkers … that in any other section of society, you would be criticised for.

“Artists are meant to be creative and imaginative. And if we can’t get away from the fact that art is a square on the wall, there’s no creativity in that.”

Australian performance artist Smac McCreanor similarly refuses to “see any limits on media or formats or styles”.

“If you are executing an idea, an expression, a feeling, then you are creating art,” she says.

McCreanor makes her art gallery debut in Triennial with Hydraulic Press Girl and Smac vs. EMOJI – comedic videos that were launched on social media. Vision of McCreanor imitating the compression of objects under a hydraulic press for the former has accumulated more than one billion views online.

“My work always comes from a place of enjoyment first – if I’m amused by the idea, then I do it,” she says. “It’s a bonus if it’s well received by others.”

Japanese flower artist Azuma Makoto considers art to be a “deeply spiritual and sensory experience (that) each person interprets and receives in their own way”.

“(Art) is open to interpretation, and there is no right or wrong answer as to how it should be understood,” he says.

Art “definitely enriches people’s lives”, adds Makoto, who is best known for pushing the boundaries of art by launching plants into the stratosphere and into the deep sea.

“Art serves as a means to raise questions, stimulate thoughts, and awaken people’s hearts,” he says. “Forms such as music, painting, sculpture, fashion and design are universal languages that connect people, even in today’s increasingly divided world.”

Agnieszka Pilat – a Poland-born, New York-based artist whose craft has evolved from classical painting to working with robotics — considers art to be “a skilfully expressed message embedded in a medium that sparks important conversations about universal issues”.

“It should embody ‘newness’ – that’s the creative part – and innovation, and must stand the test of time, while being situated in the context of art history and the history of humankind,” she says.

For Berlin-based duo Elmgreen & Dragset, aka Michael Elmgreen and Ingar Dragset, “anything made by an artist that is exhibited as art is art”.

But the pair – renowned for installing fake luxury store Prada Marfa in the Texan desert, and a pool shaped like van Gogh’s ear outside New York’s Rockefeller building – says “to label something ‘art’ is not a quality stamp in itself”.

“There is good art and art that is not as good, and the field of visual art is constantly expanding,” they say.

“Lately, we’ve experienced a boom in digital and robotic art, but that doesn’t mean that more classic media, such as figurative sculpture, is any less relevant.

“It comes down to what the artwork has to tell us, if (it) moves us, makes us reflect, or upsets us in any way.”

The DNA of art

Developing an artwork starts with an intention to “express or communicate something”, requires originality and creativity to come to life, and should trigger an emotional response, McEoin says.

Unlike Gander, the NGV curator is comfortable with an artist’s intention being “purely aesthetic”.

“It may also be about an artist communicating an aspect of their life (or) trying to tell a story about the world around them,” he says. “It could be setting out to make money – a lot of money moves around the world in the buying and selling of art, which has a net benefit for society. Intentions (behind art) are very broad.”

As are the emotions an artwork can evoke. “Someone could appreciate its beauty. It could move someone, change their mind, provoke them, upset them. Humour is also a valid response,” McEoin says.

“But it would be very hard for an artwork to be world famous if people stand in front of it and feel nothing.”

From Indigenous cultures using early forms of art to “locate themselves within the universe”, art evolved to a point where it was all but controlled by power structures – like religious institutions and monarchies that recognised its ability to “capture people’s imaginations, evoke an emotional response (and) shape people’s thoughts”.

Then, McEoin says, “in the 20th century, we start to see artists freeing themselves from the constraints of producing art for other people, to start producing art as self-expression”.

“That’s where we think about contemporary art (beginning as a period),” he says. “But when we talk about contemporary art, it’s important to point out any work is contemporary to the period it’s made in.”

It goes without saying that the artist is a key player in the creation of art – but so is the viewer. Their role is to experience the emotional response McEoin has discussed, and to interpret the piece.

McEoin concedes the latter responsibility can be intimidating for many people, but says any interpretation of an artwork is valid.

“I think people have been taught to believe there’s some secret language that artists are trying to operate in, or it’s elitist,” he says.

“Sometimes an artist might intend for an artwork to have a certain role. But once you put it in the world, you can’t controlhow people interpret things. That’s part of the excitement.”

Gander encourages people to “take away what they want” from his Triennial artwork, The end, comprising a tiny animatronic mouse that has burst through a wall to “deliver a 15-minute sort of prophecy” voiced by Gander’s young daughter. “There’s nothing that I expect them to take away,” he says.

“I just hope it is endearing enough or confusing enough, or cute enough … to intrigue people to listen to her story.”

Gander views art as a “healthy distraction” for humans who are, “in general, desperately looking for a distraction”. Engaging with art is a “great way to exercise your mind”.

“Museums are a bit like going to the gym,” he says.

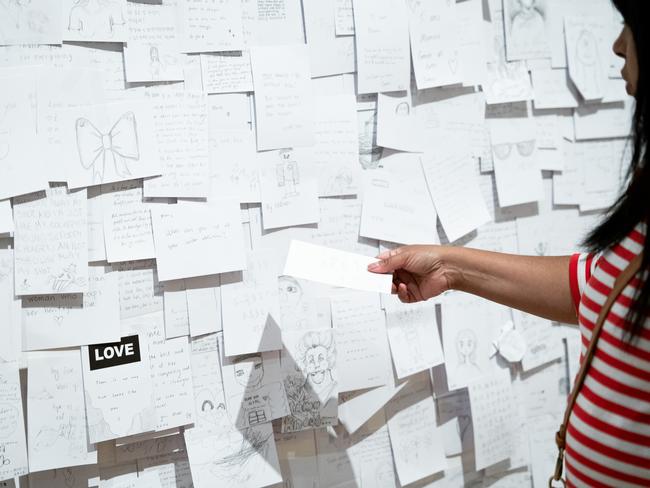

The role of the audience is more literal in two other Triennial works: Yoko Ono’s My Mommy is Beautiful and David Shrigley’s temporary exhibit, Melbourne Tennis Ball Exchange.

Of the latter – which asked people to bring a tennis ball to the NGV and swap it for a new one from a wall of more than 8000 balls – Shrigley says: “The work is created by the people who interact with it.”

Ono’s piece similarly invites visitors to write their reflections about their mothers on pieces of paper and pin them to the wall. McEoin says it has been one of Triennial’s most emotionally impactful experiences.

“Yoko’s artwork opens up the space for us emotionally, where we can spend time reflecting on our relationship with our mothers,” he says.

“If no one left a note, we’d just have an empty room. It’s a reminder that we all need to make a contribution to shape the world in a positive way.”

Art must keep evolving

Traditionalists wedded to the idea that “art is a square on the wall” may scoff at Triennial’s more boundary-pushing works.

But the world’s pre-eminent creatives agree that evolution is inevitable, and crucial to the future of art.

“If nothing were to change beyond our control, we would be bored to death,” Elmgreen & Dragset say. “There would be no surprises.”

Makoto agrees: “Art will continue to evolve as long as humans exist, but it is also necessary for the richness of people’s hearts to deepen in response to it.”

Gander similarly hopes people will “embrace (art as) it becomes more complex” and not “find it elitist”.

McCreanor adds the creative sector “feels limitless and powerful”, but still capable of “acknowledging and respecting traditional art”.

To detractors of her work, she says: “Emojis have had a huge impact on society. With almost everybody immediately being able to resonate with them, I’d say they’re an icon in pop culture, which is always relevant in the art world.

“I’m honoured and humoured that it’s in a gallery.”

To explain why art must progress, Pilat points to the opera.

“It’s such a beautiful form of art, but because there’s been so little innovation, it’s very hard to get young people to see it,” she says. “Artists need to innovate because they need to connect to the contemporaries and if you keep on doing the same thing, it’s hard to connect.”

Pilat personifies the progression of art – she was “a figurative painter with a strong realist foundation” before teaming up with robotics company Boston Dynamics to train AI-enabled robot dogs to paint for her Triennial exhibit, Heterobota.

“Working with robots is a logical and inevitable result of my evolution as an artist,” she says. “If artists ignore one of the most significant shifts in human civilisation – the massive move towards autonomous technologies that will change how we live and evolve – we risk rendering ourselves irrelevant.”

Whether “artificial intelligence will take over the world of art” has recently been the subject of “chatter” in the sector, McEoin says.

“It’s quite exciting what artists can do with it,” he says. “But I don’t see anything of any great merit being produced once the human element is removed.”

Pilat’s Heterobota is an example of “a very important artwork” that uses AI, McEoin says: “It’s less about what (the robots) are painting, but more about asking us to consider … that we live in a world where robots and AI are increasingly part of our industries and our lives.

“Pilat is asking us, ‘if we’re creating these things, do we care about them?’ She’s also reminding us that … at some point, (robots) may need to have their own freedom to express themselves.”

Pilat says she wants to “evoke positive emotions towards the robots”. She also hopes their paintings will trigger “a new era in art-making”.

“If technology progresses … it’s possible and even likely we will have semi-intelligent, semi-sentient artificial intelligence machines,” she says.

“My dream is for them to come to a museum and look at the paintings, say 500 years from now, in the way humans look at ancient paintings and try to figure out, ‘What were they communicating? Are these our ancestors?’

“Art is a conversation that transcends space and time.”