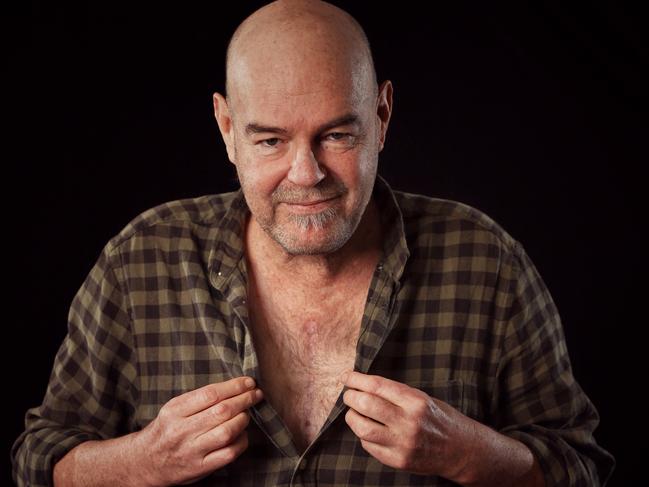

VWeekend: Mark ‘Robbo’ Robinson’s secret health battle and heart surgery

“At 54, I had driven my body into a wall. Mangled it.” Mark Robinson reveals how he ignored his health, until he faced death.

Lifestyle

Don't miss out on the headlines from Lifestyle. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Breathe. Breathe. Breathe.

I can’t get air in.

It’s dark, about 5.30am, and I am sitting on my bed, feet on the floor and wondering what the f--k is happening.

My chest is aching because of the tight lungs and my breathing is short. A Gatling gun of 20-25 breaths every 10 seconds. I’m panicking and no matter how hard I gulp, the air gets stuck in the back of the throat and coughs itself up.

My arms cradle and then clench my chest. The pain is a powerful stitch across the upper body. In one area, then another.

I am cold. And I can’t breathe.

I sit there hostage to this phenomenon invading my body. Ten minutes? Half an hour? Eventually the breathing deepens and I lie down again and fall asleep.

When I wake up, around 9am, I feel sh--house. Listless and beaten.

I figure I have Covid-19. I’d seen the TV adverts the night before, while watching Richmond beat Brisbane in Round 18. They were interspersed but never as plentiful as the adverts for fast food and from gambling houses.

Still, my concern is the breathing and the pain.

I have been a smoker for 35 years so, internally, it’s inevitable that my number would come up for Covid. My immunity levels are feeble. These past few years, I would pick up a chest infection opening the freezer, and cough it up almost nightly next to Gerard on AFL360.

Anyway, the plan was to stay home Saturday – skip my daily lockdown adventure of visiting Warrandyte IGA – and submit to my customary working weekend covering the football without having to see anyone in person.

I would visit the doc on Monday morning for a Covid test.

So, I tune into Crunch Time at 11am, 3AW at midday, Countdown on Fox Footy at the same time, watch the Saturday triple-header and close the night out with a chat to Corey from Champion Data, with Lewy, Kath and Johnno chatting on the box in the background.

I sleep OK and wake up Sunday fresher and from 9-ish, start writing The Tackle column for the Herald Sun, do 3AW from midday, and then buckle in for a four-game Sunday slog. File. Update. File. Update.

About 9.30pm, with the first edition of the Herald Sun put to bed and the metro edition updated, I feel demolished and hit the sack.

It’s lighter this time. A dark grey lights the gap between the wall and curtains. Maybe it’s 6.15am.

I am sitting up on the bed, my feet on the floor and – whoof, whoof, whoof – I’m gasping for breath again. This time it’s worse. Panic is now fear. The intensity of whatever is hijacking my upper body is not computing.

Will it stop? How can it stop?

The breathing returns to normal after who knows how long and I’m not sure whether I fall back asleep.

The awareness of time vanishes. The awareness of being cold is crippling. I am going to hospital, I know it.

It’s crazy how the mind works. I shower and put on clean underwear, because that’s what mum always said to do when you’re going to hospital.

I feed the dogs, with an extra raw egg on top, hug them and put them out.

I turn off the outside pond filter so the fish won’t be sucked into a certain death if I am away too long.

I hide house keys outside.

I clean up the kitchen, put out the rubbish and then sit down and light my final cigarette. Two puffs and that is it.

I am shaking, cold and scared and, for the first time, think that I might not be coming home.

The car has just a vapour of petrol so I take the phone, the wallet, the keys and drive to the nearest petrol station.

At the bowser, I think the person who picks up my car from the docs doesn’t need a full tank, so I only put in $20. Two tradies say “hello”, but my reply is a grunt. It was all I could manage.

It is 8.45am and I’m driving back through Warrandyte, beside the river, and to the doctor opposite the footy ground. I’m still cold and still shaking.

I park the car, trudge through the door into the doctors’ foyer, stand there numbly not looking at anyone in particular and say, “I need help”.

And burst into tears.

TRIPLE WHAMMY

It wasn’t Covid. It was two heart attacks. Lucky is a gross understatement.

The outcome was a six-bypass, open-heart surgery.

“You’re one off my record,” my cardiothoracic surgeon Mr Philip Hayward said, estimating I was close to his 2000th heart-bypass patient.

“I’ve put in seven bypasses before and you’re six.”

I didn’t know whether to feel proud or ashamed. Shame won.

At 54, I had driven my body into a wall. Mangled it.

Haphazard diabetes control – I was an “immune-type diabetic” for 15 years – plus laziness, stupidity and gung-ho naivety, combined with a broken work-life balance through the footy seasons at least, and ultimately topped off by a two-year world pandemic – well, my body eventually rebelled.

There’s a hereditary element – my paternal grandmother and a couple of dad’s brothers died of diabetes and on the other side there is history of extensive heart failure – but the living have control of the environment, not the dead.

Mr Hayward – a Londoner who looked at me oddly when I playfully called him Fab Phil ala Phil Carman – is more matter of fact than arm-around-you. In his business, he’s the plumber, not the cuddler.

We talk this day, almost three months post-surgery, because he is free and I was eventually ready to listen – and to go back there mentally.

He said a rare six-bypass operation was manageable because of my age.

“There’s three main coronary arteries and they give off little branches like a tree. The younger the person is the more interested you are in completely bypassing everything that’s blocked. As opposed to a very old person, you just might do the two or three worst ones to get them out of trouble.

“The rationale is old people don’t tolerate long, complex operations as well. You are classed as young, very young.”

There were other major complications. At hospital on Monday, tests showed I had a blood infection. On Tuesday, it was determined I had pneumonia, which is fluid in the lungs.

There was an air of urgency. The heart operation was postponed so drugs could try to kill off the pneumonia and on Thursday Mr Hayward explained the heightened danger involving such serious surgery while carrying pneumonia. In the end, he opened me up on Friday about 2pm.

An artery was taken from each of my arms, having being opened up from the wrist to the elbow on the belly of the arm, and they were halved to make four of the bypasses.

The other artery – the mammary artery – was taken from inside the chest/rib cage and that was used to cover two bypasses.

“I got six bypasses out of three pipes,” Mr Hayward said.

“You had blocked the most important of the three big arteries. It’s called the left-hand artery descending. It’s on the front of the heart, and it used to have a horrible nickname, the Widowmaker.

“After WWII, it was the commonest cause of death in men, so it was called the Widowmaker Silently, you had previously blocked another artery, unknown.’’

So, how did I not die from either heart attack?

I was lucky. Twice. Because blood clots which had formed in the “Widowmaker’’, which caused the breathing issues and the acute pain, were able to be dissolved.

If the artery had remained blocked, I might not be writing this. There’s a real chance I would be dead.

“You had a heart attack and got through it,” Mr Hayward said.

“You were able to dissolve the clot and the flow of blood re-establishes. Two days later, the same thing happened.

“In terms of modern medicine, you wouldn’t expect to die from the coronary blockage you had on Saturday, assuming you went to hospital and sought medical attention. Given you took the old fashioned way – you just ignored it – then you could’ve easily gone the way of the Widowmaker. Untreated, a blocking of that coronary artery, and Melanie Freeman (my cardiologist) can give you a number better than me, has a significant mortality if you ignore it as you did.

“If you ignored your second heart attack on the Monday, then you were in terrible trouble.”

The onset of pneumonia was tricky.

“Obviously the heart attacks made you unwell, but the biggest factor for me is you had quite a bad pneumonia with it, which you developed between the heart attack and the surgery and that is essentially down to three things,” Mr Hayward explained.

“We know that smokers get pneumonia because they clog their lungs, we know diabetics have poor immune systems and you had a very poor diabetic control at the time, and then your lungs were congested with too much blood in them because the heart was pumping weakly because of the heart attack.

“You had a triple whammy … and I think you’re very lucky.”

Dr Freeman agreed.

She was alerted via the ambulance of my condition.

“When you arrived, you had what’s called an ST elevation myocardial infarction (or heart attack), a type of heart attack recognised on the ECG which usually suggests one of the arteries is totally blocked. This type of heart attack can cause a cardiac arrest and some people even die from it,” she said.

“That’s why, when you came in, you were rushed in to do an angiogram.

“You had a very, very, horrible blockage in the main artery; it was 90 per cent blocked. That was the problem. You also had multiple other blockages. And you had pneumonia. And diabetes … the hat-trick.

“Basically, one of the main arteries was totally blocked and the other artery was almost totally blocked. If that had gotten any worse, you wouldn’t be here today.”

The operation took roughly six hours and my heart was stopped for 108 minutes.

I woke up 48 hours later.

LOVED, BUT ALONE

It’s funny, but when you think you might die, or people think you might die, life becomes practically simple and emotionally complex.

The four-and-a-half days in hospital pre-surgery and the 10 days bedridden post-surgery – in a Covid world, where family and friends are denied access and nurses are angels in masks – was wholly confronting and tormenting.

I have never felt so vulnerable and, at times, more alone.

That first Monday is really a blur. After being at Goldfields Medical Centre at 9am, I was at Box Hill Hospital by 9.45. The ambulance trip was navigated amid a frenzy of calls and messages to family and work colleagues – made by the ambo man.

By 11.15, I was having an angiogram, an X-ray procedure which evaluates blockages in the arterial system, mainly for the heart, and that’s when Dr Freeman introduced herself with the news that stents were out and bypasses were in.

Dr Freeman ordered a barrage of tests: Blood was taken, blood pressure was assessed, blood thinning drugs were injected, painkillers the same. There was insulin, aspirin, plenty of stress and staggered sleep. And, surely not another ECG.

The nurses were gloriously efficient – save for the time four of them in order missed a vein in my arm in a bid to extract a sample – and wonderfully responsive to my needs and fears.

And there were many.

Doctors, specialists, nurses, students and interns seemingly surveyed most parts of my body as I lay on my back stunned and useless, looking about at what seemed to be a movie set. It felt unreal.

Eventually, the hellish day ended with a near midnight trip to Knox Private Hospital, again in an ambulance, which brought finality to one of the craziest days of my life.

Then, in the next 12 hours pneumonia arrived. While the body was fighting its battle, the mind was wrestling its own.

When you think you might die, and your closest think the same, the messages of concern and support at first are surprising and then unashamedly overwhelming.

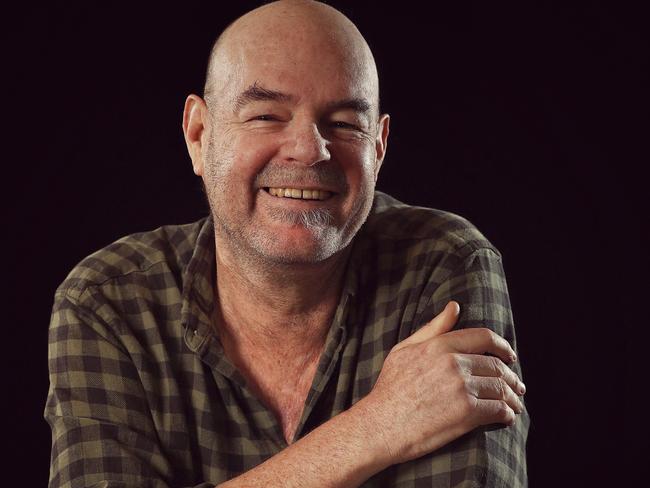

Asked what I learnt through this life-assessing event, the answer is: There’s more love, warmth and care in the world than I ever imagined.

Primary and secondary school friends sent messages, as did some of their parents. Old teachers. Old girlfriends. Work colleagues now and past. Teammates from the three footy clubs I played with. AFL players and coaches and footy staff. People I had written about, quite critically at times, sent two and three text messages.

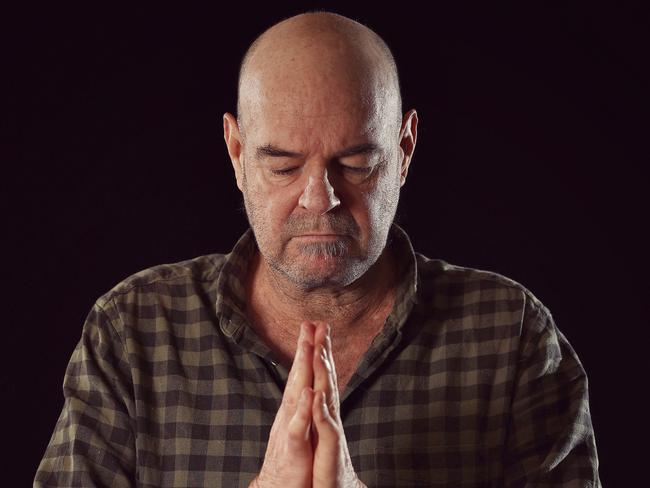

The messages came as word spread of my predicament. The worst time – and it should be incentive enough for anyone to take care of your sugars – was the six hours before my operation on the Friday.

That time was for family and my closest. Text messages and phone calls began with mirth and ended in tears. It’s difficult to write this as I remember my fear and theirs. I’ve told people it was the closest thing to being at your own funeral. Texts were written without the prefix “Just in case you die, I want to tell you …’’. But that didn’t have to be said.

We all knew there was a chance I wasn’t coming back. Still, the texts and calls were sincere and profound and incredibly emotional.

It was about this time I wrote my will. You know, just in case. Trust me, it’s an intense and practical realisation of your mortality when you’re penning an emergency gift bag.

My cousin Mick added humour to the situation – and we needed it. He texted back, saying he had already been at my place and filled his ute.

On the family front, those six hours were the best and worst.

Personally, when the masked angel came in to wheel me from my room to the holding bay, well, I’ve never felt more alone in my life.

I’ve likened the sensation to, I imagine, what it would be like walking up the race as a player at the MCG on Grand Final day. Unfettered nerves amid an odd tranquillity and the one indelible and unanswerable question: What the f--k is going to happen now?

At the holding bay, the pre-meds are injected, which makes the final stretch to theatre a time of merriment and introduction, as one of my videos shows.

The last thing I can remember is being told … just breathe …

I can’t remember when I first woke – it was Sunday at some hour – and if immense loneliness was my last recollection, my new world was one of utter helplessness.

As well as fixing my heart, it felt like Mr Hayward had – just before he clamped my chest bone – swiped all strength and power from my body. I woke in a room inside ICU, not so much scared but lost, and straightaway an angel in a mask was beside me.

My body was a mess, and my mind wasn’t much better, clearly because of the anaesthetics and the painkillers. I was hooked up to machines and my arms had tubes intertwined with more tubes. In some ways I was like a sick newborn baby.

Amazingly, the angels made me walk barely 24 hours later, on a pusher and for 10m. It was important for recovery, they said. Amazing because it wasn’t until day four I could hold my phone. My arms looked like they had been properly filleted, and the scars will be a lifelong reminder.

Slowly, with each passing day the body took a step for the better, and three months on, the body’s ability to recover has astounded me.

My only other football analogy centres on the nurses. By my reading, Mr Hayward and Dr Freeman are the senior coaches of the team. They set strategy without emotion and certainly Mr Hayward is in charge on game day.

The nurses are the assistant coaches. They spend more time with you one-on-one. They help feed and clean you, and they listen and they care.

Night two or three in ICU, I woke in a panic and ripped off my oxygen mask and messed up my arm tubes. A nurse sat with me and held my hand for God knows how long. We told life stories and everything was soothed, soon enough.

The next time I saw her I asked her if she would momentarily unhook the mask from her face so I could see what she looked like.

It was the first smile I had seen in more than a week. It might have seemed more pertinent then than it does now, but those nurses were ports in my storm. Without visitors, they became sort of family.

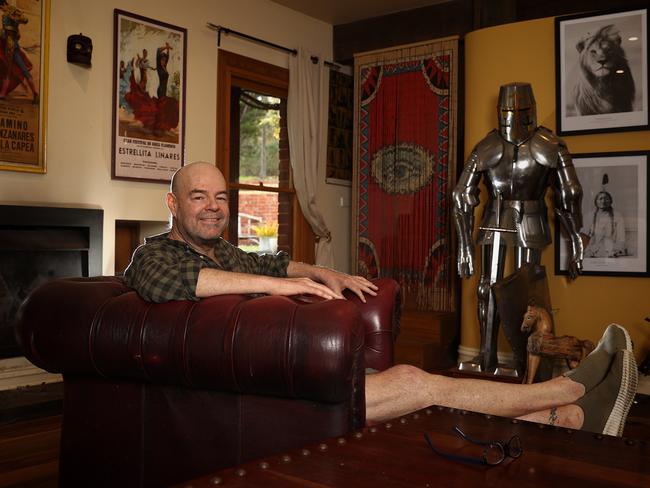

My carer at home was Matt Kitchin, a work mate who asked his wife if he could nurse me back to health. He moved in for seven weeks. He scaled Mount Everest three years ago, so bringing me back to life would be a doddle, surely.

“You never want to see your friend like this,” he said.

“So desperately fragile in the first week and a half, he could hardly walk, and couldn’t hold his plate or cut even soft food.

“He barely spoke that first week. My robust old mate was a broken shell and he looked haunted. Then slowly but surely every day he got a little bit stronger. The mind came back much faster and the body frustratingly had a lot of catching up to do.

“Every milestone was a celebration. Slept through the whole night. Sat up to eat a full breakfast. First rehab session. Walked a minute on the treadmill. The first scotch and dry.

“I’m stoked about his new mindset. Everything in moderation.”

BEWARE THE SILENT KILLER

This is not a sermon for anyone, not even for the people close to me who have forms of diabetes.

It’s a story about a bloke who had haphazard diabetes control and suffered the consequences, which could’ve been avoided if he’d only listened. And acted.

That’s the message.

Because you don’t want to be in hospital after two heart attacks, with pneumonia, with a pen in hand compiling a will, all the while telling people you love them, in the foreboding last hours before surgery.

My God, that time was brutal.

The simple fact is my heart attacks, Mr Hayward said, were because of the sugar in the blood over the past 20 years more than the 35 years of smoking.

“It was once thought heart specialists would go out of business because smoking was on the decline but smoking has been offset by the increase in diabetes,” Mr Hayward said.

“Smoking is on the decline, diabetes is on the rise, sugar is driving obesity, obesity is driving diabetes, diabetes is driving heart disease.

“The other factor is diabetic heart disease is harder to treat than smoking-related heart disease.

“Not only are we seeing just as much heart disease, but the pattern of disease is worse. Smoking caused narrowings at the entrance to vessels but beyond that the vessel wasn’t too bad. Diabetes causes narrowing all along the arteries.

“So, the quality of the bypasses is not as good as it was in smokers because the arteries are more diseased.

“I did make a note with you, we were surprisingly lucky in that the arteries out of your arm, in spite of your diabetes, were actually very clean.

“But that’s not always the case. Sometimes, we are using diseased pipes to bypass diseased vessels.”

Mr Hayward suspects the Covid pandemic will increase heart disease because of a reduction in fitness, drop in activity, poor eating habits and reduced health checks.

“For me, I’m worried that Covid has become such a major distraction in health care and people’s perceptions of health care. As you said, you thought you had Covid and thought you’d wait it out.”

Dr Freeman said people needed to know the warning signs of heart attack.

“Chest pain or breathlessness could be a heart attack and you need to act on it, and not ignore it, and not assume it’s something else like reflux … or Covid.

“You have to live a healthy lifestyle. Obviously smoking is the worst thing you can do for your health. Exercise and good diet is important, and yearly screening for conditions like diabetes, high blood pressure, and cholesterol should be performed at least once a year.”

Similar to many people, every year I do a full blood test. This year it was on June 29. My local doctor rang me back on July 1 and said my sugar levels were high and my cholesterol was slightly high.

Three weeks later I had two heart attacks.

The point is, blood tests don’t tell the full story and in many of us there’s a silent killer – a widowmaker – ready to pounce. And it almost got me.