The 30 most influential Victorians of the past 30 years

They may not be the richest, most powerful, or the most famous, but these are the faces who have made Victoria a better place over three decades through their deeds, careers or changes they’ve championed. As the Herald Sun marks 30 years we celebrate 30 people who have made our state great.

Lifestyle

Don't miss out on the headlines from Lifestyle. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Lists spark debate. They get people talking, and sometimes arguing.

When a list of achievers is published, such as Victoria’s most influential people over the past 30 years, readers often focus as much on who is not on the list as who is.

That’s why the criteria is worth noting. “Influence”, in this case, is contained to the period since the Herald Sun was launched in 1990, which is why Paul Kelly and Kylie Minogue are on the list but Molly Meldrum is not, despite Meldrum’s musical pre-eminence, particularly as Countdown host from 1974 until 1987.

It’s not a list of the richest, or the most powerful, or the most famous. When defining influence, it’s a list of those adjudged to have made Victoria a better place over the past 30 years through their deeds, careers or the changes they’ve championed.

Compiling such a list, drawing on judges from a breadth of industries, was difficult. Robust discussions inspired unexpected talking points.

How do you compare good deeds?

How do you measure scientific breakthroughs against sporting moments, or tangible benefits with feel-good triumphs?

How do you quantify international success, and the sparkle of celebrity, against the largely unrecognised efforts of local contributors? Or this: can a horse qualify as “influential”?

Such questions help explain why we haven’t ranked the top 30.

Some people on the list are household names, others are quiet achievers. Not all were born in Victoria, while some have lived afar for years. But they are united in their sway over the shape, future, understanding for and celebration of Melbourne and Victoria. What they share is an enduring legacy. They are, under the loose categories of sports, science, politics, arts and society, the people who have mattered most to Victoria since 1990.

Some of Australia’s most important people aren’t there, such as Bob Hawke, an SA-born, WA-bred, Victorian PM who left office in 1991 and later called Sydney home. Or Cate Blanchett, who was born and educated in Melbourne but left in the early 1990s to take on the world. Others, too, could be on the list. Walter Mikac, for example, or Jim Stynes, changed us for their resilience in adversity. It’s fair to say that some names on the list double as proxies for the contributions of others.

Working Dog is not as recognised as, say, Kath and Kim. But the breadth of its comedy contribution, including some of the most quoted lines, nudged out two or three celebrated contenders. Some may wonder why Premier Dan Andrews doesn’t feature. He has won two elections, after all, and is confronting the state's greatest health and economic crises. On balance, the judges felt the ALP’s former Premier Steve Bracks — who won three elections, and steered prosperous times — is to date a more significant contributor.

This may change, of course, if the list was to be updated five, 10 or 30 years from now. A future list might include basketballer Ben Simmons or entrepreneur Ruslan Kogan, just two achievers of many who are reshaping the world, our state and our capital city.

SUSAN ALBERTI

Spurred by tragedy and loss, Susan Alberti responded with determination and resolve. Philanthropist, campaigner and role model, the former Western Bulldogs board member led the push for an elite women’s football competition, which would be established in 2017. Her never surrender attitude was forged after her daughter, Danielle, was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes as a child. Alberti has since spearheaded campaigns to raise $30 million for a cure. In 1995, Alberti’s first husband, Angelo, died in a motorbike accident, and she took over the running of 300 staff at their commercial and industrial building business. Six years later, Danielle, at 32, died in Alberti’s arms of kidney-related complications. The Victorian of the Year in 2018 has long spoken out against injustice and discrimination. “The grassroots of the game have also come a long way with one glaring exception - until 2017 we did not have an elite women’s national competition,” Alberti tells the Herald Sun. “We now have (an) AFLW competition which is changing the game for the better by expanding the footprint of our national game, providing a pathway for young girls and women and acknowledging the importance of football being an inclusive, family orientated sport.”

STEPHANIE ALEXANDER

The inspiration for Stephanie Alexander’s The Cook’s Companion was simple. The chef, restaurateur and writer wanted young people to understand how to cook with fresh food daily. With more than 500,000 copies sold, the book grew to be a turn-to Bible for many Australians learning to cook, eat and share, often in Alexander’s favourite pastime of chatting around the table and “debating the problems of the universe over fine wine”. The book, now in its 24th reprint, pre-empted the era of the celebrity chef, much like 1968’s Margaret Fulton Cookbook before it, and tutored a population to relish the joys of dining. Alexander was raised on the Mornington Peninsula and trained to be a librarian. Her mother Mary had instilled treasured food experiences from an early age. A mother of two, Alexander, now 79, ran two prominent restaurants in Melbourne for many years. But the success of The Cook’s Companion “changed my life”. It was so mammoth a task, she now says, she feared she would never finish it. Alexander is particularly proud of her Kitchen Garden program in schools, which teaches children to prune, compost, raise chickens and roll dough, among other things. She hopes to shift generational habits, to reduce the anxiety that non-cooks feel about the kitchen, and to teach that “fresh food is best”. “People become almost paralysed, too scare to start,” she tells the Herald Sun. “But even if it’s a spectacular failure, you learn from it.”

ROSIE BATTY

Rosie Batty stood apart at the funeral of her son, Luke, who had been killed by his father Greg Anderson in an act which numbed the country on February 12, 2014. Mourners sobbed through the service as rain drizzled outside. Yet Batty, resplendent in yellow, projected a resilience that would shift how the country would tackle one of its most insidious secrets. The systemic failures that jeopardised Luke became the spur for her campaign to end domestic violence in the months and years ahead. That same year, she established the Luke Batty Foundation to support women and children. She tackled public perceptions, funding shortfalls, and legal and police processes that had impeded her from protecting her son. Her advocacy was pivotal to the launch of a 2015 royal commission into family violence. Her resolve was recognised when she was made the 2015 Australian of the Year. Then Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull said in 2016 that “cultural change requires a great advocate and Rosie has been able to do that in a way that I think nobody has done before”. Batty herself describes a job unfinished: “We have a deeper understanding of its prevalence. It’s more of a mainstream conversation, where we are less likely to place shame on the victim … but we still have at least one woman a week (nationally) being murdered (by her current or former partner).”

JOHN BERTRAND

The enduring significance of Australia II’s win of the America’s Cup in 1983 was illustrated by swimmer Mack Horton and his Olympic gold medal in 2016. Skipper John Bertrand refused to name his American rival (Liberty) in 1983, inspiring Horton to do the same of Chinese drug cheat Sun Yang. The America’s Cup win became a national obsession in triumph in adversity, to a Men At Work soundtrack, and would embody Australian values of mateship and resilience. The Australian tilt was bedevilled by controversy and officialdom, and looked sunk again and again, especially when the scoreline was 1-3 in the seven-race series, when syndicate owner Alan Bond rewrote the history of World War 1 to declare that an Australian comeback would be “like Gallipoli”. Bertrand, who grew up on the shores of Port Phillip, pursued “sailing perfection”, and has applied his single-mindedness to many roles since 1990s, including as chairman of Australia’s Sporting Hall of Fame, president of Swimming Australia and his long-time mentoring of young people.

Bertrand remembers the day he first met Horton, who presented as shy. “He shook my hand, looking down,” Bertrand says. “I said to him, ‘If you want to become a champion of the world, you have to shake my hand with conviction’.”

Not a day passes without Bertrand being reminded of his historic win: “People want to talk to me about what they were doing all those years ago.”

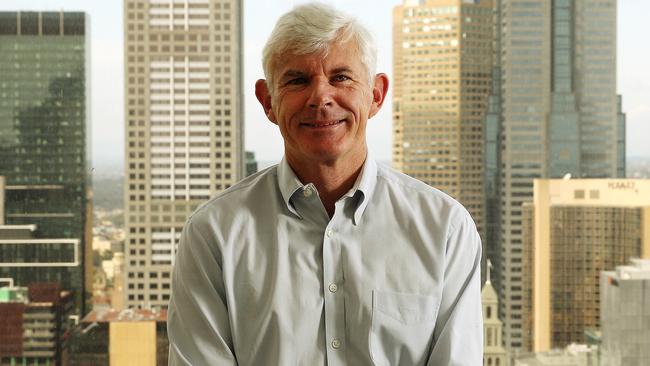

STEVE BRACKS

After Steve Bracks won an “unwinnable” election in 1999, much to his own and the state’s surprise, he was re-elected twice more. Bracks proved to be a salve to the frenetic pace of change under his predecessor, Jeff Kennett, and his understated approach earned him respect from all sides of politics. He was premier for eight years after a savvy political campaign to attract bush votes in 1999 resulted in a hung parliament, and an ALP opportunity to assume power that few believed could be forthcoming – as he says himself now, “I thought we’d just miss”. Bracks lifted spending on health and education, and wound back Kennett government decisions perceived to be overreach. He hosted the 2006 Commonwealth Games, which doubled as a celebration of a confident city which knew its way. When he resigned in 2007, for family reasons, Bracks walked away from politics as a rare thing – a winner. Not that the former Ballarat schoolteacher (who reads Tolstoy classics), felt like it. Speaking of his son’s drink-driving accident, Bracks shared fears common to many parents: “You can’t help feeling a bit of a failure in some ways as a parent,” Bracks said. “You hope and pray and think that your kid is going to do the right thing. You hope that you’ve done enough as a parent.”

In his early 50s, destined to embark on university and not-for-profit board positions, Bracks had no regrets: “I’d like to be remembered as the person who put the heart back into Victoria.”

Melbourne has grown, he now says, as “one of the world’s most liveable cities with its preserved parks and sporting precincts”, in part he hopes because he helped Victorians to “speak out, to be involved, and to be connected”.

PETER COSTELLO

Widely considered the best Prime Minister the country never had, Australia’s longest-serving treasurer, Peter Costello, was repeatedly hailed for higher office. But, in the ignominy of the Coalition’s defeat in 2007, Costello walked away from politics. The Higgins MP – following the likes of prime ministers Harold Holt and John Gorton from that seat – recorded 10 surpluses from the 12 budgets he delivered as treasurer. He erased almost $100 billion of federal government debt, in a lengthy era of prosperity marked by low unemployment and interest rates. After the 1998 election, Costello steered the introduction of the then controversial goods and services tax. He later said that he could have won the 2010 election, had he stayed in politics, but chose to go after warning Prime Minister John Howard to resign before the 2007 election whitewash. In lighter moments, Costello performed the macarena dance on TV in 1996, and asked Australians to have more babies in 2002: “Have one for mum, one for dad and one for the country.” Costello, who has since lamented a lack of wit and cleverness in politics, is now the chair of Nine Entertainment.

NEALE DANIHER

Indomitable spirit Neale Daniher has been fighting the “beast” – his nickname for motor neurone disease – since 2014. His legacy will shine long after his death.

Along with Pat Cunningham, and Dr Ian Davis, Daniher established the FightMND campaign, which has raised tens of millions of dollars for research into the incurable disease.

Daniher played 82 games for Essendon. During his tenure as Melbourne coach, he would become known as “The Reverend” for his wise and practical approach, in attributes that would glow after football. Since 2015, the annual Queen’s Birthday game between Melbourne and Collingwood has hosted FightMND’s Big Freeze to raise funds for research. The FightMND blue beanie has now become a ubiquitous feature of football.

Daniher’s example as a father, player and Victorian of the Year sits alongside his tireless work against the disease. He has conceded, laughing, that he never thought a beanie campaign could work.

Hundreds of sufferers now undertake drug trials, and advancing technologies assist in the faster assessment of sufferers.

Daniher has been a regular on walking trails near his eastern suburbs home since the pandemic lockdown. “When we started out we had no idea what community support we would receive but each year the FightMND army continues to grow,” he tells the Herald Sun. “In time, we are confident the funds we raise will lead to treatments and ultimately a cure for MND.”

PETER DOHERTY

Queensland student Peter Doherty wanted to feed the world when he trained as a vet, until he discovered that economics and politics were bigger factors than cows and sheep. Instead, he turned to immunology, which appealed to his love of puzzling out intricate systems. He shared the 1996 Nobel prize for groundbreaking research into how the body’s immune cells protect us from viruses, a field of heightened popular interest since the spread of COVID-19. His work, along with Rolf Zinkernagel, virtually triggered a new field of science, with applications in transplantation and cancer treatments. Their research, dating to 1973, was driven by boundless curiosity rather than the search for a new discovery. The Peter Doherty Institute in Elizabeth St, a University of Melbourne and Royal Melbourne Hospital partnership, in January 2020 became the first lab outside China to grow SARS-COV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, which it shared with the World Health Organisation. The lab has more than 700 staff, and its work was recognised when director Sharon Lewin was crowned Melburnian of the Year in 2014. Doherty, who turns 80 next week, felt Melbourne was the right place, given he had family here and he’d been “dragging my wife” around the world for so long. After winning the Nobel prize, the 1997 Australian of the Year said: “You’ve got to be very persistent and totally absorbed in what you do. You need to have an open mind.”

As for a COVID-19 vaccine? Doherty thinks it will happen, but its effectiveness is the bigger question. Pandemic risks have grown with international travel and the opening up of China. “I think we should treat this as a learning exercise,” he tells the Herald Sun, “to show us where the problems are. It’s a bugger to get completely rid of it.”

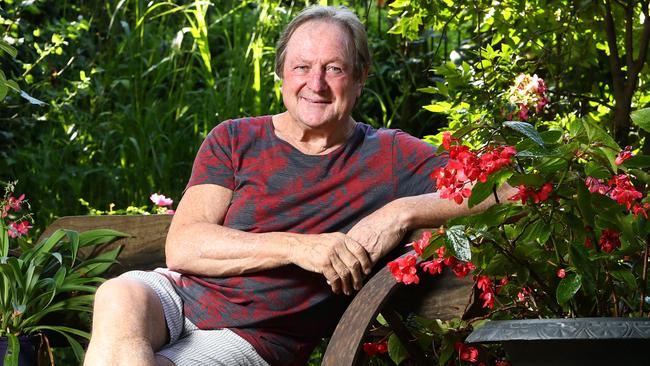

JOHN FARNHAM

It feels like John Farnham has never gone away. After number one records in five consecutive decades, Farnham lives a quiet life in Melbourne’s east, unfettered by social media updates or, indeed, much interest in promoting his life outside of his music. “I live a pretty boring existence really,” he said in 2015. “If I’m not working I go fishing. If I’m not working or fishing I might ride me horse.”

It wasn’t always like this. In the mid-80s, his celebrity dimmed since his days as “Johnny”, Farnham banked his happiness on a new album, Whispering Jack. He suffered panic attacks before its release, but the album became an unstoppable phenomenon, a cradle for anthems such as You’re The Voice, Pressure Down and Reasons, and it was later said that one in three Australian homes had a copy. Farnham’s success has, apart from his voice, been built on his affable style, or what he has called his “inner-dag”. He has released numerous albums since Whispering Jack, and toured with Lionel Richie and Olivia Newton-John.

“I don’t know how to do anything else,” he once told the Herald Sun. “It’s good fun, it’s not brain surgery, it’s just music and entertainment. I love it up there.”

CATHY FREEMAN

Catherine Murch, a Brighton mother, introduced her nine-year-old daughter to her former life not long ago. Her daughter, used to domestic ordinariness, did not grasp that Australia still bows to her mother, also known as Cathy Freeman. Freeman’s 400 metre win at the 2000 Sydney Olympics still inspires every spectator there to try – and mostly fail - to describe the heightened sense of history as she crossed the line at Stadium Australia that night. Perhaps Freeman herself said it best recently: “Where people, for a small moment, became equal.”

Her Cathy Freeman Foundation supports 1600 children to provide paths for experiencing the wider world. Freeman, who moved to Melbourne in 1990, still runs for the joy that takes her back to her childhood in Mackay. But there is one regret. Not the 1990 Auckland Commonwealth Games, when she celebrated victory with both an Australian and Aboriginal flag, and when she said in response to the controversy: “I don’t care, I’m just here to run.”

Instead, she wishes for the slightest deviation to the Olympic night that endures as Australia’s most powerful sporting moment this millennium. Yes, she survived the “beastlike presence” of the crowd that Olympic night. She shouldered the burden of a nation’s hopes. But Freeman still wishes she had run a fraction of a second faster, and beaten 49 seconds.

JULIA GILLARD

Australia’s first female Prime Minister, Julia Gillard, defied the usual conventions for a political career. She herself said that being unmarried, an atheist, and childless were unusual starting points. As Deputy Prime Minister, she overthrew her leader Kevin Rudd in a 2010 coup that abruptly thrust her into leadership. Gillard presented as down-to-earth, a proponent of better education and a Western Bulldogs fan who lived in a humble home in Altona. She formed a minority government in an election held months after she succeeded Rudd, her forced pact with several independents complicating an unprecedented political era. The so-called “gender wars” featured during her time in office which, like Rudd before her, was suddenly ended when she was challenged (by Rudd) for the leadership in 2013. Gillard’s “misogyny speech” of 2012 attracted international attention, and the promotion of women has endured as one of her biggest legacies.

In her farewell speech in 2013, Gillard, who is chair of Beyond Blue, now in its 20th year, said of the preoccupation with her gender: “It doesn’t explain everything, it doesn’t explain nothing, it explains some things.” She tells the Herald Sun: “For me, Victoria is the place that always invites you to take a deeper look. No matter how long you have lived there, you can always turn a corner, take a drive or walk down a laneway and find something new. Victoria’s special sense of community is best exhibited by its unrivalled passion for Australian rules football, which enables incredibly different people to feel a bond. It’s that sense of egalitarianism and inclusion that is enabling Victorians to work together to defeat COVID-19’s second wave. It’s a positive, galvanising force.”

MICHAEL GUDINSKI

Michael Gudinski, or so the story goes, charged Caulfield Cup punters for parking at the vacant block next to his home – when he was seven. Imbued from birth by a need to succeed, Gudinski is considered the father of the Australian music industry, or “Godinski”. He has managed Skyhooks, Split Enz, Kylie Minogue, Paul Kelly and Jimmy Barnes. He has brought Madonna and Guns N’ Roses to Australia. His latest roles, of many, include virtual concerts for upcoming Victorian artists in COVID, and as the organiser of the entertainment for the upcoming AFL grand final in Brisbane. His interlocking businesses, under the Mushroom Group umbrella, have included recording, management, music publishing, film and TV production and merchandise. Gudinski started in music management in the early 1970s, and early struggled for several years, as creative but misplaced ventures threatened to sink his company. Yet he was unstoppable. An observer once described being sucked into “slipstream” of Gudinski’s “hyperbolic enthusiasm”, the attribute perhaps that explains why he is bigger than many of his musical stars. “The problem with the guy is he f------ wants everything,” a Melbourne musician told a journalist in the mid-1990s. “Apart from that he’s doing a lot of good things.”

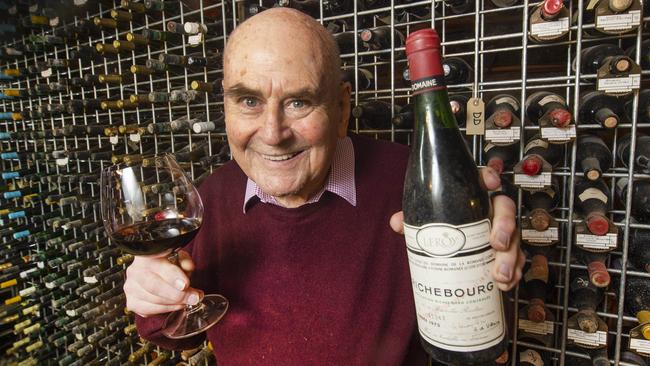

JAMES HALLIDAY

Australia’s most respected wine expert moved to the Yarra Valley in 1985. He had discovered the wine region a decade earlier, which he has called his biggest break, but also his biggest regret because he didn’t find it earlier. Halliday was a Sydney boy whose father, a surgeon, was a wine connoisseur in an era when wine was unfashionable. Halliday was a corporate lawyer for decades, before branching out into wine judging and writing. Sometimes, he tastes 150 wines a day, in judgments, as published in his annual Halliday Wine Companion, which serve as the national benchmark for the industry. The points he awards to a particular wine launches buying sprees and endless talking points. He still lives in a home overlooking the Coldstream Hills winery he founded in 1985. He has described his shift to wine as “a long, slow process of making my mistress (wine) my life”. Now in his 80s, last month, after more than 30 years, in stepped away from running his annual guide (though remaining a panellist), he said: “It’s been a long road with many, many wonderful moments. Always stimulating, always challenging, but it’s time that I step back.”

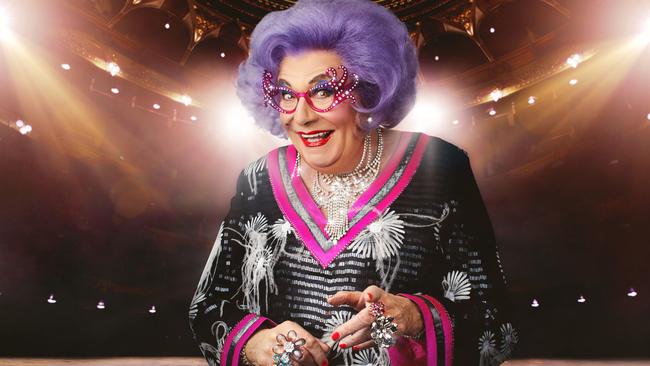

BARRY HUMPHRIES

Barry Humphries is as big on the other side of the world as his home state. Dame Edna, with a little help from Sir Les, launched a superstardom that endures into Humphries’ 87th year. Dame Edna has completed three “final” tours over the past decade as a housewife “gigastar” who distances herself, both on stage and in books, from “the elephant in the room”, Barry Humphries, who invented the gaudy character, as he once said, because he hated her. Humphries has lived in England for many years after he joined the glittering diaspora of Australian, including Germaine Greer and Clive James, who ventured there in the 1950s and ’60s. His international success inspired a biographer to describe him as “the most significant comedian since Charlie Chaplin”, and British newspapers to describe him as a “genius” and the “greatest living comedian in theatre”, though his proudly politically incorrect commentaries have at times riled various interest groups. Yet he and Dame Edna have endured as ambassadors to the world, - making Moonee Ponds a world famous suburb in the process. Humphries is a proud Melburnian who railed against plans to expand Camberwell station, describing the suburb where as a child he dressed in costumes in the backyard, as his “spiritual resting place”.

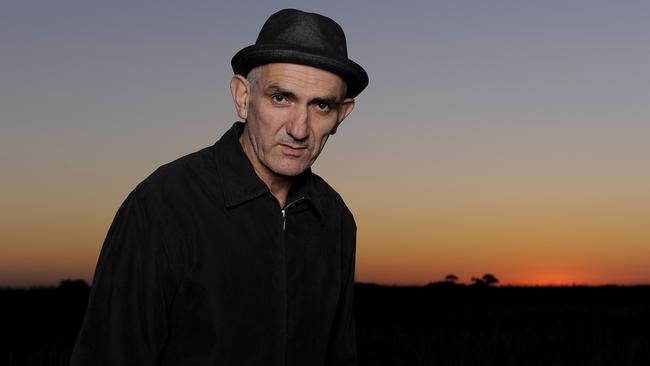

PAUL KELLY

Paul Kelly’s pre-game grand final performance at the 2012 grand final was long overdue. He performed Leaps and Bounds, an unofficial Melbourne anthem, which begins:

“I’m high on the hill

Looking over the bridge

To the M. C. G …”

Kelly, who was born in Adelaide, has been a particularly Melbourne institution since the 1970s. A St Kilda resident, his songwriting about Australian life and culture invites labels of a poet laureate. His private and shy manner belies 40 years in the musical spotlight and 26 albums and counting. David Fricke, of Rolling Stone magazine, once said Kelly was among the best songwriters anywhere. Neil Finn, of Crowded House, said: “There is something unique and powerful about the way Kelly mixes up everyday detail with the big issues of life, death, love and struggle – not a trace of pretence or fakery.”

Kelly’s own hits, such as To Her Door and How To Make Gravy, are complemented by the songs he has written for so many other Australian stars, including “Treaty” by Yothu Yindi. He describes songwriting as a “stumbling process”, as he does life. “There’s only one way to learn: it’s to just make mistakes,” he said in a 2018 interview.

JEFF KENNETT

Over seven years as Victoria’s premier, Jeff Kennett wrenched a parlous state back into the black, with a style and charisma that both attracted and repelled ordinary voters. He represented fiscal responsibility after previous ALP governments had steered the state into the abyss of the late 1980s recession.

Part drill sergeant, part ringmaster, Kennett assumed power in 1992 and set about his “revolution” that same night. He started sacking government department heads and began a rewrite of Victoria’s political, industrial and financial cultures.

He tackled a $32 billion state debt, and a $2.1 billion deficit, as if he was excising a splinter.

“The big decision was made to attack on all fronts at the same time,” Kennett has said. “If we just tried to get the economy right, or correct the health system, all those forces that were opposed to us would have coalesced against us.”

Many Victorians instantly disliked Kennett’s style, which would come to include new words, such as “unVictorian”. They filled city blocks to protest against not just his government’s reforms, but its speed of change.

Since losing office in 1999, Kennett’s commentaries, as well as his voluble role as president of Hawthorn, has ensured his relevance in a city he unabashedly adores. He has been called the de facto opposition leader during the recent virus crisis.

Beyond Blue, Kennett’s advocacy baby after he left politics, has been his biggest legacy, he says. Such work, he argues, was a natural arc for a social liberal who happened to be an economic conservative.

“Beyond Blue lifted the lid on the suppression and ignorance of mental health,” he says. “If someone says now that they are depressed – whether it’s a journalist, chief executive or footballer – they are not victimised. It is a massive social change.”

Kennett continues to confound – and sometimes confuse – both his fans and critics. But his passion for Melbourne goes unchallenged, and he often marvels at the changing skyline that marks the city’s exponential growth and vibrancy.

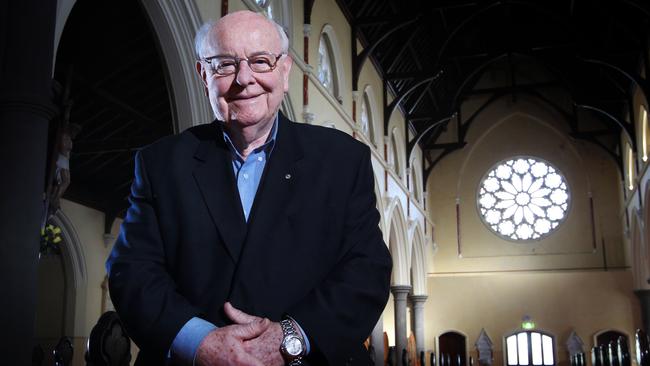

FATHER BOB MAGUIRE

When Father Bob Maguire was forced to retire, aged 77, by the Catholic Church, he likened himself to a fly whose wings and legs had been pulled off. “I’m still a fly, but I can’t fly,” he said. Maguire has long been a popular figure, not only for his extensive charity work, but the values of candour and care in an era when the church slumped in a swamp of paedophilia allegations. His reach acquired celebrity status in the 2000s when he featured on TV, made a rap song, and offered a folksy wisdom, dolloped with humour, which showed he did not take himself or age-old church pieties too seriously. Maguire was Victorian of the Year in 2011, the year before he retired after 39 years as the parish priest of Sts Peter and Paul’s Church in South Melbourne. The Father Bob Maguire Foundation distributes thousands of hot meals each month, (the man himself, into his 80s, would work in soup kitchens most nights) as part of his mission of eradicating homelessness and disadvantage. That the foundation has sold bobble-headed figurines of Maguire (to raise funds) goes to his quirky and embracing nature. His philosophy? “Leave no one behind”. His pillars of wisdom? Compassion and common sense.

EDDIE McGUIRE

Eddie McGuire is the face of two Melbourne institutions, Collingwood Football Club and the long-running Footy Show. His “Everywhere” tag stuck fast since the early 1990s, and McGuire – game show host, breakfast radio host and major backroom player in sport and business – hasn’t slowed since. His ubiquity has raised constant criticisms, but McGuire’s passion for Melbourne goes unchallenged, as evidenced by his long-time committee presence in Melbourne’ major events and tourism initiatives, and his pointed on-air response when a study placed Sydney ahead of Melbourne as a sporting city. In football, according to a 2016 AFL list, he ranked second in the sport’s most influential “movers and shakers” – behind chief executive Gil McLachlan and ahead of Rupert Murdoch, Kerry Stokes and then AFL chairman Mike Fitzpatrick. He adores Melbourne for its seamless blend of arts and football, and nods to historical figures such as John Wren.

His profile extends to charity work and advisory boards, but it is his numerous public platforms, which sets him apart from luminaries of numerous fields, even when his less considered views have received withering criticism. McGuire has avoided going into politics, but it hardly matters to his reach and influence, which could be likened to an iceberg: plain to see but largely hidden from view. Sydney sporting administrator Peter V’landys said recently: “I don’t think the AFL people appreciate (McGuire) as much as they should be because he’s always prepared to go out on a limb.”

He well remembers the first Herald Sun front-page, which depicted Collingwood’s 1990 triumph. “Once we come out of COVID-19, Melbourne has another opportunity to reimagine ourselves,” he says. “We bounced out of the 90s with Victorian major events and set ourselves up. We now have amazing infrastructure, a great city, and the wherewithal to do all these things.”

BRIAN McNAMEE

Brian McNamee fell into leading CSL, one of the world’s biggest vaccine and blood products companies, via medical training – and his love of tennis. He was on a gap year in his early 20s when he descended on Europe to play doubles with his brother Paul. It led to work at a local laboratory in France, and kickstarted a career as one of Australia’s finest chief executives.

McNamee headed the transformation of the Commonwealth Serum Laboratories from a $192 million government utility to a $140 billion (and growing) global giant that went public, diversified products, cornered international markets and multiplied the company share price. With the goal of creating a great Australian company, McNamee headed CSL for 24 years, stepped aside for five years, then rejoined as chairman in October, 2018. CSL has been earmarked for the manufacture of a COVID-19 vaccine, and McNamee has been critical of Melbourne’s lockdowns, arguing that we cannot bank on a vaccine. McNamee was lauded after he led CSL during a critical moment in the company’s growth – from his hospital bed. ”My approach to the remaking of CSL was to address our need to become a globally scaled specialist company … this meant being best in class in all we did and create an environment that could attract and retain great people who embraced this journey,“ he says.

KYLIE MINOGUE

Another of Melbourne’s biggest exports, Kylie Minogue’s childhood career showed few glimpses of the national emblem she would become. It began at Camberwell High School, where she took off days to film her first TV series, and launched worldwide after she landed in Britain in the late 1980s and came to be embraced as one of that country’s own, especially after a tabloid newspaper declared her behind a national treasure. Her catchy tracks (the first international hit, I Should Be So Lucky, was written by London music producers as she waited outside) reached number one in numerous countries through that time, and she is Australia’s the biggest selling female artist. Her enduring significance and first-name-only recognition goes to her powers of reinvention in fashion and music. The world has evolved as Minogue morphed from the “girl next door” with her “bubblegum pop” to a sex siren, accomplished artist and style icon. Minogue’s charity and awareness focus on breast cancer, after she was diagnosed in 2005, has inspired many new non-musical fans. “I’m trying to be myself more and more,” she once said. “The more confidence you have in yourself … the more you realise that this is you, and life isn’t long. So get on with it!”

DAME ELISABETH MURDOCH

Dame Elisabeth Murdoch shied from glamour in life. She spurned the Rolls-Royce her husband Sir Keith once bought. She would not install central heating at her beloved Cruden Farm.

Her state memorial service in 2012 offered some insight into Dame Elisabeth’s reach. Two prime ministers. Five premiers. Four Victorian governors. Three governors-general.

Dame Elisabeth was about getting things done, not about the recognition that goes with getting things done. She charmed and cajoled and once, famously, successfully stared down former premier Henry Bolte.

“Be optimistic - and always think of other people before yourself,” she said in an interview to mark her centenary in 2009.

Her service and philanthropy was marked in the Royal Children’s Hospital and the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute. She was heavily involved in the National Gallery of Victoria, the Victorian Tapestry Workshop, the McClelland Gallery, and countless causes.

Each night, Dame Elisabeth “went to bed with papers and pleas from people”. Each morning at the kitchen table, fountain pen in hand, she would write personal notes to all those who had written to her.

Former premier Jeff Kennett has described Dame Elisabeth as far more than a philanthropist. She gave more than money: she gave of herself. Dame Elisabeth was “always there”, Kennett said.

As her son, Rupert, once said: “Mum has left footprints that stretch across a century, a continent and a society.”

BERT NEWTON

Described by American entertainer Bob Hope as “Australia’s Bob Hope”, Bert Newton’s pre-eminence on Australian TV is unmatched. In a list of Australia’s top 50 stars of TV since 1956, Newton came in first. He has an onstage warmth that embraces viewers of any age, what his once general manager at Channel 10 called his “tremendous adaptability”. “When will I give it away?” Newton said in 2003. “It’s tied in with my passion for the industry … the job itself is the thrill.”

During the same chat, Newton alluded to a Barry Humphries interview in which he described being on stage as being “alone at last”. “That meant a lot to me,” Newton said. “It can be a form of escapism. I handle television better than I handle some aspects of life. When I walk away from television each day, I then have another life that is totally different.”

Newton, 82, has won four Gold Logies. His hosting of the annual event was compulsory viewing. He recycled many gags, some involving hair pieces, but they almost always sounded fresh. Stage plays have kept him busier in more recent years; Newton has always needed to stay busy. “There is a sort of acceptance,” Newton said of his on-air longevity. “Whatever people see in me they also know that I’m quite harmless.”

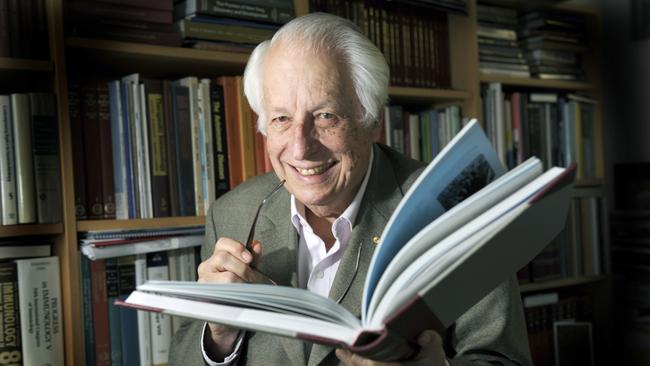

SIR GUSTAV NOSSAL

Science imbued with personality and energy is Sir Gustav Nossal’s gift to immunology and the nation. Nossal headed the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute in Parkville for decades, promoting public health and the development and distribution of vaccines. His work in confirming the theory of antibody formation of his predecessor (and Nobel prize winner) Sir Frank Macfarlane Burnet, was a breakthrough in understanding the immune system.

Nossal, now 89, was once listed among the 50 Australians who mattered to the rest of the world, for his science research and commentary. At one time he was a professor of microbiology, a leader in Aboriginal reconciliation, and a World Health Organisation advisor on immunology. He came to Melbourne aged 26, via Sydney, because he wanted to work under Burnet, who became a mentor. Born in Austria in 1931, Nossal decided to become a doctor at a young age, but was steered to research in part because of poor teachers in his first years at university. He once said that scientific research was “incremental work”, like a pattern or mosaic. He was Australian of the Year in 2000. “The advice that I would give my younger self is – try harder to learn than to shine,” he said in 2018.

JEANNE PRATT

Jeanne Pratt never leaves Melbourne for long – generally, the world, whether it be Nelson Mandela or Muhammad Ali, comes to her. The philanthropist has been a Melbourne fixture for generations, since long before she and departed husband Richard opened Raheen in Kew to regular functions to raise money for charities. She emigrated from Poland in the chaos of World War II, and she was raised to believe in giving. The Pratt Foundation has donated more than a billion dollars to countless causes from the arts to mental health to education. A keen Carlton fan and board member, Pratt calls football a community leveller. Since the death of Richard Pratt in 2009, and son Anthony took over as executive chairman, Visy has more than doubled the size of its international recycling operations. Anthony Pratt has says that Bill Gates, the world’s best known philanthropist, taught him to look past the size of a donation to consider how it might be strategically applied. Now in her 80s, Jeanne Pratt once said she was an ordinary person who has had an extraordinary life.

KEVIN SHEEDY

Exuberance oozed from Kevin Sheedy after his Bombers beat the West Coast Eagles in a 1993 game. He waved his Essendon jacket, in a scene that would be replicated – by fans of the winning side – whenever the two teams have since met.

The moment encapsulated a career loaded with passion, quirkiness and understanding that continues to shine more than a half a century after Sheedy first played as a player. His statistics denote conventional measures of success. He won three flags as a Richmond player, then four as an Essendon coach. But it’s how he did it, as much as what he has achieved. What other personality, for example, has prompted fans, as North Melbourne supporters did in 1998, to throw marshmallows at them? Sheedy has been an innovator of the game who transcended its shifting status from suburban Saturday league to national juggernaut. He conceived of the annual Anzac Day clash between Essendon and Collingwood, has long promoted Aboriginal players in the game, and helped introduce the Dreamtime game from 2007. He thinks of going to the footy as another learning experience for children outside of school. Sheedy’s enduring influence was reiterated when he was appointed to the Essendon board in September.

At 72, he isn’t finished. Sheedy wants the custodians of the game to look ahead, to 2030 and 2040, to prepare the sport for the long-term. About 10 or so rules need to be looked at, he says, instead of being patched with “band-aid” solutions. “The Shrine is the church, and the MCG is the stage, and the Botanical Gardens is our nature,” Sheedy says. Always thinking, he muses about the notion of an island in Port Phillip, so that more people could live on the water, and Melbourne could be even greater than it is.

RON WALKER

Best known for the Formula One Grand Prix, Ron Walker was dedicated to bringing major events to a city known for its blockbuster sporting and arts calendar.

After being appointed head of Melbourne’s Major Events Company in 1991, Walker snared the Grand Prix a few years later when SA’s Premier John Bannon was tossed out of office. Victoria and Walker pinched the Grand Prix before SA knew it was gone.

“Nobody in the world has got as many major events as we have,” Walker said in 2015, three years before his death at 78. “We’ve built an industry in an honorary capacity out of nothing. All of these events have brought in a lot of money, and it will continue. I know to this day that Sydney would probably carve up Sydney Harbour to get the Grand Prix at The Rocks.”

As a 1990s Crown Casino owner, Walker would collect empty beer glasses, like a busboy who forgot he was a property tycoon. As Australian Grand Prix Corporation chairman, Walker always knew the corporate food would be perfect — he taste-tested it himself.

The 2006 Commonwealth Games was his proudest achievement, for their smooth grandness.

Walker treated the fight against a melanoma on his forehead as a “business project” after being diagnosed with cancer in 2011. He leapt at trials of an immunotherapy drug, known as Keytruda, in Los Angeles. Within a few months, the tumours in his lungs, brain and adrenal glands had shrunk by 90 per cent.

Walker wanted others to share in his good fortune. His campaign drew on his network, one of the best in the country. Prime Minister Tony Abbott was called upon, as were many others, and Walker succeeded in having Keytruda approved.

“I have people ring me all the time who are dying, who don’t have access to the drug,” he said on retiring from the Australian Grand Prix Corporation in 2015. “I’m very sympathetic and very determined that this drug will be approved so that people can buy it at a reasonable price and it won’t send them broke.”

SHANE WARNE

Bayside kid Shane Warne wanted to play footy for St Kilda – instead, he revolutionised cricket with a verve that warranted inclusion in Wisden’s five cricketers of the century. He arrived at international cricket level with the so-called “Ball of the Century” to dismiss Mike Gatting in the 1993 Ashes series. His shrewd on-field talents endeared him to cricket followers around the world, and his off-field flamboyance framed him as a household name, if not always for the best of reasons. His hair splashed blond, as if to say “look at me”, he is both the imp he once was and the Inc. he hopes to be.

His breadth is unprecedented: poker tournaments, perfume ranges, ownership in cricket clubs. Warne loves his home town. As he said in a 2017 tweet: “Always love coming back to this amazing city, just the best place in Earth is Melbourne.”

MARILYN WARREN

The first female chief justice in Australia, Marilyn Warren sought to wrench a 19th century environment, as she described the courtroom, into the 21st century. She ended the wearing of wigs in 2016 and embraced technological change to ease the accessibility of the justice system. When she started in law in the 1970s, Warren observed a “sea of men in grey suits”, and corridors clouded with smoke. When she was appointed as chief justice in 2003, she tempered the symbolism of a woman’s rise by pointing out that performance was what mattered most. So she took a deep breath, she later said, and “backed” her judgment. Warren described a “quite momentous” scene in 2015, when she sat with two female justices in the Court of Appeal, with women counsel before them. In 2017, she threatened to charge three federal government ministers for their inflammatory comments about a current case, prompting them to apologise. Warren often rode to work, despite having a provided chauffeur, and she was known for her fondness for loudly playing Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture. If you worry too much about the risks, she once said, you won’t change anything.

LLOYD WILLIAMS

Obsessed by winning a Melbourne Cup since he was eight, racehorse owner Lloyd Williams started throwing tens of millions of dollars into the quest more than a decade ago. It has paid off – he now boasts six Cup wins, more than any other owner in history – although his accountants might wonder at the balance sheets. The founding owner of Crown Casino, and long-time property tycoon, Williams first won a Cup in 1981 with an unlikely winner, Just A Dash, followed by What A Nuisance (1985). His efforts heightened after he purchased Macedon Lodge north of Melbourne (on 120ha and featuring a 75m swimming pool for horses) in 2007 for $5.5 million. That year’s Cup was won by Williams’ Efficient. Green Moon followed in 2012, then Almandin (2016) and Rekindling (2017), when Williams owned more than a quarter of the horses in the field. After that win, Williams, now 80, declared that he would seek to pass trainer Bart Cummings’ record of 12 Cups, assuming he could live to be 115. He has lobbied the Prime Minister to make the Melbourne Cup a national holiday, and often speaks of being a “proud Melburnian”.

“My earliest recollection at school is of being allowed to listen to the Melbourne Cup, and from those very early days the Melbourne Cup became aspirational for me,” he says. “I believe The Cup is the heart of the city.”

WORKING DOG

The founders of Working Dog Productions had been making Australians laugh for years before actors Santo Cilauro, Rob Sitch, Jane Kennedy and Tom Gleisner, along with producer Michael Hirsh, set up a television and film company in 1993. Started at the University of Melbourne, the comedians presented The D-Generation, then The Late Show, in origins hinting of their enduring clout. The tale of how they once improvised, with a borrowed camcorder and props for a skit in the Channel 9 carpark, goes to their innovation and creativity. The mythical current affairs show, Frontline, was uncomfortably close to the truth in depicting cynical journalists who compromised on ethics and truth in pandering to the dog whistle politics of its viewers. The Hollowmen and later Utopia depicted the dysfunctional workings of politics and the bureaucracy. “Straight out of Utopia” is a common catchphrase for real-life government bungling. In between, Working Dog made movies, such as the iconic The Castle and The Dish, which gently parodied ordinary Australians in extraordinary circumstances, and introduced new lines, such as “It’s the vibe” to the everyday vernacular. TV staples, such as The Panel and Have You Been Paying Attention? illustrate how rarely Working Dog misses its marks. “These shows are a little echo of how Rob and Tom and Jane and I started off in the early days of Working Dog and The Late Show,” Cilauro told the Herald Sun in 2015. “We were all friends before we were professional partners. We shared the same sense of humour and enjoyed making the same types of jokes . . . whatever jokes we make (on television) we’d be making (to each other anyway).”

READ MORE:

YOUNG GUNS: VICTORIA’S MOST SUCCESSFUL ENTREPRENEURS UNDER 40