Sticks and stones may break bones, but names are killing our kids

Name-calling is what killed 14-year-old Amanda Grennan in 2017, leaving her mother in a living nightmare every parent fears. Now her mum is speaking out in the hopes of saving lives, saying more needs to be done because bullying is killing our kids.

Lifestyle

Don't miss out on the headlines from Lifestyle. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Sticks and stones may break my bones, but names will never hurt me — but names are killing our children.

They killed Amanda Grennan on August 10, 2017, leaving Deb Langshaw in a living nightmare every parent fears.

She lost the light of her life, her beautiful daughter, to suicide just over two years ago.

Grennan had just turned 14 when she took her own life after vicious and relentless online bullying.

All Langshaw has left now are the precious memories and belongings of a life gone way too soon. The teen’s ashes sit in a wooden box in the lounge room surrounded by treasured photos, candles and her childhood belongings.

Amanda will forever be 14.

She won’t get to have the glam 16th birthday party her mum was so keen to organise with make-up and nails. She won’t have an 18th or a 21st, and she won’t get to marry or ever be a mum.

Her senseless death has left a gaping hole in the lives of those who loved her and as the days go by and start to turn into years, it doesn’t get easier.

“Of course, you learn to live again,” the Cobram nurse says.

“Sometimes you smile and sometimes you laugh, but there’s not one single moment that goes by that Amanda is not in my thoughts.

“I will spend the rest of my days thinking about all the milestones she’s missing and always missing her.

“Amanda was alive, she lived, and I speak about her every day. She mattered and I don’t want her to be forgotten.

“I’ve had people say to me Amanda is now in a better place, but she’s not. She should be here with me. She should have just celebrated her 16th birthday. How can it be that death can become a better place than living in the minds of our children?”

Grennan loved chicken nuggets and animals, especially ducks. She was crafty, organised and an avid list writer.

She was kind and gentle, and always had empathy for others.

Her friends remember her as someone who was always there for them. She organised a birthday party for a young friend who had a troubled home life; her party list had everything ticked off including presents, balloons and breakfast.

She shared a close relationship with her mum and told her she loved her often.

Amanda was also close to her dad, Scott, and brother Shaun.

“Even though Scott and I had separated, we always remained on good terms and Amanda saw her dad regularly,” Langshaw, 48, says.

“Shaun never called her Amanda. From the moment she was born, he always called her ‘my little girl’.”

Shaun recently turned 21 but was unable to celebrate the milestone without his sister by his side.

Amanda could have spoken to any one of her family members or her friends about what was happening to her, but instead chose to keep the extent of her bullying largely to herself.

Three girls targeted Amanda after a broken relationship with a boy — and they taunted her, mercilessly.

They told her she was fat, that they wished she was dead and that she was a waste of space.

Grennan once commented to her friends: ‘‘I don’t drink enough water to cry this many tears.”

The Year 8 student had deleted many of the cruel messages she received day and night for months on end, but when police returned her phone and laptop six weeks after her death to her mother, Langshaw was horrified at the messages they’d been able to recover.

“It shocked me then and it still shocks me now when I see what those kids wrote,” Langshaw says.

“There’s no filter and they were so cruel. Society needs kind and caring people like Amanda and these are the people we’re losing through suicide; the kind and empathetic kids.”

One of the last messages Grennan received was from a parent of one of the girls, who had also contributed to the bullying.

“I can now understand why Amanda didn’t tell me … I know she wouldn’t have wanted me to make a fuss, but Amanda isn’t here now and I’ll keep banging on the door until they hear me,” Langshaw says.

She’s adamant she’s not after revenge and she acknowledges it’s hard because essentially these bullies are children themselves, but she says doing nothing doesn’t help either.

‘‘It’s not bullying — it’s assault and abuse, stalking, and it’s costing our children their lives,” she says.

“There needs to be consequences, especially if these bullies are repeat offenders, and we need to get empathy back into our kids, even if it has to be taught in school.

“It’s killing our children — it killed my child — and something needs to be put in place as a deterrent.”

In December 2017, Langshaw received a letter from the Coroner stating her daughter’s death was suicide as a result of bullying. The letter mentioned the three girls but that was all.

Langshaw requested further investigation, but received another letter saying the same thing.

It made her feel like Grennan's death had been brushed aside — another teenage suicide statistic.

“Amanda might not have been famous but she would’ve been a kind and caring adult who would have made a difference in this world,” Langshaw says.

“She mattered and I won’t ever let her be forgotten.”

Langshaw firmly believes politicians need to talk to the parents of the deceased, along with children and the Department of Education and Training to share ideas and suggestions.

She commends a Victorian Government initiative whereby all students at state primary and secondary schools will be required to turn off their mobile phones and store them during the school day from term one next year.

But more needs to be done educating children on the consequences of their actions.

Langshaw would love to see some sort of compulsory program implemented in schools on the effects of bullying on mental health and is also considering the idea of talking in schools herself.

“If this could help save just one young person’s life, then it’s worth it,” she says.

Langshaw has now had more than two years to reflect on the loss of her daughter.

The memory of their last night together still haunts her.

She’d taken the teen’s phone away but she still had her laptop in her room.

“I tucked her into bed and told her I loved her to the moon and back, and for some reason I told her if anything happened to her it would kill me — she just looked at me and said, ‘I know, Mum, you don’t need to go on’.”

MORE READING:

HOW THREE SURVIVORS STARED DOWN DEATH

PARENTS FEAR FOR KIDS’ ONLINE SAFETY

KID’S USE OF DIGITAL DEVICES PROBED IN WORLD-FIRST STUDY

The next day, Langshaw was at work when she received a phone call from the school asking where Amanda was.

Langshaw raced home, fear increasing by the second.

She didn’t know what she would find behind the closed door of her daughter’s bedroom but every single instinct in her body was screaming in panic.

Amanda was lying in her bed unresponsive.

On reflection, Langshaw says if she could do things differently, she wouldn’t have been so protective of the teen’s privacy.

“There’d be no phones in the bedroom or bathroom, and (devices would) have to be charged overnight in the kitchen,” she says.

“I just went along with society and didn’t give it a thought.

“I bought her a phone for her own safety because I do shift work as a nurse, and ironically it’s what killed her.”

Langshaw was a guest speaker in March for charity Bully Zero Australia Foundation’s National Day of Action against Bullying and Violence.

She shrugs off the ‘You’re so brave’, ‘You’re so strong’ and ‘I don’t know how you do it’ comments she regularly receives.

“I’m none of these things,” she says.

“I’m just Amanda’s mum and I don’t want her death to be in vain.”

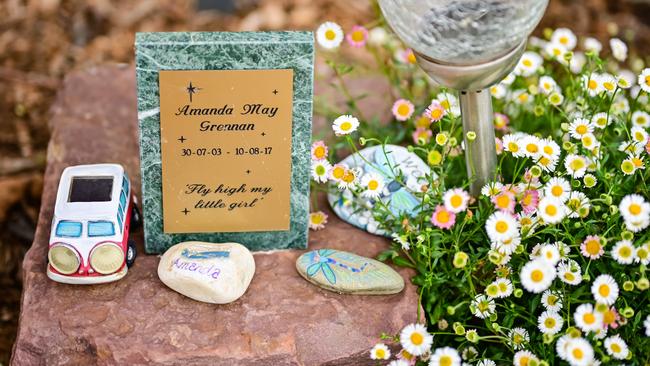

Langshaw has also established a memorial garden in honour of her daughter, which is open to anyone in the Cobram community looking for a place to sit and reflect.

It’s full of little things the schoolgirl loved, including a pile of sea shells she brought home from a beach holiday.

There’s an aviary for Amanda’s much-loved birds, wind chimes tinkling in the breeze and blue wrens that endlessly flit about the roses and other flowers.

There are six “Amanda” roses waiting to bloom and Langshaw says the garden is where she now feels most at peace.

“This garden has bought me back from the brink many times,” she explains.

“I can feel Amanda here and when I’m feeling particularly bad, I come over here with my weed bucket and shovel and just potter.

“People come around and sit, including her school friends, and sometimes I look around and there might be something new that someone has dropped off.”

Langshaw knows she will spend the rest of her life missing her girl, but she hopes that sharing her story might stop another family from going through the torture of losing a child.

‘‘I’ve checked everything a million times and I never found a note.

‘‘I never got a final ‘I love you’ because I always cleared all the messages on my phone and I have nothing.

“I just wish I had saved her messages. I just wish I had her.’’

FOR INFORMATION OR HELP ABOUT CYBER-BULLYING OR BULLYING IN GENERAL:

VISIT AU.REACHOUT.COM OR BULLYZERO.ORG.AU

CONTACT KIDS HELPLINE ON 1800 551 800 OR KIDSHELPLINE.COM.AU

LIFELINE ON 131 114 OR LIFELINE.ORG.AU

BULLYING: THE STATS

● Of 1000 participants aged 14-25 surveyed in 2017 by youth mental health organisation ReachOut, 23 per cent had experienced bullying in the past year. Of those, 52 per cent experienced bullying at school, 25.3 per cent in the workplace and 25.3 per cent online.

● Only half sought help or support for their experiences of bullying. Of those, 48 per cent turned to parents, 33 per cent to friends, 28.7 per cent to a doctor or GP, and 24 per cent to teachers.

● The main reasons for not seeking support were stigma, embarrassment, fear of being seen as weak, feeling they could handle it on their own, and a perception the problem wasn’t serious enough to seek help.

● Frequent school bullying was highest among Year 5 (32 per cent) students and Year 8s (29 per cent).

● Eighty-three per cent of students who bully others online also bully others in person, while 84 per cent of students who were bullied online were also bullied in person.

Sources: ReachOut and Bully Zero Australia Foundation