Back from the brink: How these survivors stared down death and won

These three Melburnians came close to the end in three very different ways. Here’s how these survivors stared death in the face and came out swinging.

After coming close to death, these three Melburnians have created a future unrecognisable from the old where every day is now a blessing.

LYNDSEY WILSON

When a doctor told Lyndsey Wilson she had 45 minutes to live, she was too sick to feel anything.

“I was dropping in and out of consciousness,” she says.

“It was later, when I was in intensive care, that I had a meltdown.”

A weekend away in January 2015 turned into the fight of her life for the Frankston legal consultant.

She was living with her husband in Vanuatu when she and a girlfriend took a short break in neighbouring island Espiritu Santo. They were riding a quad bike when they hit a rough patch and Wilson fell off without suffering any injuries other than what seemed to be a bruise on her left leg.

A few days later, once back in Vanuatu, she started vomiting profusely and had a high fever.

“I knew it felt different to food poisoning because I’ve had that before,” she says.

“The doctor was called and my blood pressure was so low that he didn’t even understand how I was conscious. He wanted me to go to a bigger hospital in New Caledonia, but didn’t think I’d make it. Once I told him about the accident, he knew there was an infection there so he decided to do emergency surgery there and then in Port Vila.

“All I remember is seeing the anaesthetist before surgery and the doctor who said I had 45 minutes left to live but then I woke up with doctors all around me.”

Once fully conscious, she was taken by air ambulance to New Caledonia where she was diagnosed with necrotising fasciitis, also known as the flesh-eating disease, where bacteria infects areas of soft tissue, spreading rapidly to surrounding areas of the body.

The mortality rate is 95 per cent.

She stayed in intensive care for 21 days and that’s when the terror struck.

“I completely freaked out at one point when there were multiple vials and drugs coming in and out of me,” Irish-born Wilson, 34, says.

“I was terrified. They had to sedate me. The doctor was trying to explain they were trying to save my leg, which they did. They were all fantastic.”

But once the infection was under control she was moved to the ward where the infection returned so she was transferred to Brisbane where the whole process began again with further surgery to clean and excise the infection and perform skin grafts.

Another three weeks in intensive care followed before she was released and returned home to Vanuatu.

Life was not going to be the same again for Wilson and she left her husband after years of feeling unhappy.

“I left him two days after I returned to Vanuatu and I left him with everything to return to Brisbane, moving to Melbourne soon after,” she says.

“I’ve always been a strong person but I lost my way in my marriage and my illness made me realise that. It helped make me positive and strong again.

“There were three specific things I decided to do — ride horses again because I used to do event jumping, go diving again and finish a marathon.

“I’ve done all three.”

Wilson has been living in Melbourne since November 2015 with her new partner, a lifelong friend from Ireland, who migrated three years ago. She is studying law part-time so she can return to the bar and is training to compete in the Melbourne Marathon next October.

“I was self-conscious of the scars on my leg for a while but last summer I put on my shorts,” she says.

“If people don’t like what they see, they don’t have to look.”

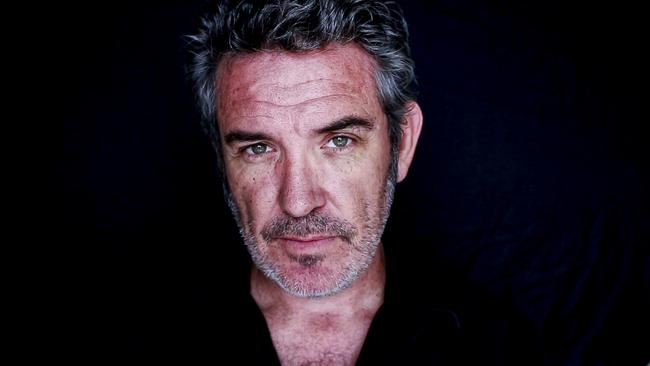

MICHAEL GRAY GRIFFITHS

The man who was so dejected 23 years ago that he didn’t want to be alive is like a stranger to Michael Gray Griffiths now.

Yet it was Griffiths who, at the age of 30, sat in his mother’s car waiting to die.

“I was ashamed of myself, felt that everyone was ashamed of me and I was in a lot of pain so it seemed to be a rational decision,” Griffiths says.

“I thought about it for a while and planned out the whole procedure. I even thought my parents would be expecting it. I was sitting in the car, waiting to leave.”

Griffths was living in Perth when his marriage broke down and then he had a motorcycle accident that caused such extensive damage to his legs that doctors said he’d be left with a permanent disability.

He felt abandoned and worthless.

He was living with his parents, so when they went away he decided to put his suicide plan into action.

“It was so practical and I’d made sure it was definitely going to work,” he says.

“It was absolutely a-go and I didn’t even feel that bad about it because there was a sense of calm and relief that dying would let me move on in some way. I felt I was just taking up space.

“But then, it was like this inner Michael popped up. He got out of the car and just stood there, next to the door. It felt like another person was there all of a sudden but I think it was something inside me that found a strength and said `you have to keep going’.”

From that moment, his life took a different course.

He committed to teaching himself to walk properly again without a limp, and a year later moved to Melbourne to seek work as a playwright. He’d always enjoyed writing poetry and stories, but wanted to explore dramatic writing.

Soon after he arrived, he met a woman he describes as the love of his life.

“I was at an event for the Melbourne Fringe Festival where one of my plays was showing and I saw this woman and thought, ‘How can I get to meet a woman like that?’ but she asked me what I was doing at the Fringe. I wrote a play for her in nine days — a monologue,” he says.

“Apart from having one or two days apart, we’ve been together ever since. We have two gorgeous kids.

“I couldn’t have even sensed that was in my future when I was in that car. The heart can see further than the mind.”

The 53-year-old from North Balwyn now has a theatre company with his wife, Rohana Hayes, called The Wolves Theatre Company, and Marooned, his acclaimed play about suicide, is being considered by the Australian Defence Force to be shown to its members.

It’s now touring regional Victoria and is one of nine plays Griffiths has written and produced.

As happy as he is now, he isn’t detached from his dark stage and owns it with courage while also knowing that his life is so different now.

“I remember the struggle of it and know that it made sense to me at the time,” he says.

“I remember the pain and isolation of it all because, once you lose your family, you’re really left abandoned and you’re in the gutter but I was very, very wrong.

“I”m so happy I survived. I enjoy being alive. You’re only here for a short time (but) there’s no need to rush it and even though you can’t always be happy, living is essentially about being alive, in every way.”

For help with emotional difficulties, contact Lifeline on 13 11 14 or lifeline.org.au

CAITLYN BARNSLEY

The mother whose life was lost is often in the thoughts of Caitlyn Barnsley, whose life was inadvertently saved because of her tragedy.

But never more so than now that Barnsley, 26, is pregnant with her first child, due in March.

“I feel terrible for her, as a mother, to have left her children here while also being incredibly grateful to have a chance of motherhood myself,” Barnsley says.

“I think of her a lot.”

The warmth Barnsley, a preschool assistant from Croydon, feels towards her organ donor is just part of the gratitude she feels for life in general because she has lived mostly being extremely unwell.

Diagnosed with a rare liver disease (known as biliary atresia) when she was six weeks old, Barnsley would not have survived without a liver transplant at the age of 19.

Surgery soon after diagnosis saw her through her schooling though she wasn’t well enough to complete secondary school, leaving when she was 16.

She suffered chronic fatigue that left her unable to study properly and by the time she was 19, the whites of her eyes were yellow, along with her skin, and she was sleeping 17 hours a day.

When she starting vomiting blood, her mother rushed her to the hospital, and she went into a coma for two weeks. She survived, and was placed on the organ donor list.

“I never felt like I couldn’t go on, apart from a few points when I came out of the coma, because I didn’t know anything different,” she says.

“Other people around me did because I was seriously unwell but I was always positive about the scenario. I had a very positive family upbringing so I didn’t have too much doubt though I’m sure everyone else did.”

She waited nine months until a donor liver became available. The surgery went well and she was discharged from hospital after eight days but returned 10 days later suffering a major rejection.

“Everyone seemed to be very worried at this point because it was a serious rejection but after a few days of steroids, everything cleared up and I was right to go home again, albeit with directions to take 24 tablets a day,” she says.

“The first 12 months were hard. I had a moonface from all the steroids but then all my liver function tests came back normal. The colour of my skin went back to normal and it’s amazing how quickly it all happened.”

With a healthy liver, the chance to work full-time and a new love for potato chips that she couldn’t stomach before the transplant, she found a new lease on life.

Her energy levels boosted so she could go out more with friends and she even became a gym junkie for a while, mainly because she had never had the chance to exercise as a child and adolescent.

She recently celebrated her seventh anniversary of the transplant but her greatest celebration is to know that she is carrying a healthy baby daughter with her partner of 10 years.

“Pretty much, I’ve only ever had one dream since I was 15 years old and that was to have a family,” she says.

“It’s really special that it’s been able to happen. It never would have happened if someone didn’t give me the gift of life, which has made me a much more grateful person. If things don’t go to plan in my life now, I think `I’m still here and that’s what matters’.”

READ MORE:

HOW FRANCESCA CUMANI RUNS HER OWN RACE