The artist is not amused. Why MC Escher gave Mick Jagger no satisfaction

AFTER being largely ignored by art historians, M.C. Escher’s playful perspectives and head-scratching designs that could never exist in reality are finally making their mark.

Best of Melbourne

Don't miss out on the headlines from Best of Melbourne. Followed categories will be added to My News.

MATHEMATICIANS pored over his art. Hippies of the ’60s swooned, too, despite — or perhaps because of — their drug haze. And rocker Mick Jagger and filmmaker Stanley Kubrick could be counted as super fans.

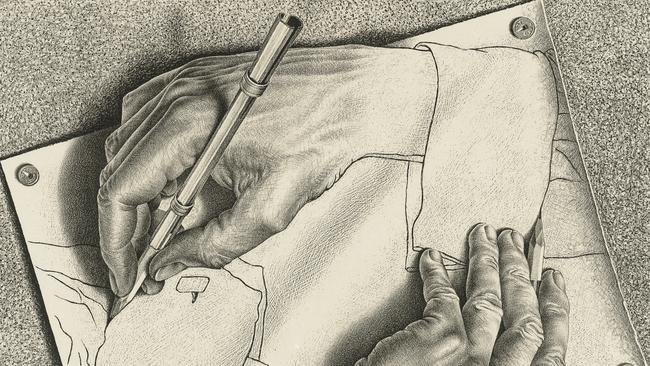

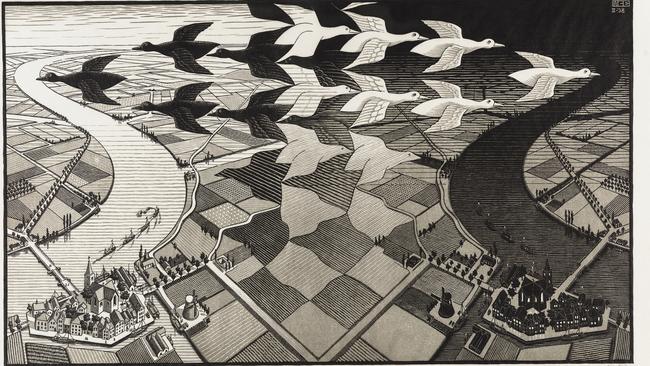

The mind-bending, boundary-pushing work of Dutch graphic artist Maurits Cornelis (M.C.) Escher has long intrigued, and while you might not know the name, his images of staircases to nowhere, hands drawing each other, water flowing upstream and interlocking reptiles and birds are some of the 21st century’s most famous.

About 160 of Escher’s prints and drawings are en route to Melbourne from The Hague’s Gemeentemuseum for the National Gallery of Victoria’s summer blockbuster Escher x nendo: Between Two Worlds.

SANDRINGHAM’S NEW PORT OF CALL CAFE HAS BEACHY VIBES IN SPADES

MITCHELL HARRIS WINE BAR THE BEST THING TO HAVE STRUCK BALLARAT SINCE GOLD

From Escher’s 1916 portrait of his father to his final work, Snakes, in 1969, three years before his death at 73, the pieces will be presented across several immersive spaces designed by acclaimed Japanese design studio nendo.

Opening next month, the exhibition marks several firsts — the first major exhibition of Escher’s art in Australia, the first time his artwork has been themed in an exhibition, and the first time nendo has designed an exhibition of pieces other than its own.

NGV director Tony Ellwood had the idea of pairing Escher’s work with a prominent design practice in early 2017 and invited nendo to take on the collaboration after seeing symmetry in their work.

“Like Escher, Oki Sato, the principal designer and founder of nendo, is a skilled storyteller fascinated with spatial distortions and shifting perspectives, and introduces a wonderful sense of playfulness in his design that parallels Escher’s use of humour and paradoxical visual devices in his work,” says the NGV’s senior curator of contemporary design and architecture Ewan McEoin.

“Other synergies between the two include their extraordinary imaginative prowess and their shared ability to create new and fantastic worlds, as well as their super-refined and meticulous approach to the execution of work.”

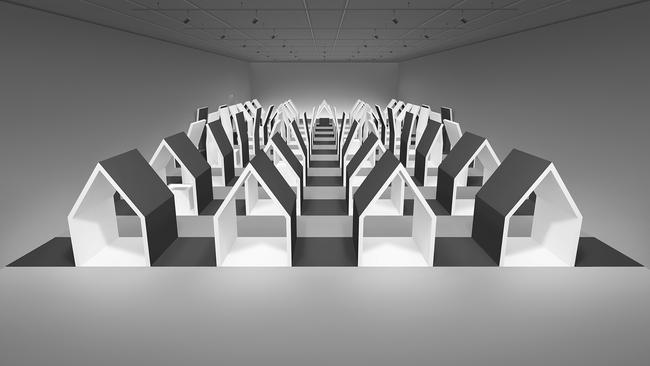

Sato admits he was slower to see the connection, and hoped for some kind of “chemical reaction” before landing on the exhibition’s signature motif, the minimalist form of a house.

“One thing we didn’t want was to use birds, fish, reptiles — Escher’s icons,” Sato says.

“Since there are more than 150 pieces, we needed a main character in the exhibition which would guide us through the different concepts and stories.

“When I look at Escher’s work, sometimes I notice there are strange insects or small people walking on stairs, so we thought this house … becomes like an icon of the space itself. This was like the small guide that tours us through.”

The house emblem is presented in many forms, materials, positions and functions across the mini galleries nendo has created that group Escher’s art in themes, including infinity and mirror images.

The main room will contain “a small village of houses” — 30-something 3m-high metal structures you can walk in and around. Some will have hidden displays containing an artwork. Viewed from different angles, the room will play with space and perception to create an immersive experience not unlike being in an Escher work. Other installations and an entrancing wall projection elsewhere in the exhibition will have a similar effect.

The final room, accessed by a serpentine corridor, will contain just two pieces — Escher’s Snakes, an intricate, painstakingly made coloured woodcut of three snakes lacing a disc of interlocking circles, and a sketch of the artwork before Escher transferred it to a wood block.

“That sketch is important because it’s about exploring within Escher’s mind and sharing the process,” Sato says.

Nendo senior designer Hadar Gorelik says that while the NGV brief was to “pump up the volume”, the studio was still mindful of “respecting the artwork but not too much —

in a positive way”.

“We try and break the rules — looking at things from upside down, from behind — but that wasn’t an option, so we needed to think about the right way to do that,” Gorelik says.

Nendo hopes to elicit an emotional response to their own designs as well as Escher’s.

“When you go to exhibitions, there’s just paintings and things that are two-dimensional and often you really don’t feel the experience,” Gorelik says. “It’s the first time Escher’s works have been presented in different angles and elements, intertwined with installations, so people will get many, many layers of experience, almost like stepping into an Escher artwork.”

Sato adds: “This is not just an exhibition for Escher fans. It’s also for small kids and people who aren’t interested in art. Maybe it’s a starting point for them.”

BENNO Tempel, director of the Gemeentemuseum, agrees that Escher’s optical illusions have broad appeal.

“(People) might not know the name but I’m sure everybody has been in a classroom some time where there was an Escher print in the maths or science room,” Tempel says.

“It’s funny to realise that the eye has been tricked. You start seeing the impossible.

“It’s great to go with family and children. Escher’s artwork is accessible on so many levels.”

With one of the world’s largest Escher collections, the Gemeentemuseum has loaned works for three major exhibitions in Scotland, Italy and Brazil since 2010. All were hugely popular, while The Hague’s dedicated Escher museum, Escher in Het Paleis (Escher in the Palace), opened a decade ago with 70,000 visitors a year, a figure that has now grown to 160,000.

Tempel says a new generation not so hung up on 20th century art movements such as cubism and surrealism is to thank for Escher’s growing popularity outside his native Netherlands.

“Because of these movements, everybody wants to have Picasso. ‘He’s the father of cubism, let’s have him’,” Tempel says. “And if, like the case of Escher, you didn’t fit into one of these movements, you fell out of art history. But in the 21st century, after all the movements have died out, there’s time again to look at artists and their individual qualities.”

And the fact Escher’s prints are made from woodcuts or lithographs make them even more impressive.

“So the process is that you draw an image on wood, cut away part of it so it gets the ink only on top,” Tempel says. “He was doing everything in reverse, so it’s a double trick. Also any words were a mirror image. It’s extraordinary.”

Day and Night was Escher’s most popular print, and he made more than 650 copies of it — using a small spoon made of bone to help dispense the ink on the woodblock to the paper.

“He had such a love for printmaking, which is often overlooked,” Tempel says. “He loved working with woodblocks to make the prints.

“If you make a painting, you put a brushstroke on the canvas. You can see what it looks like, and you put another one next to it. But with printmaking, you make a drawing and cut away and put a piece of paper on it and cross your fingers it works out.

“Sometimes printmaking is called the most democratic artwork because you can reproduce it and easily share it.

“Paintings are very bourgeois and elitist in that you have one painting and it’s a one-off and people can pay a lot of money for it and it’s theirs to hide away if they like and nobody can see it, but printmaking, everybody gets one.”

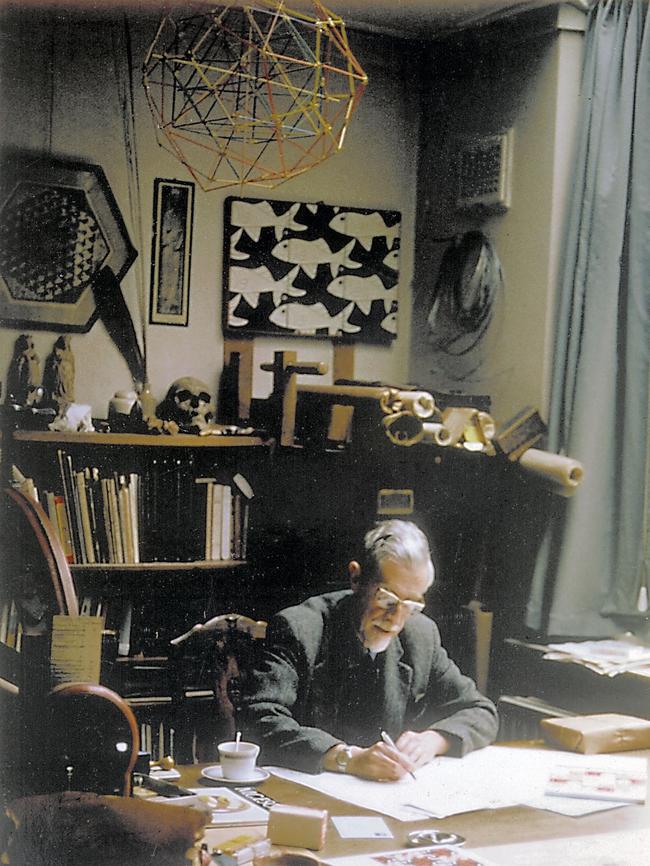

By all accounts, Escher was a generous man who gave prints to family, friends and neighbours. He was born in 1898 in the Netherlands to a well-to-do family that savoured art, music and theatre.

Escher loved to travel, which informed much of his work. Living in Italy in his 20s and 30s, the country’s hills and steeped villages gave his landscapes different points of view, while travels to Spain’s Alhambra palace with its geometrically precise interlocking mosaicsand patterned Moorish tiles inspired his now-famous tessellations, images that repeat within a pattern.

Among his greatest admirers were mathematicians who saw his work as an extraordinary visualisation of mathematical principles — impressive given Escher wasn’t a strong student in maths and his understanding was more visual and intuitive.

A mural of the foyer of his old school at Escher in Het Paleis showing a set of stairs not dissimilar to the gravity-defying staircases in Relativity perhaps gives an early glimpse of a student daydreaming about his future.

The conservative Dutchman also found himself the reluctant poster boy for the psychedelic generation of the ’60s that revelled in his dreamscapes and distorted designs.

In 1969, Jagger wrote to him asking permission to use a print for a Rolling Stones album cover, but was turned down. It’s said Escher probably didn’t know who Jagger was (he was more a Bach fan), but was also miffed to have been informally addressed by his first name.

“By the way, please tell Mr Jagger I am not Maurits to him,” was the rebuff.

Three years earlier, Escher spurned Kubrick’s request to collaborate on a “fourth-dimensional film”, speculated to have been 2001: A Space Odyssey, released in 1968.

But it doesn’t mean Escher was humourless, Tempel insists.

“He’s perhaps not the guy who slaps you on the back and says, ‘Let’s have another beer’, but he had a beautiful sense of humour — just a little bit ironic.”

ESCHER X NENDO: BETWEEN TWO WORLDS, NGV INTERNATIONAL, DECEMBER 2-APRIL 7. NGV.VIC.GOV.AU

MEGAN MILLER TRAVELLED TO THE HAGUE AND TOKYO COURTESY OF THE NGV

MEET OKI SATO, THE JAPANESE DESIGN FORCE BEHIND THE NGV SUMMER BLOCKBUSTER

FOR someone who’s collaborated with luxury fashion labels such as Tod’s, Louis Vuitton and Hermes, designing a fishing trawlermight seem a bizarre next move.

But for Oki Sato, founder of Japanese design house nendo, no medium or project

is off limits. It’s this versatility that’s helped make him — at 40 — one of the world’s

most prolific designers.

After graduating with a masters degree in architecture from Tokyo’s Waseda University, Sato launched nendo — the name referencesmodelling clay or children’s Play-Doh in Japanese — in his parents’ garage in 2002.

He’s worked with some of the biggest names in furniture, fashion and luxury goods on everything from chocolates and shoes to perfume bottles, chess sets, store interiors and private homes. He’s also designed a studio set for a Japanese TV station, bird houses for a Japanese wildlife sanctuary, and recently published a quirky picture book for kids about problem-solvingand how ideas are formed.

Known for their clean lines and witty, playful touches, nendo designs can be found in the Museum of Modern Art in New York, Paris’ Centre Pompidou and Melbourne’s own NGV International, where his 50 cartoon-inspired chairs for last year’s Triennial exhibition remain in the permanent collection.

Based in Tokyo, nendo employs about 30 designers, helmed by Israeli-born Hadar Gorelik, but that number swells to about 80with management staff and collaborators.

The company has grown so much it’s about to take over a third floor of its swanky office tower overlooking the parklands of the Akasaka Imperial Palace in Tokyo’s commercial district. It also has an office in Milan, Italy.

With up to 300 projects on the go at any one time and a 10-minute daily radio spot on design, Sato deliberately keeps his world outside work simple. He wears the same black pants and white shirt every day, has the same breakfast and noodle lunch, and lives “30 seconds from the office” in a basic apartment he shares with his chihuahua-pug cross Kinako. He takes comfortin the routine.

“In this life, there’s a limited number of good decisions and I want keep them for design, not choosing my underwear,” hesays. “Not having to think about anything is a way of relaxing, I guess.

“Even when I travel, I stay in the same hotel and eat the same salad and try to stay the same. It’s a way of staying flexibleto each of the projects, too.”

In July, nendo won an international competition to design the interiors of France’s next generation of high-speed TGV trainsbefore the 2024 Paris Olympics.

Other projects include designing a ramen fork, helping a Japanese bank attract younger customers by creating an electroniccharm that carries banking info, and that trawler.

“There are 15 guys living there for six months, so it’s like designing a residential space,” Sato says. “There will be stressobviously staying in the same space for six months with the same people, so that’s a challenge, but I feel the boundaries and possibilities of design are expanding.”

Sato clearly enjoys working on such a diverse range of projects.

“I’m a workaholic but I don’t feel like one,” he says. “It’s like playing video games all night — yes, you get exhausted butyou love it. I don’t have any hobbies. A crazy client comes along and you don’t know anything about your future.”

RELATED CONTENT