‘I was told there was no hope for her’: Jonathan Brown opens up about losing his mum

When Jonathan Brown arrived at the hospital after his mum Mary fell ill, he was told there was little chance she would survive – and he had to make a life-changing decision.

Lifestyle

Don't miss out on the headlines from Lifestyle. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Jonathan Brown considers his beloved mum, Mary’s final act of becoming an organ donor a “reflection of her selflessness”.

Fellow former AFL captain Phil Davis says the same of the best mate he lost suddenly when they were both just 18, Jack.

Their loved ones saved several lives and transformed many others in a way only a small portion of people can each year.

Just 2 per cent of those who die in Australian hospitals meet the criteria required to be an organ donor. In 2022, 1400 people were in this category.

After their families were asked for consent and their eligibility was assessed, 454 organ donors were left to help 1224 transplant recipients.

Meanwhile, more than 1800 Australians are on the waiting list for an immediate organ transplant.

Geelong star Patrick Dangerfield’s close friend, Aaron Habgood, isn’t quite in this category. But the heart Habgood received from a donor 15 years ago will need to be replaced at some point.

“It could be a week with this heart, it could be another five years,” the father of two says. Dangerfield adds: “It’s a big shadow to have hanging over you, knowing at some stage your heart will need replacing. I couldn’t image what it’s like, but he handles it extraordinarily well.”

Ahead of DonateLife Week, from July 23-30, Brown, Davis and Dangerfield have banded together to encourage Australians to take the one minute required to register as organ and tissue donors, and then let their families know their wishes.

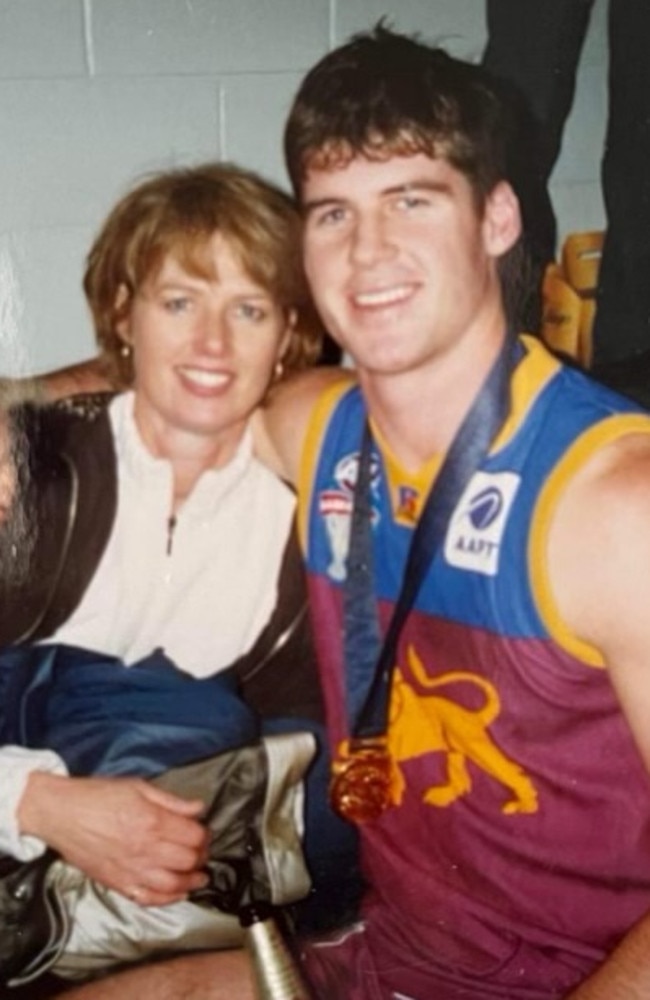

Jonathan Brown

Jonathan Brown is both proud of and startled by the fact his beloved mum, Mary, was one of just 454 Australians who became organ donors last year.

Mary’s gifts were lifesaving for two people and life-changing for several others. This provided “a pretty strong level of comfort” to Brown and his family in the wake of her sudden death from a brain haemorrhage at age 62.

“It’s a reflection of her selflessness. You couldn’t typify her any more than (the fact) she was able to give ongoing life,” the AFL great says.

“But the stats were confronting. There are so few of Mum every year, that means there are so many out there who need support for ongoing life who don’t get it and pass away prematurely.

“It’s confronting how little organ donation we have.”

Brown, father Brian and siblings Matthew, Timothy and Gabrielle didn’t hesitate in saying “yes” to Mary’s organs and tissue being transplanted when asked by staff at Melbourne’s Monash Hospital.

The Brisbane triple-premiership player says he knew his mum’s wishes from a young age – he recalls asking Mary, “how come you’ve got that sticker on your licence?”, and her responding, “I’m an organ donor”.

Brown, his wife, Kylie, and brother Timothy were the first to arrive at the Monash after Mary was airlifted there from the home she shared with Brian in Koroit, in western Victoria, last September.

“I was told within an hour of getting to the hospital … that there was no hope for her,” the 41 year old recalls.

“(After that), the staff are conscious of trying not to be unemotional, but they have to go through the process – she’s registered as a donor but they have to (get your consent). We knew what her beliefs were, so we obviously said yes.”

Mary was kept on life support to allow the transplant team to extract her organs.

“One of the benefits for us, in hindsight, was we got to spend two to three days with her, say our goodbyes,” Brown says. “(Kylie and I) wrestled with the decision to take our kids in there, but I’m glad we did.

“It was an emotional time, but we were able to say goodbye and hold her hands.

“Without having to wait for the transplant team, we wouldn’t have had that opportunity.”

Brown admits he was “nervous” about seeing his mum after her organs and eye tissue were extracted. But he says after Kylie, a beauty therapist, made up her for he funeral, “you wouldn’t even know” from looking at her.

He also says Mary’s donation experience will “give me that little jolt” to take the 60 seconds required to register as an organ and tissue donor.

“I’m a reflection of most of society – we get too busy, other things take priority in our lives and we forget to do it,” he says.

About 10 months on, Brown remembers Mary as an “incredibly caring” person who put others first “almost to a fault”, despite having health challenges throughout her life.

She was beloved “Nanna Mary” to Brown’s kids, Olivia, Jack and Macy, and would have been the same to his niece who was born a week after her funeral. Brown’s sister, Gabrielle, named her Emily Mary in their mum’s honour.

“What stood out was her generosity and heart,” Brown says. “She was a nurse, so that probably shows what her personality was like.

“Mum was the taxi driver all over Victoria when I was playing footy. Without that, I wouldn’t have had a career and a life around football.

“She was beautiful lady.”

Phil Davis

Abruptly losing his close mate, Jack Klemich, to meningococcal disease at age 18 was “hard to comprehend” for Phil Davis.

“It was 2009, we’d gone out and had a few drinks at a mutual friend’s house on the Saturday night,” the GWS footballer recalls. “Then, we got a call the Sunday evening saying he wasn’t very well and by Monday afternoon, he had basically become brain dead.

“It was such an enormous loss at such a young age. These days, I have some perspective on what his parents and sisters have gone through.”

This includes enormous respect for how the “incredibly selfless” Klemich family has used “a terrible ordeal in their lives to help others”.

Jack was registered as an organ donor, and his gifts went on to transform five lives. His father, Oren, has also become a powerful advocate for meningococcal research and the promotion of organ donation, as a member of the Organ and Tissue Authority advisory board.

“Oren is one of the great people I know,” Davis says.

“And my lasting memory of Jack will always be that he was such a kind and giving guy. We never spoke about it (organ donation). But he was always so into helping others.”

Davis met Jack at age 13 shortly after moving to Adelaide and starting at St Peter’s College. The pair played cricket together within Davis’s first week at the school and became fast friends.

“He was very welcoming and warm, and made a lot of effort to make sure I fit in at the school he had a lot of friends at,” the 32-year-old says.

“He was just a genuinely nice guy, never said a bad word about anyone. A quiet, shy sort of guy but he could be as cheeky as anyone as well.

“We played cricket and football all through school, he was always having people over to his house – his parents, Oren and Gill, and sisters were always very hospitable.”

A 2007 cricket trip to England together is particularly memorable for Davis. Two years later, Jack was suddenly gone.

Davis has been familiar with the topic of organ donation from a young age. “My mother’s a doctor, she’s always talked about it,” he says.

“It’s been in our values as a family, that we would donate organs. Mum’s seen the impact it can have at the other end and understands the amazing difference it can make.”

But Jack’s situation and his father’s involvement with DonateLife have made him a passionate advocate.

“I make sure whenever it comes up in conversation that people are registered the right way, if that’s their intention, so if something were to happen, they would be able to donate,” he says.

“I’m really proud of Jack. He’s been able to have a lasting effect beyond what he was able to do in his 18 years by helping other families avoid the loss of a loved one.”

Patrick Dangerfield

Aaron Habgood’s passion and gratitude for life quickly became evident to Patrick Dangerfield after the pair met on a boat ramp in Victoria in 2015.

Learning later that Habgood had a lifesaving heart transplant at age 16 gave the Geelong champion some perspective on this outlook.

“It’s pretty extraordinary, having had that sort of operation and to be in the health he’s in now,” Dangerfield says of Habgood, now his close mate and co-host on radio fishing show Reel Adventures.

“He’s very grateful for his opportunity at life. He wouldn’t exist if it wasn’t for organ donation, that’s why he’s so passionate about it.

“He’s had setbacks over the years, but he lives life to the fullest.”

After about a year of experiencing dizzy spells, Habgood was diagnosed with aortic stenosis at age 16, leading to him needing open-heart surgery. The procedure was successful, but 24 hours later, he experienced a cardiac arrest.

“I was dead for half an hour, defibbed eight times, but they got me back,” he recalls.

“A short time later, I went back into cardiac arrest. This time it was much worse. The surgeon hand-pumped my heart for half an hour while they hooked me up to life support, then I received my transplant.

“I’d be dead (without the transplant). All my other organs were slowly going into failure.”

Now aged 31, happily with partner of 10 years Kari and father to Finn, 3, and Mia, 1, Habgood is in decent health. But he lives with the knowledge he will need a new heart in the coming years.

He thought that time had come last year, when a patch of poor health landed him on the waitlist for a transplant and in a dark headspace.

“My kids growing up without a dad was a nasty thought that went through my head, but it was also pretty realistic (at the time),” he says. “Some days, I couldn’t tie shoes or hold the kids in the shower.

“I had more than 30 procedures in 12 months, multiple ambulance trips from home, spent a lot of weeks in hospital.

“But the transplant team worked with me to ensure my heart didn’t have to work as hard to push fluid around my body. I turned a massive corner about four months ago, my heart function has come up. I’m absolutely flying compared to where I was.

“I’m nearly 15 years transplanted, I want to get to 20.”

He’s aiming to achieve this by monitoring his fluid intake and weight, and taking medication.

Habgood is grateful to his family, and mates like Dangerfield and fellow Geelong star Gary Rohan for supporting him through his tough patches.

“Gary even came over to my place when I was in hospital one time and cleaned my whole house,” he says.

The one person he would love to thank, but can’t, is his donor. “I’d love to tell them the life I’ve given this heart,” he says.

Dangerfield is awed by how his mate will “have a crack at absolutely anything”, from playing footy and cricket, to diving and “driving 80km offshore chasing southern blue fin tuna in 6m swells”.

The Brownlow medallist is a proud registered organ and tissue donor. He urges Australians to educate themselves on the topic, with an open mind towards signing up too.

“My uncle, Tim, was killed in car accident in 1996. I was six at the time, and my grandma … made the decision to donate Tim’s organs,” Dangerfield says. “It’s always been clear to me, from growing up, if you have the chance to help someone else, you do it.”

More Coverage

Originally published as ‘I was told there was no hope for her’: Jonathan Brown opens up about losing his mum