Australia’s organ transplant waitlist reflects urgent need for registered donors

More than 1800 Aussies are waitlisted for a lifesaving or life-changing transplant, from a baby who needs a new liver to a young dad awaiting a third kidney donor. Read their stories.

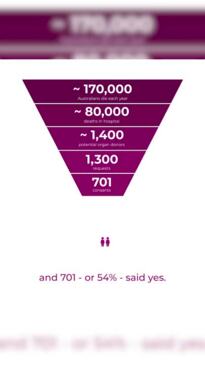

Australia’s organ transplant waitlist peaked at almost 1900 patients this year – but many more could significantly benefit from a transplant if the nation had a higher number of suitable donors.

This includes many of the 14,000 people with kidney failure who are on dialysis, Organ and Tissue Authority (OTA) national medical director Helen Opdam says.

One in five Australians waitlisted for an immediate transplant are aged below 40, while men on the list significantly over-represent women, OrganMatch figures released ahead of DonateLife Week reveal.

The aim of DonateLife Week, from July 23-30, is to encourage Australians aged 16-plus to register as organ and tissue donors and then tell their families they want to become donors. One donor can save up to seven lives.

“It’s quicker and easier than ever to register – it takes just a minute at donatelife.gov.au or three taps in your Medicare app,” OTA chief executive Lucinda Barry said.

“You’ll be giving hope to Australians on the organ transplant waitlist. For them, it can be a matter of life and death.”

Associate Professor Opdam, also a senior intensive care specialist at Melbourne’s Austin Hospital, said more dialysis patients could also gain the opportunity to be transplanted if more donor kidneys were available.

“People on dialysis are often fatigued, foggy headed, have no appetite or energy,” she said. “Dialysis is needed three or more times a week, several hours at a time, which is very constraining.

“A transplant could give people their energy back, and it’s much more cost effective on the health system than dialysis. But there’s no point putting thousands of people on the waitlist for a kidney when they’re not going to receive one.”

On top of adding more Australians to the Organ Donor Register, Prof Opdam said expanding the nation’s transplant practices and capabilities was crucial to helping more people with organ failure.

She is hopeful a new national strategy for transplantation, currently being developed by the federal, state and territory governments, could achieve this.

“Only 1400 people die each year in circumstances where they can become a donor,” she said, noting family consent was then required for donation to occur.

“If we expand our practices in the same way as Spain – a world leader in organ donation – by building capacity and improving technology in transplant units … we could have a larger number of people who could become donors.”

This could include older donors – 57 per cent of donors in Spain are aged above 60 compared to 30 per cent in Australia, according to Prof Opdam.

Australia’s waitlist rose to 1891 patients in April. The most recent OrganMatch figures have 1823 people on the list, with 1432 needing a new kidney.

More than 300 require a lifesaving heart, lung or liver. Prof Opdam said people in this situation often spoke of feeling “like they’re trapped in a tunnel with no way out”.

“A transplant is that light at the end of the tunnel,” she said.

The 50-59 age group has the highest number of waitlisted people, with more than 500. But younger Australians are also in urgent need of transplants, with 32 people aged below 18, 87 from 19-29 and 221 from 30-39 also on the list.

There are almost 400 more men than women on the list, with the gender gap increasing in the older age groups.

To be waitlisted, patients must pass a “workup” – comprehensive medical testing to ensure the transplant has the greatest chance of success.

An algorithm then finds organ matches, taking into account the urgency of the transplant, how difficult a patient is to find a match for, how good a match the organ is for the patient, and how long a person has been waiting.

In 2022, 1224 Australians received organs from 454 generous donors.

“Each of us, in our lifetime, is more likely to develop organ failure and need a transplant than we are to die in circumstances where we could be a donor,” Prof Opdam said. “It’s quite rare.”

Brave Thea beating the odds while on transplant waitlist

Mia and Brett Fulgencio know not to underestimate their little girl, Thea.

Despite being one of the youngest Australians on the waitlist for an organ transplant, the two-year-old is proving the experts wrong.

Thea was born premature in May 2021 with an abdominal cyst and biliary atresia, a condition where the bile ducts in the liver are blocked.

She had the cyst removed at two days old and at two months, she underwent a kasai procedure in which her gut was connected straight to her liver.

Thea still receives nutrition through a drip line and a feeding tube. But after 324 days at Adelaide’s Women’s and Children’s Hospital – including two Christmases and her first birthday – she finally went home with her parents to wait for a new liver to be found for her.

“We were told Thea wouldn’t walk until she had a transplant, but she’s walking already,” Ms Fulgencio said.

“We were told most children with her condition don’t eat orally, but Thea loves eating, especially porridge and chocolate. We are amazed every single day by the things she can do.”

Thea has been on the waitlist for a year now.

She came agonisingly close to receiving her transplant earlier this year, with her parents receiving a call on Good Friday that a liver match had been found.

The family raced to Melbourne’s Royal Children’s Hospital for the operation. But at the last minute, the liver was deemed unsuitable and surgery was cancelled.

The ‘dummy run’ left the family traumatised, particularly since public holiday staff shortages meant nobody explained why the operation had been cancelled.

“As we wait, our life is so unpredictable, it’s like our lives are on hold, it’s really tough, especially on my 11-year-old son, William,” Ms Fulgencio said.

“Our hope is that Thea will be able to enjoy as normal a life as possible one day.”

Young dad awaits third transplant to combat ‘silent killer’

When Evan Groves learned his kidneys were failing, seemingly out of nowhere at the age of 32, his mum selflessly offered to donate one of hers.

Mr Groves was beyond grateful for Leanne’s gift. But complications arose and seven days later, he lost the transplant.

“I was devastated my mum went through so much for it not to work out,” he said.

The Coburg man had been diagnosed with IgA nephropathy in 2018, after developing headaches, nosebleeds and blurry vision in one eye while on holidays in New York with his young son, Jensen.

“Before that, I was fit and healthy and never really thought about going to the doctors,” said Mr Groves, now aged 37.

“All of a sudden, my kidneys were failing.”

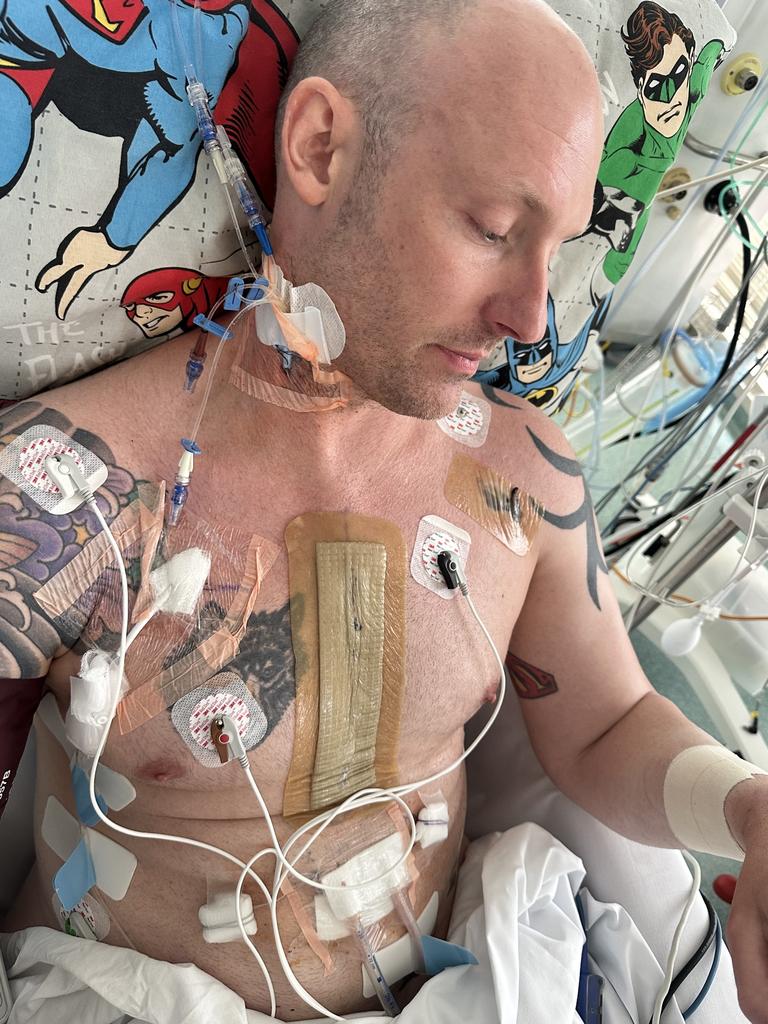

Mr Groves started dialysis and joined the organ transplant waitlist after his body rejected the kidney. About 18 months ago, he received a call while shopping at Northland that a match had been found for him via a deceased donor.

“It went pretty well at first,” he said. “But I was doing routine blood tests, and one in January this year showed rejection was starting to happen.

“After trying to save the kidney, it was fully rejected in March and they had to take it out.”

As Mr Groves waits for a third donor, he undergoes haemodialysis three times a week, for six hours at a time. The treatment sees “a big needle suck out my blood, clean it and put it back in”.

Being on dialysis limits Mr Groves to a litre of fluid intake a day and restricts his movements, among other limitations. A transplant would be “life-changing”.

“It would mean I could see my son and my family more often, and when I’m there with them, I’m healthier and more available,” he said.

“After my second transplant, I used to think about the donor all the time and thank them in my head. It’s such a generous gift.”

He urged all Australians aged 16-plus to consider registering as organ donors. Anyone with a family history of kidney failure or high blood pressure should also speak to their GP.

“They call it the ‘silent killer’,” he said. “I wouldn’t wish it on anyone.”

Heart transplant lifesaving for fit father of two

Rob Hodgson remembers exactly where he was when he received the call.

It was 1am on October 16, 2021 and he was woken from sleep to hear the words, “I think we’ve found a good match”.

Within hours, Mr Hodgson was at hospital and being prepped for surgery that would replace his damaged heart with a fully functioning one.

In the lead up to this moment, he had sat on the organ donor waiting list for almost a year, too scared to even leave his house for fear his heart would give out as it had threatened to so many times.

The Sydney father of two was doing interval raining in his garage the first time his heart gave out, in November 2020. He felt suddenly dizzy, his heart was racing and he felt like he was going to pass out.

Later that night, he had another episode when he went to stand up from the couch. Tests later revealed he had dilated cardiomyopathy, where the heart becomes enlarged and cannot pump blood around the body effectively.

With no history of heart disease in the family and elite level fitness, it was concluded the Covid Mr Hodgson had contracted eight months earlier had weakened his heart.

An internal defibrillator that shocks his heart when its function becomes dangerously abnormal was installed. This occurred several times over the next few months, including one episode where it was shocked more than 30 times in a row.

“I was saying to the ambos, ‘don’t let me die’,” Mr Hodgson said of that night.

“After I left hospital, I was scared to even move. I didn’t leave the house. I was scared I would die every single day.”

He has since returned to his job as a clinical prosthetist and started riding his bike again, to the delight of his wife, Amanda, and kids Lukin, 11, and Arlo, 9.

“I think about whose heart I have beating in my chest every single day,” Mr Hodgson said. “I wonder what that person was like.

“Because of the transplant, my sons still have their dad.”

‘Really tough’: two years in limbo waiting for transplants

Jenny Kosten tries not to think about the call that could save her life.

She has been waiting more than two years to her phone to ring with the news a donor match has been found for her double heart and lung transplant.

The 43-year-old has had to move from her home town of Bundaberg to Brisbane to be closer to Prince Charles Hospital for when the call comes. She has had to give up her job while she waits, and can no longer enjoy her love of nature photography, as walking leaves her light headed and short of breath.

“I try not to think about it too much,” Ms Kosten said. “It’s daunting because it can happen at any time and I have to be ready.”

Ms Kosten was born with six congenital heart defects, leading to a childhood spent in and out of hospital.

She resisted joining the waitlist for a transplant in 2016 as she wasn’t feeling so bad then. But by May 2021, she relented as her health deteriorated.

Ms Kosten is also being monitored for a possible liver transplant as that organ has deteriorated, too.

Before she moved, she was travelling to Brisbane, sometimes weekly, to have a fluid build up removed from her heart. This added to Ms Kosten and husband Lawrence’s decision to quit their jobs and head south.

“The decision to move was really tough,” she said. “I had never wanted to make that move and leave behind all my family and friends, but the constant travel was taking a toll.”

Ms Kosten encourages everyone to register as a donor and help reduce the waitlist.

“By giving just one minute of your day, you can give a lifetime to someone like me,” she said. “But don’t just register, tell your family that you are a donor too so they know what your intentions are, that’s important.”

Kidney transplant hopeful on mission to ‘enjoy life’

It didn’t seem like a big deal when Yorke Mountford copped a small dog bite on his thumb.

The scratch didn’t even draw blood.

But within 24 hours, the Risdon Vale resident was in intensive care on life support.

“The name of the rare disease is capnocytophaga,” Mr Mountford said.

“The doctors didn’t know that at first and it did its worst, quickly.”

Mr Mountford had a compromised immune system after losing his spleen from a motorbike accident decades earlier, meaning he nearly died when the bacteria entered his blood via the dog bite in 2008.

“My body shut down systemically with no blood flow to extremities,” he said.

“My body shut down, organs shut down as well. My skin as well – it went black and wrinkled. I was in a coma for a lot of it.”

Mr Mountford battled his way through a severe case of sepsis, but had to undergo the amputation of both legs below the knee and all fingers and thumbs.

He’s lived to tell the story, but the former high-voltage linesman suffered permanent damage to his kidneys.

While he slowed the progression of his kidney failure with healthy eating and exercise, their function has slowed to the point he now requires dialysis three times a week.

Mr Mountford, who is on the waiting list for a kidney, has come forward to share his story ahead of DonateLife Week from July 23-30.

Mr Mountford encouraged people to speak with their loved ones and register on the DonateLife website.

“The more donors, the shorter the waitlist,” he said.

Meanwhile, Mr Mountford is making the best of every day while he waits for a new kidney.

The retired grandfather is a volunteer driving instructor who keeps fit, swims regularly, and even carried the baton for the Commonwealth Games in 2008.

He’s got a bucket list running, and hopes to one day swim with turtles on the Great Barrier Reef.

Mr Mountford is looking forward to the days when he’s no longer tethered to the dialysis machine and can go travelling and camping.

“I think the most important thing to do is enjoy the life we have,” he said. “I cram in a lot of life.”