‘Ripped off’: Kmart slammed for ‘un-Australian’ act

The retail giant has been accused of ripping off a small Australian business, known for making innovative kitchen tools.

Interiors

Don't miss out on the headlines from Interiors. Followed categories will be added to My News.

You can hear the pride in Alex Gransbury’s voice over the phone as he describes the Fluicer, his proudest invention.

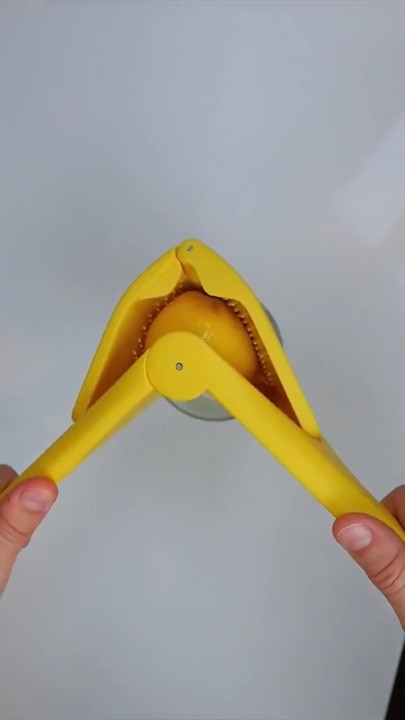

A handheld citrus juicer with a fold-flat design, the Fluicer is meant to mimic how you would naturally squeeze citrus with your hands by folding it, rather than squashing it, meaning you can extract significantly more juice.

Its bright yellow form is sleek, functional, and the culmination of 22 years of reinvention.

But now, the Fluicer is at the centre of an all-too-common situation for small businesses – one that sees Mr Gransbury, the founder of Dreamfarm, grappling with the reality of his design being allegedly copied by Australian retail giant Kmart.

For Mr Gransbury, the news that Kmart was selling what appeared to be a dupe of his award-winning design under their Anko brand was more than a professional insult, it was personal.

“It felt like the air had escaped from my lungs,” he recalls to news.com.au. “It was an absolute gut punch.”

The Kmart version, called the Folding Juicer, retails for just $5.

By comparison, the Fluicer, which is sold in three sizes to fit limes, lemons and oranges, ranges from $19.95 to $29.95, depending on the size.

While the Folding Juicer’s low price may appeal to budget-conscious consumers, Mr Gransbury says it lacks the quality and functionality that Dreamfarm painstakingly engineered into the original.

From a Brisbane garage to Oprah and Time Magazine

Dreamfarm’s journey began in 2003 in a humble garage when Mr Gransbury was just 22 and still at university, studying finance and accounting.

“I loved tinkering and coming up with ideas and I wanted to do something interesting with my life,” he says. “So, I took a product idea that had several concepts and decided to create one of them using parts I could buy from the local hardware store. I ended up making a coffee grinder and that weekend, I took it to the markets and sold it to a bloke from a local kitchenware store.”

Next came some pizza scissors and a potato masher, and before he knew it, he was known as the “kitchenware guy”.

Over the following two decades, Mr Gransbury and his team have built a reputation for revolutionising everyday kitchen tools, believing the kitchen is like “a workshop inside the home.”

Their products aim not for small improvements but for genuine innovation.

“Most designs focus on making incremental changes to existing products, adding just a 10 or 15 per cent improvement. For instance, a salad spinner might operate at 3000 RPM instead of 2000 RPM,” he explains.

The Fluicer is a prime example of his innovative approach to design and it quickly found international acclaim, including a spot on Oprah’s Favourite Things list and recognition as one of Time Magazine’s Best Inventions of 2023, the latter of which “marked a turning point” for the small business.

“Suddenly, the dads at the barbecues were starting to take notice of us. Before this, we were like inventors with crazy ideas that fans loved, but we weren’t a household name, and we certainly weren’t on the radar of big companies trying to copy us.

“For the first time in 22 years, people outside the design world started to notice.”

The Kmart discovery

However, with this sort of virality, sadly, often comes copycats.

On Tuesday, Mr Gransbury received the heartbreaking call from a team member about Kmart’s $5 Folding Juicer.

“I have three kids, ages 10, eight and five. When I got home, my eldest said he was so sorry to hear about what happened with Kmart and he started to cry,” he says. “It hit me hard.

“You know how much time, effort, and energy goes into designing these products. It feels like the wind has been taken out of my sails.

“Kmart, or any of these other copycat brands, don’t have to do any research and development – they just show up and steal someone else’s idea.

“What they don’t understand is that for every 60 products we’ve developed, there are hundreds of prototypes that didn’t work, that never made it off the ground.”

He references James Dyson, and the fact that he had to make 5127 prototypes before his first vacuum cleaner worked.

“I completely relate to that,” he says.

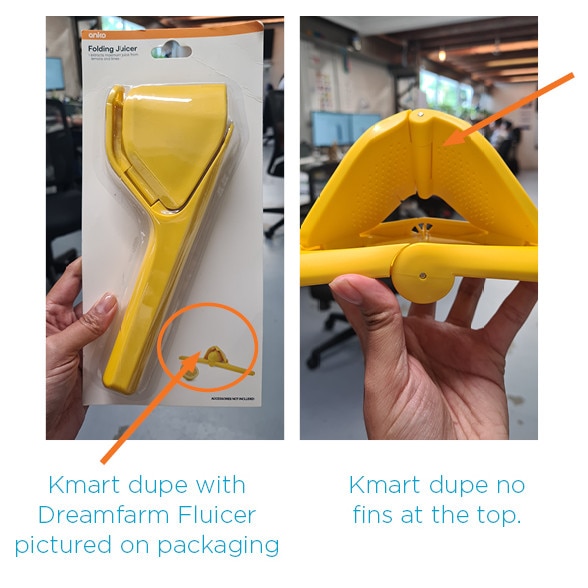

After rushing to Kmart to buy the knock-off version and dissect it, it became clear that Kmart had replicated Dreamfarm’s lime-sized Fluicer but coloured it yellow and marketed it as a lemon juicer.

What’s more, Kmart’s product packaging and website appeared to showcase features that mirrored the Fluicer’s design but were absent from the actual product.

“What the consumer sees on Kmart’s website and packaging is misleading,” Mr Gransbury explains. “But you wouldn’t know until you remove the packaging.”

To make matters worse, the $5 Folding Juicer’s reduced size renders it impractical for juicing lemons, a flaw that Mr Gransbury takes small comfort in.

“From our experience, you won’t be able to fit a lemon in the lime-sized version,” he says.

“It’s frustrating when someone blatantly rips off our work for commercial gain, especially when they don’t even attempt to improve upon it.”

A Kmart spokesperson told news.com.au: “Our merchandise team is focused on creating curated ranges that align back to global trends, enabling us to provide our customers with great products at the lowest possible price.

“Our merchandise process also ensures we conduct thorough checks during the product ranging and development process, to ensure we are not infringing the rights of others.”

The legal dilemma

“We’ve been copied many times,” Mr Gransbury admits. “There are always copycats. But this is the first time a major retailer in our own market has done it. That’s what stings the most.”

The Fluicer is patented in the US, where most customers are located, and the brand can seek triple damages if their product is ripped off there.

But it’s not patented in Australia due to the high costs, making it economically unviable.

“The best we can hope for is to recover the profits that someone else made from our product, but often they sell it at such low margins that the compensation is minimal,” he explains.

Plus, enforcing patents is a costly and time-consuming process.

“Even with a patent, you have to litigate,” Mr Gransbury says. “It can cost $5000 dollars to send a cease-and-desist letter to Kmart, which they can easily ignore.”

It’s a road he’s been down before. In one instance, he took legal action against a competitor who copied his potato masher, ironically after he had given the owner advice about patents at a trade show in Frankfurt.

While he won the case, the financial toll was devastating.

“I spent $30,000 to recoup $8000 in profits,” he says. “The lesson I learned is: for what? Why bother? That money could have been better spent on developing our next product, allowing me to innovate sooner.”

“I share this story to remind you, and myself, that imitation is often seen as flattery. If you are on the verge of changing how something is done, that’s inevitable. It’s important to accept that this validates your efforts and to move forward with your next project.”

For now, Mr Gransbury takes solace in the fact that Dreamfarm’s designs continue to set the standard for quality and innovation.

“Ultimately, those who truly value design will always be your customers. They want the latest innovations as soon as they are available, they won’t wait for cheap knock-offs.

“I hope that many people explore Dreamfarm to discover the exciting products we’ve created. There’s a wealth of Australian innovation out there, and we’re continuously working on the next great thing.”

Originally published as ‘Ripped off’: Kmart slammed for ‘un-Australian’ act